Advertisement

Harvard Film Archive celebrates filmmaker Joyce Chopra with mini-retrospective

Filmmaker Joyce Chopra is no stranger to Harvard Square. In 1958, fresh from graduating Brandeis University, she and pal Paula Kelly opened Club 47 on Mt. Auburn Street, modeling it after the Parisian cafés they’d frequented during semesters spent studying abroad. They hired a Boston University freshman named Joan Baez to perform on Wednesday nights, and the club quickly became a mecca for the folk music revival, with these two 22-year-olds providing early gigs for Tom Rush, Judy Collins and Joni Mitchell. (According to legend, a young Bob Dylan once sang songs between sets for free, just so he could say that he’d played Club 47.) The place is still packing them in today, relocated a few blocks over on Palmer Street and rechristened Club Passim. But Chopra sold her stake in the café barely a year after it opened, headed home to New York City with dreams of making movies.

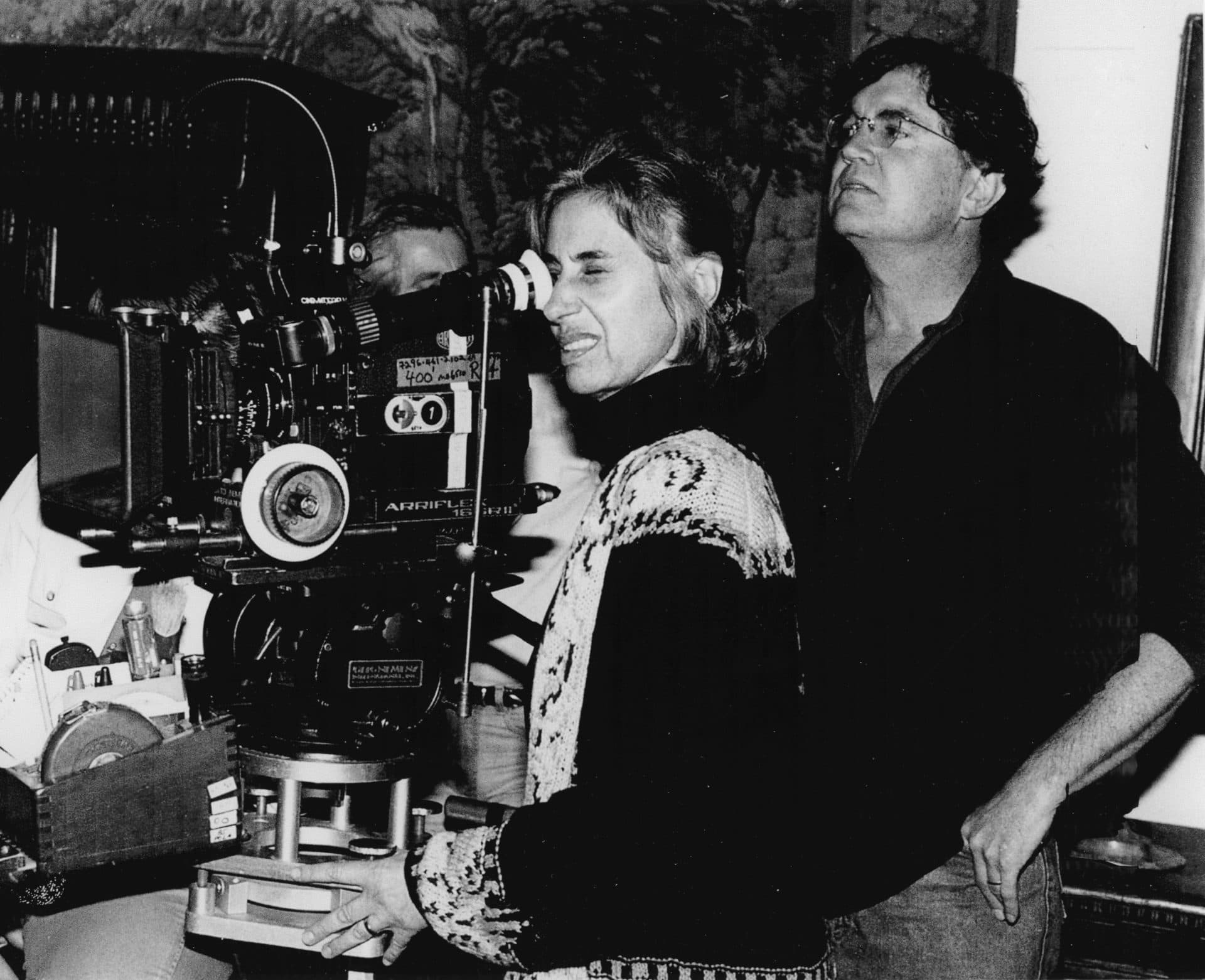

She’ll be back in the neighborhood this Friday night for the Harvard Film Archive’s “Joyce Chopra, Lady Director,” a mini-retrospective showcasing her seminal 1972 documentary short “Joyce at 34,” followed by a new 4K restoration of the filmmaker’s still-astonishing 1985 feature debut, “Smooth Talk.” The event is being held in celebration of Chopra’s recently released memoir “Lady Director,” a blisteringly candid and compulsively readable tell-all from a trailblazer who isn’t afraid to name names. The book arrives during an overdue reconsideration of a career stifled by chauvinism and Hollywood politics, with Chopra’s groundbreaking early documentaries now being showcased on the Criterion Channel and the long out-of-circulation “Smooth Talk” at last available to a younger generation of movie lovers who grew up in rightful reverence of its star, Laura Dern.

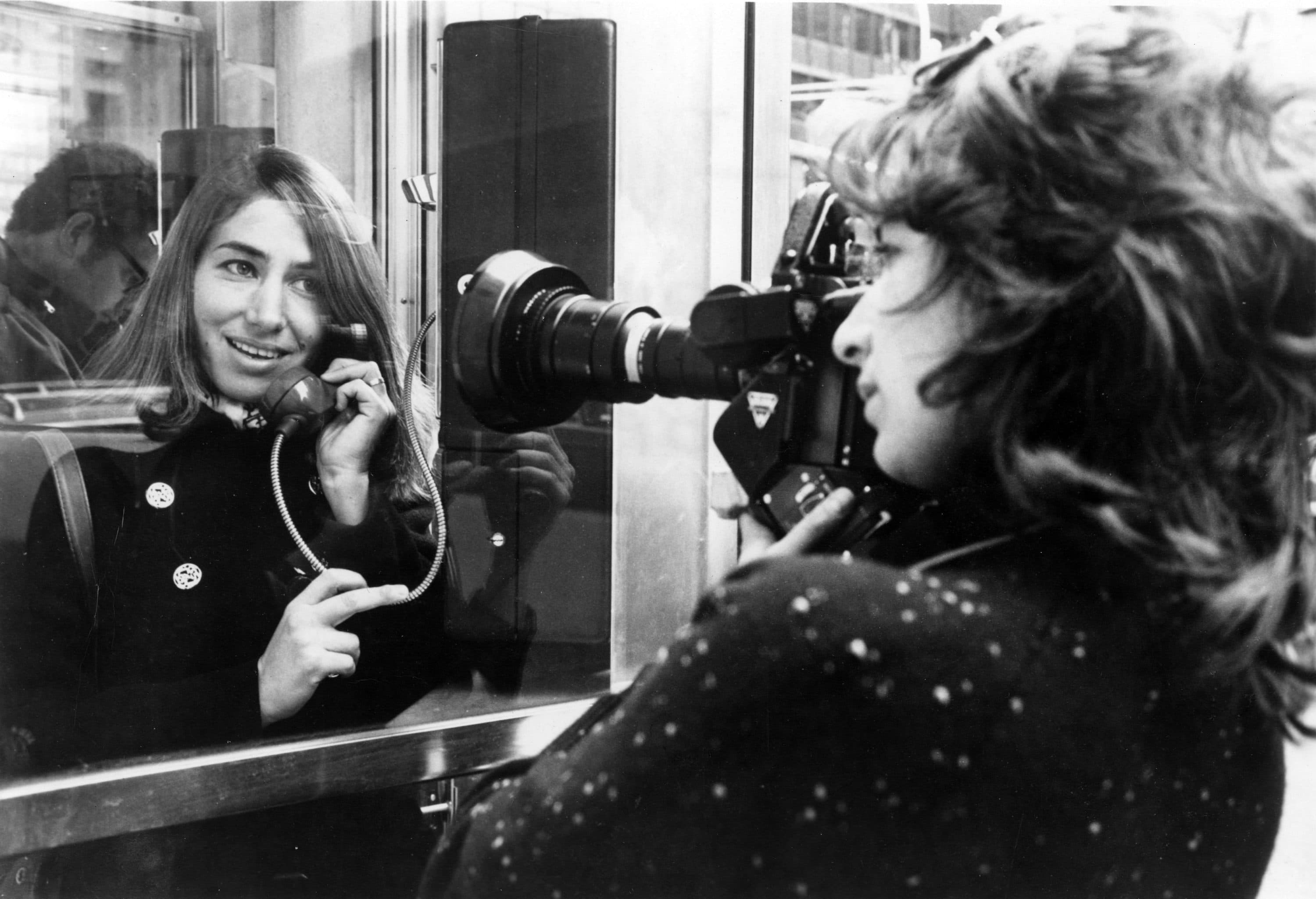

Chopra apprenticed under Richard Leacock and D.A. Pennebaker at the start of the cinema verité movement, before striking out on her own with vivid female portraiture shorts for public television. The aforementioned, autobiographical “Joyce at 34” begins with the live birth of her daughter Sarah (scandalously, the first time such a thing had ever been seen on TV) and chronicles the filmmaker’s attempts to juggle motherhood and her career, most tellingly via the sight of Chopra attempting to cut the film we’re watching on a flatbed Steenbeck editing machine with a toddler on her lap. It doesn’t go well.

The skeleton key to this filmmaker’s entire oeuvre might be 1975’s “Girls at 12,” during which Chopra follows a handful of boy-crazy Waltham tweens several decades before such a term was even invented, allowing us entry to a secret girls’ world of crushes, heartache and the anxieties of adolescence. So many stray moments and details from “Girls at 12” ended up dramatized 10 years later in “Smooth Talk,” which Chopra and her husband, esteemed playwright and author Tom Cole, freely adapted from Joyce Carol Oates’ harrowing 1966 short story, “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?”

Dern stars as Connie, a rebellious smalltown girl on the cusp of womanhood. She’s constantly fighting with her mother (Mary Kay Place) and sneaking off with her friends, slathering on makeup and changing into skimpy clothes before they all go flirt with older boys at the mall. It’s an eerie, unsettling film in which female sexuality feels like an awesome, destabilizing superpower that our heroines haven’t quite figured out how to handle just yet. Things get especially discomfiting once Connie catches the eye of Arnold Friend (Treat Williams), an aging hunk in a gold convertible and aviator shades who has a way with words and an eye for underage gals. He also might be a serial killer, or at least he was in Oates’ story.

Chopra’s film is somehow even more ambiguous than the original author’s sparse prose, building to an almost mythical, 25-minute pas de deux during which Arnold tries to coax Connie off her front porch and into his backseat. That rickety screen door at her family farmhouse becomes a Rubicon between childhood dreams and the alluring, untold dangers of the adult world. With all due credit to Williams’ disarmingly cheesy menace (a teenage girl’s “trashy daydream” of a man, according to the movie), there’s simply no way to overstate the skill of Dern’s performance here.

Just 18 at the time of shooting and in her first leading role, Laura Dern has a way of looking 11 years old in one shot and 25 in the next, her languorously long limbs split-second shuttling between Connie’s coltish confidence and childlike trepidation to such uncanny, evocative extent that Oates later wrote: “Dern is so right as ‘my’ Connie that I may come to think I modeled the fictitious girl on her, in the way that writers frequently delude themselves about notions of causality.” Chopra says in her book that Dern’s audition gave her the same feeling she got the first time she heard Joan Baez singing at Club 47. A star is born.

Advertisement

“Smooth Talk” was co-produced by PBS’ “American Playhouse,” and like a lot of independent movies from the 1980s, suffered from a tangle of rights issues that made it difficult to find on home video for decades. Thanks to the tireless championing of the film by Siskel and Ebert, I tuned in during what must have been one of those early “American Playhouse” airings back in 1987, when I was way too young to be watching it. The movie burrowed into my brain like a tick, and during the premiere of this new restoration at 2020’s virtual New York Film Festival I was astounded by how vividly I’d remembered so much of what I’d seen so long ago. There’s a moment near the very end that I’ve never been able to shake, when Dern alters her eyes and posture ever so slightly while walking toward the camera, and it feels like you’ve just witnessed in real time the passage between innocence and experience.

Despite rumors that festival founder Robert Redford deeply disliked the film, “Smooth Talk” won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance that year and found an ardent fan in director Brian De Palma, who sought out Chopra after a Toronto International Film Festival screening and immediately introduced her to his agent. Hollywood beckoned, but it was a relationship that was not meant to be. The “Smooth Talk” trio of Chopra, screenwriter Tom Cole and cinematographer James Glennon were hired by producer Sydney Pollack to adapt Jay McInerney’s white-hot bestseller “Bright Lights, Big City” for superstar Michael J. Fox. Four weeks into filming, Pollack fired all three of them, causing the kind of publicity nightmare and catty, trade paper hit-pieces that end careers.

In retrospect, an old Hollywood warhorse like Pollack who helmed Redford projects like “The Way We Were” and “The Electric Horseman” couldn’t possibly be a worse steward for New Yorker McInerney’s cocaine-frenzied discotheques and hip, second-person prose tricks. The “Bright Lights” he eventually shepherded to the screen – directed by James Bridges of “The China Syndrome” and shot by “The Godfather” cinematographer Gordon Willis in 50 shades of beige – is as stodgy as any mid-century, prestige literary adaptation, desperately out of touch with the times.

Things went from bad to worse when Diane Keaton hired the long-suffering Chopra to helm her long-percolating dream project, “The Lemon Sisters,” about three female doo-wop singers growing up together amid the changing fates of the Atlantic City boardwalk. The star had originally intended to direct it herself, and really probably should have, as all the odd motivations for one of the strangest performances of Keaton’s career remain locked entirely inside the actress’ own head. She’s inscrutable, and abominable in this one.

After a disastrous shoot, Chopra found herself shut out of the editing room at her star’s request before eventually being welcomed back with open, unfriendly arms by producer Harvey Weinstein – the both of them spending an ugly, sweaty summer trying to cut around Keaton’s bizarre, intensely unpleasant turn by banishing her to wide shots and background actions. Eventually, even a monster like Harvey agreed the only way to get the film back up to feature length was Chopra re-shooting extensive black-and-white flashbacks to the main characters’ childhoods: “Girls at 12” all over again. (These scenes are the only good ones in the movie.)

Chopra’s career was salvaged by a lark. “Murder In New Hampshire: The Pamela Wojas Smart Story” was a trashy 1991 TV movie with a sassy kick and blockbuster ratings. Chopra coaxed an extremely funny, very knowing performance out of rising star Helen Hunt and afterward settled into directing a decade or two of not-bad, melodramatic crime drama cheapies ripped from the headlines. The Chopra movies from this era that I’ve seen are often extremely watchable without being particularly good, and if anyone has a line on her “L.A. Johns,” in which Blondie’s Debbie Harry plays a Hollywood madam, my emails are open. In 2001 she also helmed a two-night CBS TV miniseries based on Joyce Carol Oates' then-recent novel "Blonde," a project that somehow escaped all the hysterical hand-wringing that surrounded Andrew Dominik's 2022 adaptation. (But then again, so did Joyce Carol Oates. Curious how few of these rage-case film critics actually read books.)

The last, and maybe best film of Chopra’s late career television run is one of the most unexpected. A 2006 toy tie-in for the Disney Channel’s “American Girl” doll series, “Molly: An American Girl on the Home Front” is one of the filmmaker’s personal favorites and a shockingly effective melodrama. The kind of movie you’d only ever watch if you had a kid the right age or were perhaps writing an article on the filmmaker, it’s nonetheless a handsomely mounted, three-hanky weepie about a spoiled, 11-year-old brat growing up in middle America during WWII and discovering there’s a whole world happening out there beyond her petty concerns. The film boasts some really lovely work by Molly Ringwald as the protagonist’s mom, and the best scenes come back again to “Girls at 12,” combined with the filmmaker’s own childhood reveries of life during wartime. I can’t believe I cried at a movie based on the backstory of a plastic doll.

"Joyce Chopra, Lady Director" screens at the Harvard Film Archive on Friday, Feb. 3.