Advertisement

Review

Emily Brontë biopic takes many thrillingly salacious liberties

“How did you write ‘Wuthering Heights?’” pinch-faced buzzkill Charlotte Brontë asks her dying sister during the opening moments of “Emily,” actress Frances O’Connor’s atmospheric and welcomely irreverent directorial debut. All artist biopics are to some extent or another attempts to “solve” their subjects, and the mysteries of how an informally educated and unworldly homebody like Emily Brontë came to write such a singularly radical Gothic romance have been swirling around ever since Charlotte outed author Ellis Bell as her recently deceased sibling way back in 1850. Beyond being an index of backhanded compliments, the surviving Brontë sister’s words kicked off a legacy of wild speculations and dopey literary conspiracy theories fueled by chauvinism, intellectual snobbery and our culture’s unfortunate disinclination to believe that sometimes people are just really good at making stuff up.

O’Connor’s film — for which she also wrote the screenplay — is likewise mostly made-up stuff. So little is known about Emily’s actual life and times that the picture is free to indulge in thrillingly salacious speculations and semi-informed attempts to explore the roiling passions and mercurial contradictions that might have inspired our socially awkward wallflower to put pen to paper. It’s a very modern movie about the idea of being Emily Brontë, misfit of the moors. She’s played by Emma Mackey (from the Netflix series “Sex Education,” which I apparently need to watch) with deep-set eyes in a faraway gaze often interrupted by reckless, impulsive gestures. A head taller than her sisters and a good deal darker in both hair color and disposition, Emily’s a proto-Goth girl sitting off by herself in these Victorian church pews, bored to catatonia by the sermons of hunky new curate Mr. Weightman (Oliver Jackson-Cohen).

Emily is treated like an alien by sisters Charlotte (Alexandra Dowling) and Anne (Amelia Gething) but has a kindred spirit in her dissolute brother Branwell, played with a touching guilelessness by Fionn Whitehead. An aspiring transcendentalist bellowing the magnificently corny motto “freedom in thought!” he brings his kid sister along for wild afternoon adventures on those windy Yorkshire cliffs, introducing her to liquor and opium, as well as a hobby of peeping through the windows of their dull, hoity-toity neighbors that readers might recognize from “Wuthering Heights.” (It’s the one sequence in which the movie strays a little too close to becoming a “Shakespeare in Love”-style Easter egg hunt.) Branwell has all the swagger, braggadocio and insufferable pretensions of an author for the ages. Everything except the talent.

I recently started reading “Wuthering Heights” myself (better late than never, I guess) and what’s immediately striking to anyone who feels like they’ve already absorbed the story through cultural osmosis is how forbidding and strange it feels. It’s a novel of not just illicit passions but of poisonous resentments and their grotesque, distorting effects. There’s an almost feral quality to the prose that’s a million miles removed from Laurence Olivier’s dashing, tortured stableboy in William Wyler’s beloved 1939 adaptation, famously shot on the moors of Ventura, California. (Amid the dozens of screen versions, I’ll put in a good word for “Fish Tank” director Andrea Arnold’s bracingly nasty 2011 take, somehow the first to cast a Black actor as Heathcliff.)

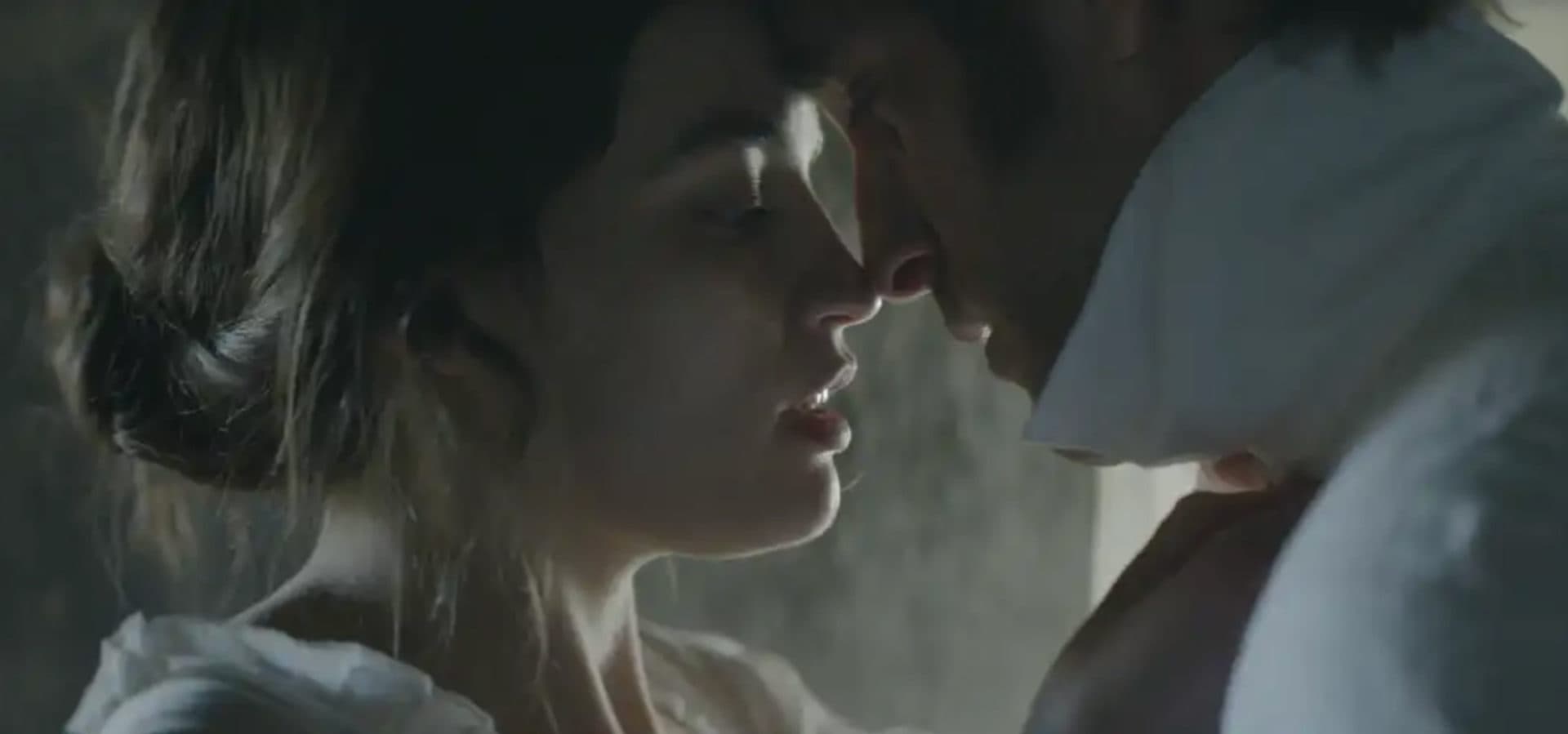

Similarly, there’s a throbbing vitality to the filmmaking here that’s a far cry from your classical corseted dramas. Having played Emma Bovary for the BBC and starred in “Mansfield Park” during the late-‘90s Jane Austen gold rush, this is a genre with which O’Connor is intimately familiar, but her “Emily” has a thrillingly reckless visual sensibility. The camera hurtles through these rough-hewn landscapes with jump-cuts punching us through the story in leaps and bounds. Emily’s casual blasphemy earns her the ire and rapt fascination of our handsome, cowardly curate, who is initially assigned with teaching her French until the lessons inevitably become extracurricular.

The real-life Weightman was actually linked with sister Anne, but why deny Emily — or us — the pleasures of a good, old-fashioned bodice-ripper? (I seriously wasn’t expecting the sexiest movie in theaters right now to be the one about Emily Brontë.) O’Connor gins up a randy melodrama of missed connections, undelivered letters and deathbed confessions. None of “Emily” has anything to do with the historical record, but it’s a fine tribute very much in keeping with the doomy, romantic sensibility of its subject, as well as the unfortunately unpopular idea that sometimes the most enduring stories are the ones somebody just made up.