Advertisement

‘Keep the language in you’: Immigrant households in Boston seek to preserve native tongues

No matter how you say it, language is the key to keeping traditions and culture alive and vibrant in immigrant communities. That is particularly true for the three dominant immigrant groups in Dorchester and Mattapan who are working to keep their native languages alive among first-generation Americans.

The Vietnamese, centered in Fields Corner, Cape Verdeans in Uphams Corner and Bowdoin-Geneva, and Haitians throughout Mattapan and Dorchester are at a crossroads in their immigration stories with each group mounting renewed efforts to teach kids to speak the languages of their parents and grandparents. Whether it’s through a church program, a specialized school or even with a children’s storybook, each has found ways to keep the language relevant.

“In terms of losing the language, maybe it takes another 40 years instead of another 20 years like happened for the Italians and Germans,” said Hiep Chu, who runs a religious education program at St. Ambrose Church in Fields Corner that doubles as a Vietnamese language class. “They didn’t have the efforts we have. They just told everyone to integrate and speak English and go to school. We integrate too, but we don’t forget who we are.”

In Mattapan’s Mattahunt School, a similar battle is being fought to preserve and encourage the Haitian Kreyol language through the Toussaint L’Ouverture Academy – the first dual language Haitian Kreyol-English school in the country.

Said Judith Mathieu, a teacher: “I honestly think when a language dies, it means part of you is gone. Part of your identity is in the language and without that language you’re losing part of your culture. That is very sad. One way we can make sure it keeps going is having a program like this at school with teachers that speak the language that are Haitian.”

The latest demographic information released by the Boston Planning and Development Agency (BPDA) speaks to the mounting existential challenges facing all three ethnic groups. While each saw population growth in Boston, those speaking the native languages in Dorchester had declined from previous years.

In 2023, Dorchester had an official population of 124,865 residents and Mattapan had 26,938 residents, an increase from 2016. Those speaking Haitian Kreyol in Dorchester were 9,364 (7.9%), and in Mattapan 4,116 (16.4%). That was a decline from 2016 when there were 10,941 speakers in Dorchester (9.5%) and 4,389 speakers in Mattapan (19.1%). For the Vietnamese in Dorchester, in 2023 there were 7,095 speakers (6%) as compared to 9,280 speakers (8.1%) in 2016.

The city stopped keeping track of the Cape Verdean Criolo language in 2017. However, in 2016 there were 4,351 speakers (3.8%) in Dorchester, and a year later there were 4,045 (3.5%). The city reported no numbers after that.

The First Book: ‘Tiagu Y Vovo’

Dorchester’s Djofa Tavares grew up in a tight-knit Cape Verdean family where everyone on her street was Cape Verdean and the adults did their best to speak Criolo.

“For me the language was just a thing I did,” she said. “As I got older and had children, I wanted them to understand and speak Criolo. I had left, but we went back to the same neighborhood because I wanted my kids to have the upbringing with the Criolo language. They all speak it now.”

But that it isn’t the case for many from the island, where two groups immigrated to the Boston area in distinct waves. Those who arrived before 1975 carried a Portuguese passport. After Cape Verde won its independence in 1975, emigrants carried a Cape Verdean passport along with a certain pride.

A teacher at the Russell School in Dorchester, Tavares said she started to see the language slip in both groups. Many adults that grew up speaking Criolo had begun to lose it.

“As we talk about the future – the children – it’s going to be more difficult,” she said. “As a teacher in this neighborhood, I see a lot of my students that can’t speak to their grandparents. That’s sad. Right now, there’s a movement to keep the language alive…There are folks that have been here four generations and are now realizing the mistake of not keeping the language.”

Tavares collaborated with relatives to create what is believed to be the first children’s book in Criolo and English, called “Tiagu Y Vovo.” The book is all about a boy from Cape Verde who comes to live with his grandfather in the United States. In preparation for school, his grandfather teaches him English, but also instills in him the importance of not forgetting Criolo.

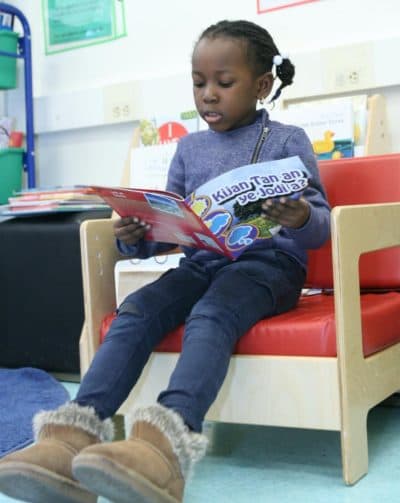

Tavares and State Rep. Chris Worrell have been on an informal tour around Dorchester and Roxbury in recent weeks to give the book to students. At the Conservatory Lab Charter School on Columbia Road on Feb. 2, their appearance was a hit with Criolo and non-Criolo speakers.

"I honestly think when a language dies, it means part of you is gone. Part of your identity is in the language and without that language you’re losing part of your culture."

Teacher Judith Mathieu

Worrell said he felt it was important to highlight someone in his district trying to preserve a vibrant neighborhood culture. “Being from an immigrant family, I know what it’s like growing up in a household with multiple dialects,” he said. “Your language ties you to your culture and your culture is something to cherish…That’s why spreading this book to our Black and Brown youth is so important so that our young people know and appreciate their roots.”

In her spare time, Tavares also teaches Criolo classes to adults who never got the chance to learn the language – a sensitive topic in the community; in some cases non-speakers can be ostracized by those who speak Criolo.

“I had one lady in her mid-70s that learned from me and said it was the first time in her life she felt like a real Cape Verdean,” said Tavares.

‘I don’t want to be whitewashed; I want to be Asian’

Every Sunday afternoon, nearly 300 Vietnamese youth gather in the basement of St. Ambrose Church for religious education classes. At the same time, adults use the opportunity to fold in Vietnamese language instruction.

Hiep Chu and his wife, Nhung Nguyen, run the program with about 34 other volunteers, all bilingual speakers of both Vietnamese and English, known as the “bridge generation.”

Said Nguyen: “It is very difficult to teach the language in a family. For the first kids, it’s easy. The parents speak it to them, and they speak to the parents while learning English in school. The second child is much different because they have another person in the home to speak English to. In the beginning, we might force it a little to help things along. Language is a part of the culture. If we can show them it’s important, that helps. Kids are curious and want to know what the adults are saying in Vietnamese.”

While there are other language classes available in the Vietnamese community, St. Ambrose holds a special corner of the market as it is the largest Vietnamese church in the Boston area – with about 2,000 members and packed Masses in Vietnamese and English every week.

“For us teaching you, the object isn’t to make you speak perfectly, but to keep the language in you,” Chu told a class of 8th graders during a recent Sunday class. “We know it’s a losing battle, but we want to prolong the language as long as we can.”

The mood among students in the class runs from ambivalent to enthusiastic. Most say they want to be able to communicate with their parents or their grandparents, who in many cases live in the same multi-generational home with them.

Vincent Nguyen said he wants to learn the language because he doesn’t want to lose his identity. “I just don’t want to be whitewashed,” he said. “I want to be Asian. People ask me if I’m Vietnamese and then they ask me if I can speak it. I don’t want to look dumb. I really want to learn my culture and not just be part of someone else’s culture, not knowing my own.”

Added Averlyn Truong, who wants to speak Vietnamese fluently: “There’s a lot of pressure on kids who don’t speak Vietnamese. It can be frustrating that I don’t know my own language. It can make you feel like you don’t care about the Vietnamese people and only care about America. A lot of the older generation is sad and disappointed by this. They’re hoping that our generation will speak more Vietnamese and not less.”

It’s OK to speak Kreyol

In the middle of a thick wooded area in Mattapan, the sounds of Haitian Kreyol can be heard echoing out the windows of the of the Toussaint L’Ouverture Academy at the Mattahunt School, the first Kreyol-English school in America, where about 70 students in grades K1-4 are part of the academy’s program.

It is a critical point on the map in Boston for retaining the Kreyol language, says Priscilla Joseph, a K-2 teacher and founding member of the school. “In my household growing up in Boston I was that kid in the beginning that was like, ‘I don’t do the Kreyol thing.' Back in the day a lot of kids were like that. My mom was told to only speak English with us.”

“I think the language is very important. We can’t just speak only English. We’re our own country. We are not just American.”

Student Averlyn Truong

She said it wasn’t “cool” to be Haitian at the time, but as she got older, things changed in how people viewed Haitian culture – and she found that others like her now wanted to speak Kreyol. That’s when the revival happened for them.

K-1 teacher Rose Bourdeau said new arrivals from Haiti in the 1980s downplayed their Haitian identity, in some cases because of the erroneous stigma attached to Haiti in the early years of the AIDS epidemic.

“Everyone wanted to speak English to blend in as an African American and not be identified as Haitian by the Kreyol,” she said.

Although it is universally spoken in Haiti, elites who control the country’s affairs have often cast Kreyol as inferior to French, Haiti’s colonial language. Part of the mission of the school is to convince parents that Kreyol is okay, and even an advantage in the United States.

Joelle Gamere, assistant principal for the Academy, said she grew up learning the language, but wasn’t going around waving the Haitian flag.

“Haitian Kreyol was an opportunity for me to work for BPS,” she said. “It’s only because I spoke Haitian Kreyol that got me this job. The language opened many doors for me…It’s a mindset for folks when they come here, they think they have to assimilate and do everything like in the U.S. and in English…But leaving their language behind could cause them to miss opportunities like I had.”

For her part, Priscilla Joseph, who is 38, said her generation missed out on learning their language, but they are using the Academy to right that wrong. “A lot of friends my age don’t know Kreyol, but they want their children to learn it and they end up learning it together,” she said.

Back in the basement of St. Ambrose Church, it’s an eighth grader’s understanding that sums it up for all three languages and all three efforts.

“I think the language is very important,” said Averlyn Truong. “We can’t just speak only English. We’re our own country. We are not just American.”