Advertisement

As literacy screening becomes a requirement in Mass., a look at what impact it makes in schools

Resume

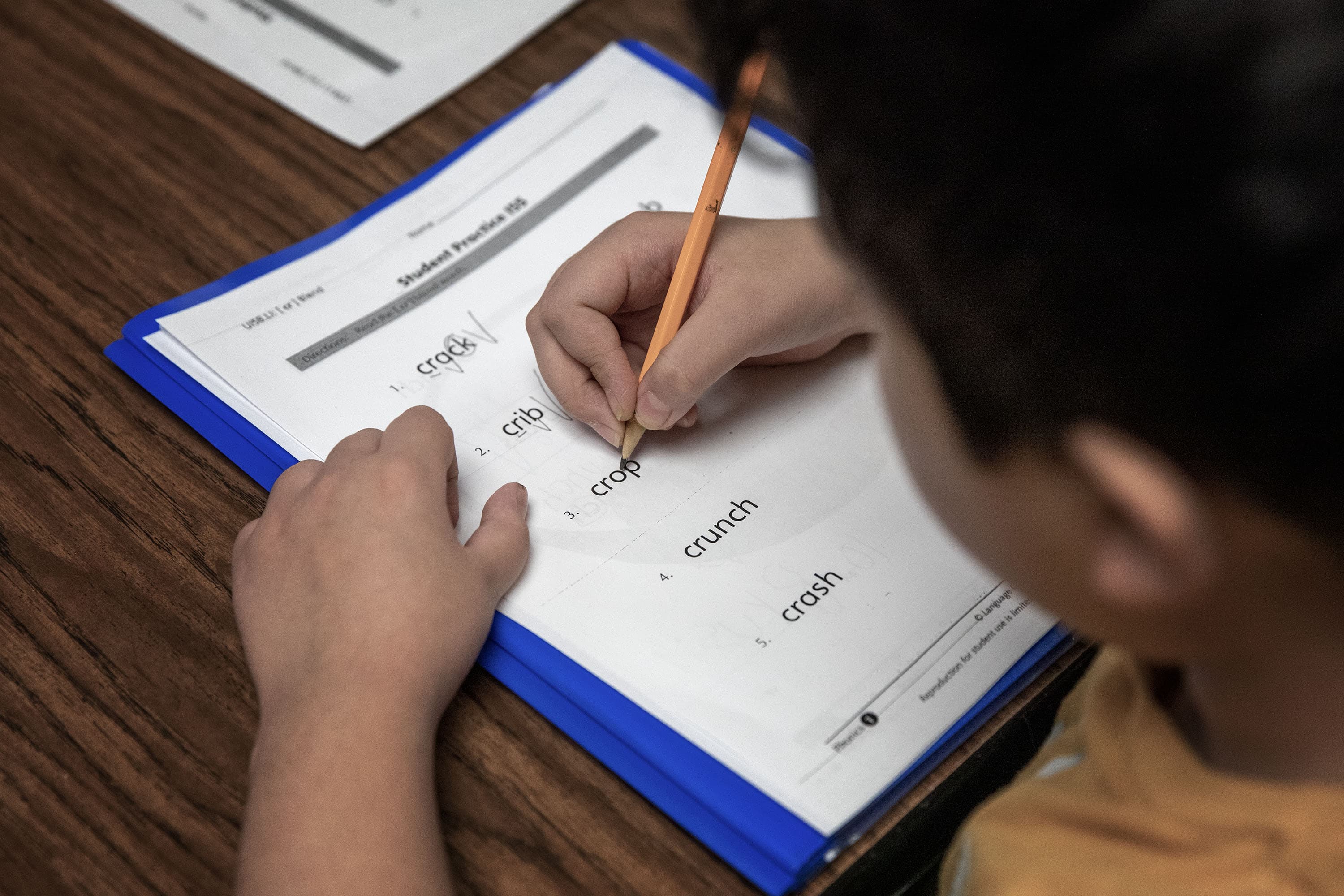

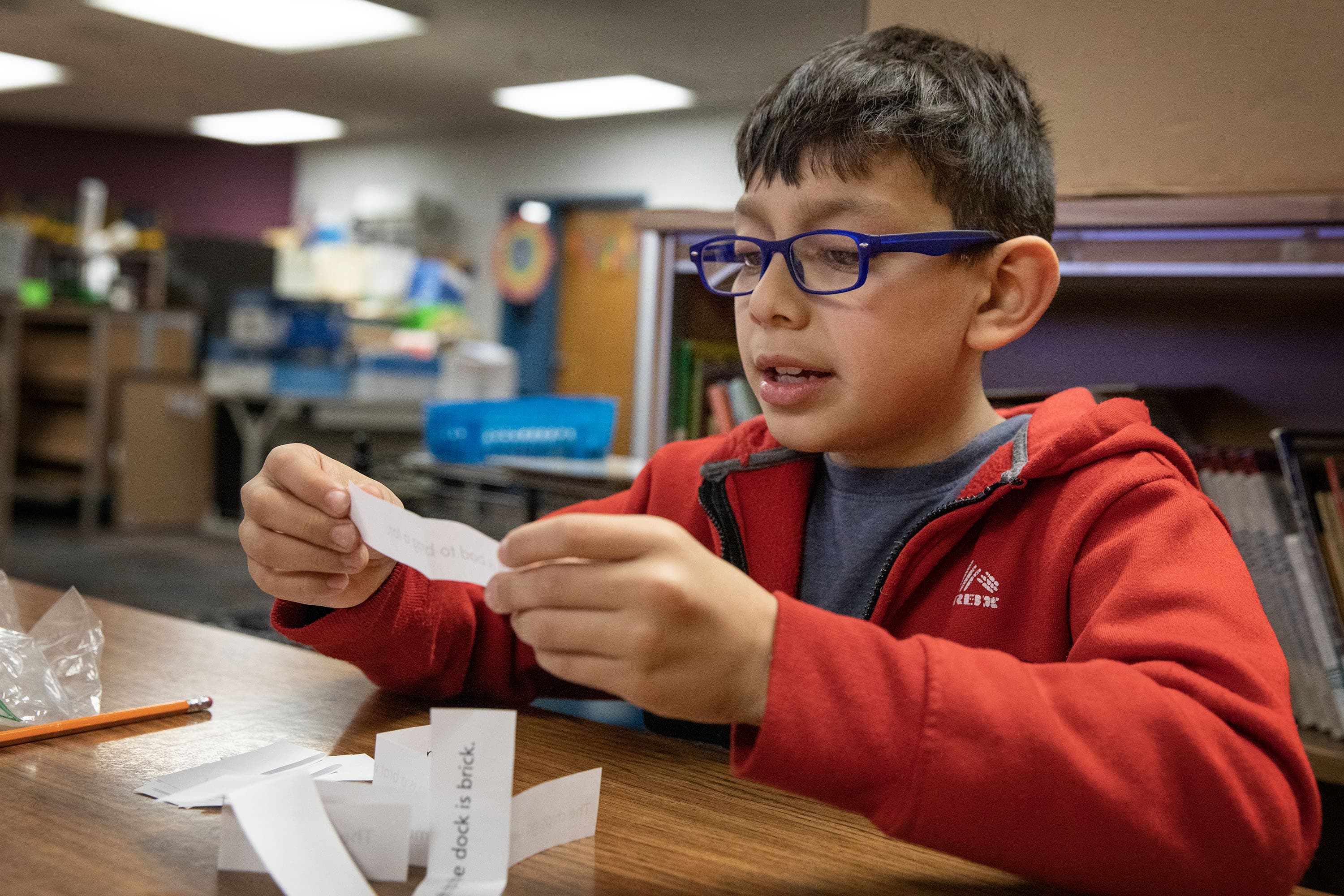

Third graders at Sumner G. Whittier School, in Everett, sound out words — syllable by syllable — on a recent morning. Teacher Audra Lessard asks each of the five students to carefully read a word aloud from a worksheet.

“Br - i - m … brim!” says Matthew.

“Cr - a - b … crab,” another boy, Kaua, says.

When another student, Arthur, hurries through the word, “branch,” Lessard nudges him to separate out each syllable.

The ability to pronounce written words this way is what literacy specialists call letter-sound knowledge — and it’s an important building block to reading proficiency. It’s also one of a handful of skills researchers say schools need to monitor in the early grades to identify students at risk of a learning disability, including dyslexia.

Whittier, a public K-8 school, identifies kids who need extra reading support through early literacy screening, a type of assessment that measures a suite of foundational skills, including how well a student can string together sounds or identify letters.

But such screening is uneven across Massachusetts. Some schools may use outdated tools or not screen kids at all. This has contributed to a patchwork landscape in which students from wealthier school districts are more likely to be screened for reading disabilities — and thus receive necessary intervention faster — than their disadvantaged peers, according to researchers.

To address that imbalance, the Massachusetts Board of Secondary and Elementary Education passed a new regulation in September requiring all school districts to screen students in kindergarten up to third grade twice a year from a list of pre-approved screeners. The new rule takes effect in July.

“You really have to screen all the kids, not just to identify potential dyslexia, but to identify where they're at, so that you can deliver the right service at the right time and try to catch kids before they fall behind,” said board member Michael Moriarty.

The change stems from 2018 legislation in Massachusetts requiring DESE to craft new guidelines to develop new screening protocols for students exhibiting early signs of dyslexia.

The new mandate promises to yield a lot more data about Massachusetts’ youngest learners that can help districts pinpoint what additional reading support they can offer to students.

That’s potentially powerful information, but the challenge for school leaders is how to convert that information into actionable next steps. The process involves time, money and patience, though the state is extending grant funding for such efforts.

Importance of high quality literacy screeners

A major concern among education advocates is that Massachusetts is not identifying students at risk of dyslexia early enough to offer interventions. State standardized test scores and National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) results also show that Black and Latino students, English learners and low-income students have inconsistent access to foundational literacy instruction.

Based on the 2022 NAEP results, the equity advocacy group Education Trust found Massachusetts to be one of the top five states with the largest disparities between kids from low-income and high-income backgrounds in 4th grade reading scores.

What's more, the number of students identified as having a specific learning disability, including dyslexia, nearly triples between the second and third grades, according to the 2020 Massachusetts Dyslexia Guidelines.

Nancy Duggan, executive director of Decoding Dyslexia Massachusetts, supports the new screening mandate since it leads to earlier awareness of literacy challenges. "Screening will give you sort of a red flag — hey, there's some risk here because there would be lots of reasons why kindergartners can't do the things that are in the screener," she said.

For decades, what screening tools to use and how often to use them were left up to districts. While the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education estimates that up to 300 of the state’s 400 public school districts are using a DESE-approved screener, there is no information on whether use of the screeners is uniform across all schools or how often they’re used.

Moriarty, the BESE member, said while many screeners exist, they differ widely in quality and purpose. And this had been a hurdle for districts. The state's role was to review and approve a list of quality screeners.

"We have people very carefully vetting what assessments are effective, and districts shouldn't have to just go out and figure that out for themselves," Moriarty said.

Under the new literacy mandate, schools must notify parents at least 30 days from the time of screening if results show a kid is reading significantly below grade level.

Investment in teacher training

But screening alone is not enough. One of the future challenges school districts face is how best to interpret data coming out of the screeners. Experts agree districts need to be able to read the results and determine what reading program best targets a student’s problem area.

When Lindsay Pouliot’s oldest daughter was in kindergarten in the Amesbury Public Schools in 2017, she scored low in a category called “rapid automatic naming” -- which measures how quickly a student can name letters.

But following the screening, there was no immediate follow-up assistance from the school such as remediation.

“That's too much time lost,” Pouliot said.

The Amesbury school district has since invested in more professional development for teachers. Using federal pandemic funds in part, the district in 2021 hired a dyslexia specialist, Holly Cole, whose job is to review data from the screening results, determine best reading programs and train teachers on those programs.

Cole says she may visit a school twice a day, sometimes to walk a teacher through how to administer a screener or how to teach a specific reading lesson.

Due in large part to the pandemic, close to half of first graders across the district were not reading on grade level at the start of the school year, Cole says. The goal is to have at least 85% reading at grade level by the end of the year.

"It's not enough just to do extra reading with the kid, I need to know [...] where are their areas of deficits," she said. "And if I look at their areas of deficits, can I hone in on the specific skills that they need in order to be able to do the next step? That's what intervention has to look like."

In the Everett Public School District, data from literacy screeners showed just how many students were reading two or more grade levels behind. It's a big reason why the district instituted reforms to its literacy program in the last two years, says Genevieve McDonough, K-8 English Language Arts and literacy director.

A team of teachers and specialists in the district grouped students together based on how well they scored on a subset of skills tested. Some were put in a group dedicated to growing vocabulary. And others, like the five third-graders working in Lessard's classroom at Whittier, were grouped together to work on letter-sound knowledge.

"We knew we had to do something to support students," McDonough said.

At Whittier, deciding what lesson each pod of students needs is the result of hours of discussion among teachers, administrators and specialists who study results from a screener called DIBELS.

Lessard was also trained on a whole new reading curriculum, which she said has given her strategies that she now uses to help her students with certain skills.

“What I didn't realize is that in order for the students to be able to orally read, they have to be able to decode the words, they have to be able to break down the words and understand, why that word says ‘cat,’” she said. “And I didn't understand all those phonics rules, so I wasn't good at teaching it.”

Lessard is seeing improvement in her students’ ability to read. In mid-December, the school administered another literacy assessment to check on students’ progress: her small pod of kids is reading words per minute at a faster pace in just seven weeks.

She’s also noticed improved confidence among her students.

"During the halfway mark I asked them all to close their eyes and said, 'OK, guys. Thumbs up, thumbs in the middle, thumbs down: Do you feel like you're a better reader?' "

And everyone put their thumbs up.

This segment aired on December 20, 2022.