Advertisement

At 92, a Maine woman has been adding to the climate record for more than half her life

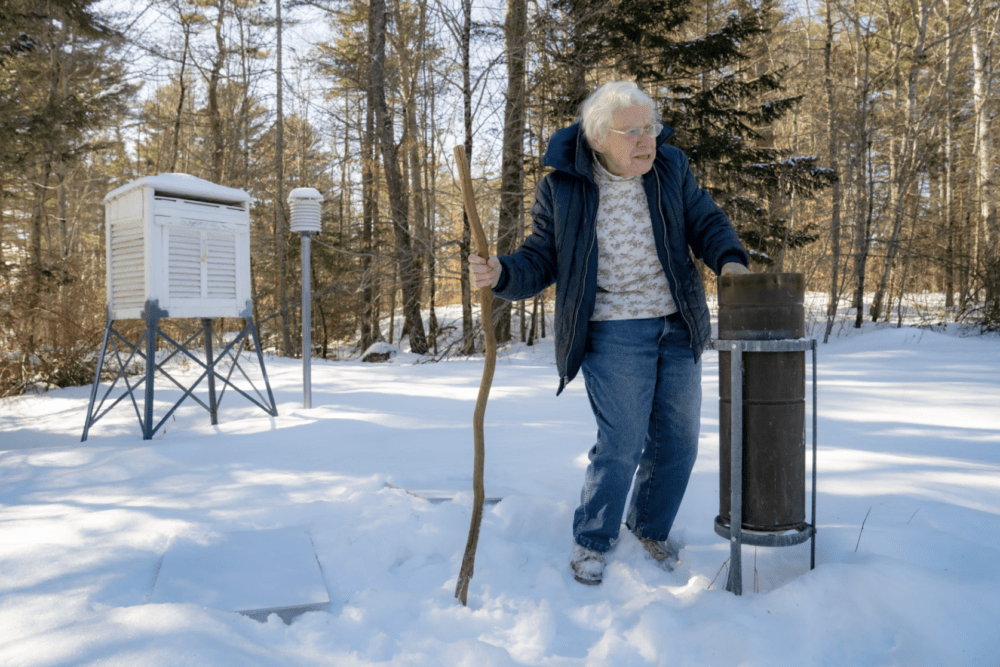

Any time of day if you're wondering what the current low or high is in Newcastle, there's a good chance 92-year old Arlene Cole knows.

"So far today, and you will note that's in pencil," says Cole, on a frigid morning in early February. "...so far, it was three for a low and 12 for a high."

Cole likes to check the weather throughout the day, but she won't take an official reading until 5:00, just as she has every day for more than half a century. She's part of a nationwide network of volunteers who record the daily weather for the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration.

"I have 57 years of records," she says. "I give my records into NOAA every month."

She pulls out a sheet of paper with her data for the month of January. It includes the daily highs and lows, 24-hour totals for rain and snow, and the accumulation on the ground. On this day, there's about eight inches of snow outside. But a couple weeks ago, the weather was dramatically different.

"January 13," she reads. "The high was 52. The low was 34. We had 1.75 inches of rain. We did not have any snow. There was no snow on the ground."

Cole can tell you the weather for each day as far back as 1957. That's when she started a personal diary with her observations. She says she's always been interested in the weather. She grew up on a farm not far away in Jefferson, where her father's daily decisions about chores were dictated by the weather.

"Weather was important," Cole says. "Every morning — our kitchen door faced north, but then you went around to the shed door, which faced east — and he would kind of pause there and look at the weather."

She became an official observer for NOAA in 1965, taking over the role for a friend who passed away. She's never missed a day, even as she raised a family, worked as a ballot clerk, and helped launch a local historical society. The few times she's been out of town, neighbors and family have filled in. Over the years, Cole has contributed more than 20,000 readings to NOAA's database.

"It's part of daily living. I don't really think anything about it," she says. "It's just one more thing, like I set the table for supper, I go out and read the temperatures."

For Cole, it's routine. But for scientists at NOAA, her readings are essential for understanding weather and climate change.

"Their observations are the backbone of our nation's climate network," says Nikki Becker, the Observing Program leader at the National Weather Service forecast office in Gray, Maine. NOAA's observer program officially started in 1890, but Becker says records go as far back as colonial times.

Advertisement

"A lot of these, the precursor of them, they weren't probably originally thinking climate," Becker says. "But as it evolved over time, these records were archived. And then you can use it for comparisons."

Becker says even with today's technological advances, hand measurements by volunteer observers are the most efficient, cost-effective way to collect data. NOAA provides each observer with the same standardized equipment, whether they're in the Aleutian Islands in Alaska or in Midcoast Maine.

Just a few steps outside Cole's front door in Newcastle, she walks past a 60-inch stake that measures snow depth towards a rain gauge. It's a metal cylinder about half as tall as she is that collects rain and snow, which Cole brings in every night to measure.

Temperature readings are easier: she takes those from a digital reader on her kitchen counter that's hooked up to a thermometer outside. Cole has been recognized with multiple awards for her years of service as an observer, but, at 92, she admits she's slowing down.

"And little by little I give things up," she says." There is no question. I am not the gay blade I used to be. But I don't see why I can't go out and do the weather."

And so she says she'll keep compiling data as long as she's able, helping scientists along the way.

As the former director of the National Weather Service once put it: "Forecasts are for today, but observations are forever."

This story is a production of the New England News Collaborative. It was originally published by Maine Public.