Advertisement

Review

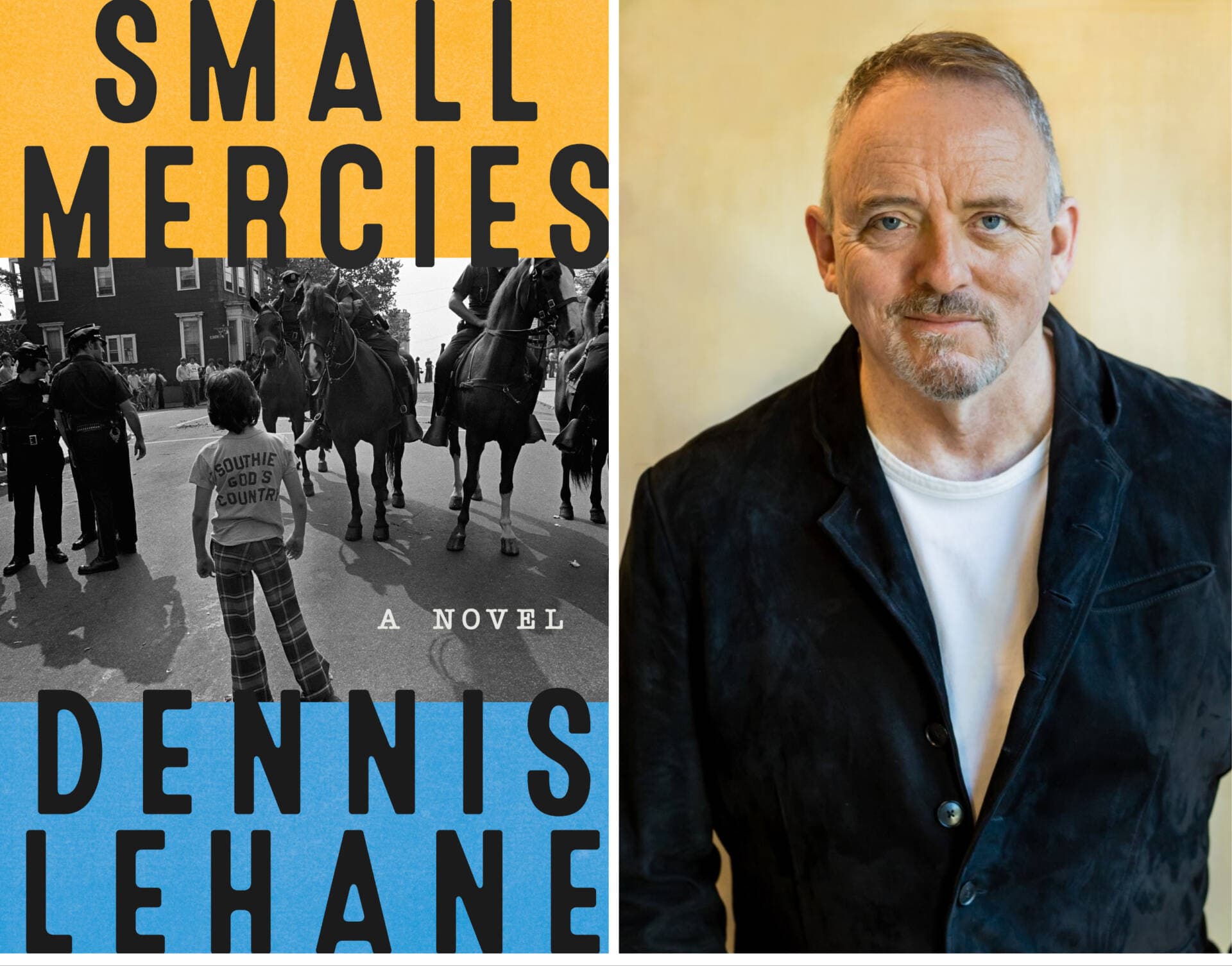

Novel 'Small Mercies' illuminates a turbulent period in Boston's history

As we’ve been reminded more than ever during the pandemic, you only get one set of high school years. As we’ve also been reminded by countless “Best of” lists ranking Massachusetts high schools, not all schools offer the same quality of education.

The state of American education has been in the news a lot recently, but we can look to history for a deeper understanding of the issues in modern schooling. Nearly 50 years ago, busing — a way to desegregate schools by transporting students between white-majority schools and Black-majority schools — threw school inequality into high relief in many Boston neighborhoods.

Dennis Lehane’s new novel “Small Mercies” explores the massive upheaval caused by Boston’s 1974 court-ordered busing. The novel is Lehane’s 14th work of fiction, the latest in a long and rich line of novels, historical novels and literary crime novels.

The court order impacted many Boston schools, but those in the largest white-majority and Black-majority neighborhoods were South Boston High School and Roxbury High School. “Small Mercies” is explored primarily through the lens of South Boston residents.

The busing order by U.S. District Court Judge W. Arthur Garrity, Jr. took effect in September 1974. “Small Mercies” takes place during the last sweltering weeks of summer in the run-up to the first day of school. Against the backdrop of busing, “Small Mercies” also contains a crime, which drives much of the action in this riveting, harrowing tale, and helps to lay bare the era’s embedded racism and its corrosive class differences.

Mary Pat Fennessy, a resident of Southie’s public housing, has problems beyond busing. The wages from her two jobs are not keeping up with her gas or electric bills, and her 17-year-old daughter Jules has not returned from a recent night out. The same night Jules did not come home, there was a horrific incident at the Columbia subway station; newspapers reported that some white teens chased a Black teen onto the tracks, resulting in his death.

It turns out the Black teenager was the son of Dreamy Williamson, a fellow healthcare aide at the nursing home where Mary Pat works. Dreamy is one of the few Black people Mary Pat has direct contact with. And even though Mary Pat carries all the prejudices of her neighborhood (“White broads from Southie aren’t friends with Black women from Mattapan”), she likes Dreamy.

Advertisement

Lehane is a rare writer who makes you want to read fast and slow at the same time. His propulsive plots compel you to keep turning pages. Yet, his profoundly perceptive writing makes you want to pause — to laugh at an exquisitely caustic description or to tend the hairline crack a character has just opened in your heart.

Mary Pat is one of those characters. Over the course of the novel, she reconsiders many of her beliefs about herself, her former husband, her neighborhood and her views on race — all the while retaining her fierce nature. She’s ashamed to admit that part of her feelings about Black people is a “grubby desperation” to “feel superior to someone. Anyone.”

She experiences these changes while she’s literally on the move, digging ever deeper into the mystery of her daughter’s disappearance. As the days go by without a word from Jules, Mary Pat asks more and more questions around the neighborhood, stepping into territories closely held by two very different groups: the police investigating the subway crime and the local gang that runs Southie.

The Butler gang, which contains some alarmingly bloodless characters, is so woven into the neighborhood they help residents attend a huge anti-busing rally at Boston City Hall Plaza. This was an actual event, and Lehane vividly portrays all its outsized emotions, from the speakers who whip up the crowd to Senator Ted Kennedy getting shouted off the stage to the anti-busing chants that devolve into ugly racist chants.

But “Small Mercies” is too nuanced a novel to just show the loud surface. So much of the story flows from the maddening powerlessness over their lives that the Southie residents keenly feel. Mary Pat sees the double-frame of school clashes between poor white people and poor Black people while in the suburbs, it’s schoolyear as usual.

This being 1974, the Vietnam War still looms large, and Mary Pat, whose own family was deeply impacted by the war, is well aware that the same Boston neighborhoods that sent the most boys to Vietnam are now the ones clashing about busing. “They keep us fighting among ourselves like dogs for table scraps so we won’t catch them making off with the feast,” she says.

Mary Pat forms a kind of friendship with Detective Bobby Coyne, one of the cops assigned to the subway crime investigation, and whom she’s hoping will help find her daughter. She had hoped that the Butler crew, guys she’s known all her life, would help her find Jules, but she’s met with a surprising silence, which makes her press harder.

Coyne grew up in nearby Dorchester but still considers Southie “unknowable.” In a novel that revolves around the benefits and drawbacks of a tight-knit community, showing Southie from both inside and outside proves very effective. An unlikely duo, Coyne’s and Mary Pat’s conversations provide some of the novel’s most philosophical and bittersweet high points. Coyne is in awe of Mary Pat, who is both “broken but unbreakable.”

Lehane, who grew up in Boston, threads the story with local details that now belong only to history: the afternoon edition of the Herald American, Ned Martin broadcasting Red Sox games on WHDH, Chet Curtis co-anchoring the evening news on WCVB TV. People get groceries at Purity Supreme and buy clothes at Zayre or Jordan Marsh (depending on their income).

But what genuinely gives this novel texture is its language. Lehane is a master at authentic conversation, dialogue that feels like it just exited the mouth of a real person. Given that this is 1974, no one in the novel talks or thinks with any degree of political correctness. The author fully writes out offensive words and descriptions and uses them often, and because of that, the story feels truer.

No one book can contain all of the complexity of the busing years, but with “Small Mercies,” Lehane has opened an illuminating window on one neighborhood caught in one of the most turbulent periods in Boston’s history.