Advertisement

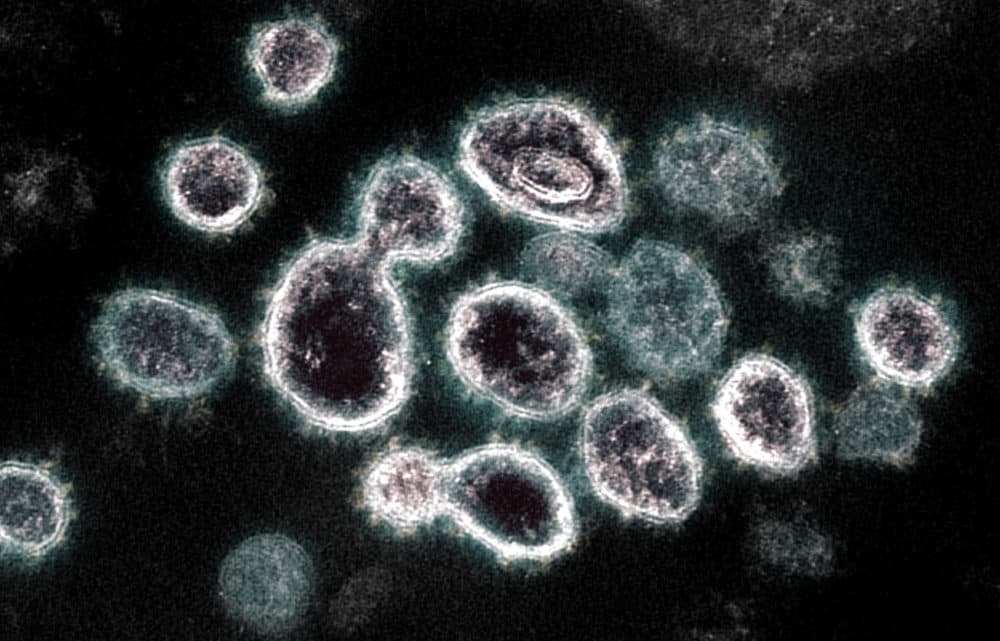

Watching the wastewater: Mass. COVID at lowest level in a year

There is good news on the COVID front. Levels of the coronavirus found in Boston-area wastewater have dipped to the lowest level in a year.

“It is worth celebrating,” said Shira Doron, an epidemiologist and chief infection control officer for the Tufts Medicine health system.

“It's very heartening,” added Larry Madoff, medical director of the Bureau of Infectious Disease and Laboratory Sciences at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. “We're really at the lowest point they've been in over a year.”

At the same time, a new study, published this week in the journal JAMA Network Open, suggests COVID has become less dangerous in Massachusetts.

The researchers looked at patient records from the Mass General Brigham hospital system and found that — after controlling for differences including demographics, vaccination status and prior infection — coronavirus infections appeared less likely to cause death or hospitalization.

“The virus is truly — or intrinsically — less severe at the moment,” said lead author Hossein Estiri, a professor at Harvard Medical School.

Low wastewater numbers

Measuring the amount of coronavirus virus in sewage samples has become a useful tool for public health officials to estimate how widely the virus is circulating. This metric has become particularly valuable as COVID testing rates have dropped, and free testing sites have closed.

Last April, COVD was ebbing as Massachusetts emerged from the omicron wave, an enormous surge in infections at the end of 2021 and the beginning of 2022. This year, wastewater measurements of COVID again dropped through the late winter and early spring.

Bill Hanage, an epidemiologist at Harvard's T.H. Chan School of Public Health, said the primary driver behind these drops is likely the same: “A lot of immunity from the [recent] infections."

Scientists have learned that after a person comes down with COVID, there is often a window of time when the body is unlikely to get infected again — or spread the illness to other people.

Experts also believe warmer spring weather drives more people outdoors, where COVID is less likely to spread. Madoff pointed to high rates of vaccination in Massachusetts as another factor contributing to the population’s immunity.

“I think also there's some luck involved here,” he said. “We haven't had a new variant that's substantially different than the variants that we've seen before, and so there hasn't been a chance for something to escape that immunity.”

Madoff, Doron and Hanage all agree that future wastewater levels — and future COVID levels — are unknown. “Numbers will start to climb at some point,” said Harvard’s Hanage. “Exactly when remains to be seen.”

A less dangerous virus

Trying to predict the future of COVID has been a challenge even for experts, but a new study provides hope the coronavirus may be loosing some of its punch.

In the early days of the pandemic, many hospitals were overwhelmed and scrambled to find enough ventilators for all the gravely ill COVID patients coming through their doors. A lot has changed. With the development of COVID vaccines and medications that help treat COVID, many people have returned to their regular routines. Public health officials don't currently worry that COVID will overwhelm the health care system.

Harvard’s Estiri and his team wanted to know whether the drop in rates of death and hospitalization from COVID was the result of factors like vaccines and broader immunity, or whether COVID itself was becoming less severe.

By looking at patient records, his team concluded the coronavirus became markedly less severe between July 2021 and March of last year. “A huge drop in severity,” Estiri said.

After March 2022, the team found the severity of COVID plateaued and stayed at the same lower level through the end of that year.

Estiri theorizes the coronavirus's genome may be evolving in ways that make it less dangerous, but he cautioned it's hard to know what new mutations might bring. His team is currently working on an algorithm designed to predict the future severity of COVID.

In addition to changes in the virus, the researchers found that vaccination helped make COVID even less dangerous for patients.

“For an average person, the risk of hospitalization was 55% lower — and mortality was 68% lower — if they had been vaccinated compared to not being vaccinated,” said Alaleh Azhir, a coauthor of the study and a student at Harvard Medical School.

Doron, at Tufts Medical Center, said the researchers' findings match her clinical experience.

“When this all started, most of the patients were in the [Intensive Care Unit] and, I mean, they were really, really sick,” she said. “Now they're almost never in the ICU, even when they come into the hospital.”

She said the combination of lower severity and low wastewater numbers should prompt the state and country to reevaluate precautions. Massachusetts concludes its public health emergency in May, and the federal COVID emergency ended earlier this week. But Doron would like to see the five day isolation period after a positive COVID test removed, as well as the requirement that non-U.S. citizens to show proof of vaccination before entering the country.

“It’s a great time to reassess,” said Doron. “It is just as dangerous to breathe on somebody who's vulnerable when you have the flu or [Respiratory Syncytial Virus] or the common cold, as it is with COVID these days.”