Advertisement

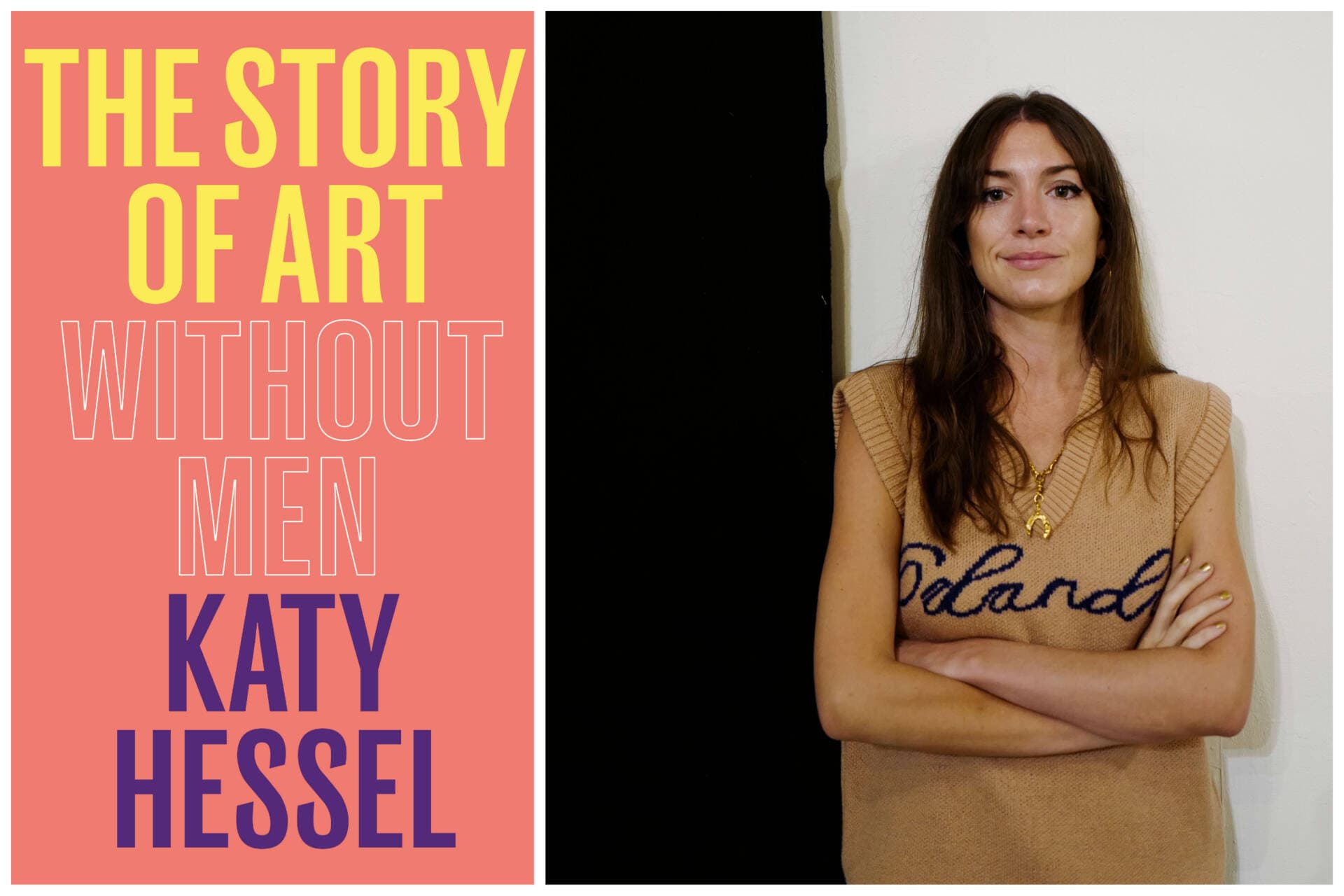

Art historian Katy Hessel shines a light on women left out of the canon

In 2015, British art historian Katy Hessel walked out of an art fair frustrated by what she had seen — or rather, what she hadn’t seen. Out of almost a thousand works of art, she recalls, not a single one was by a woman. Even worse, she realized that she herself was unable to name more than just a handful of women artists, despite her training.

“We go to museums to learn,” Hessel tells me from her home in London. “And if we’re not seeing art from a wide range of people, we’re not seeing society as a whole.”

That night, she created an Instagram account, @thegreatwomenartists, aimed at educating both herself and the wider public about important women in art history. In the years since, she’s expanded into podcasting and has now written a new book that attempts to level the skewed playing field that has left many important women out of the canon and relatively unknown in the broader culture.

“The Story of Art Without Men” (available May 2) is a wide-ranging survey of art history, showcasing the lives and work of women artists from the 16th century to the present in an accessible, easily digestible format.

I had the opportunity to speak with Hessel about several notable women artists whose works are on display at Boston-area museums this spring.

Though the Museum of Fine Arts’ current special exhibit is primarily focused on a male artist, “Hokusai: Inspiration and Influence” (through July 16), also features work from the Edo-period printmaker’s daughter—a favorite of Hessel’s. “I first saw the work of Katsushika Ōi while attending the Hokusai exhibition at the British Museum,” says Hessel, “and I was completely bowled over to discover this determined woman, who was also so instrumental in her father’s career.”

In the book, Hessel writes glowingly of Ōi’s “calligraphic, intricate, and sinuous” line work, and praises her abilities as a storyteller who created “women-led narratives shown through a distinctly female lens” in a period when such things were rarely expressed.

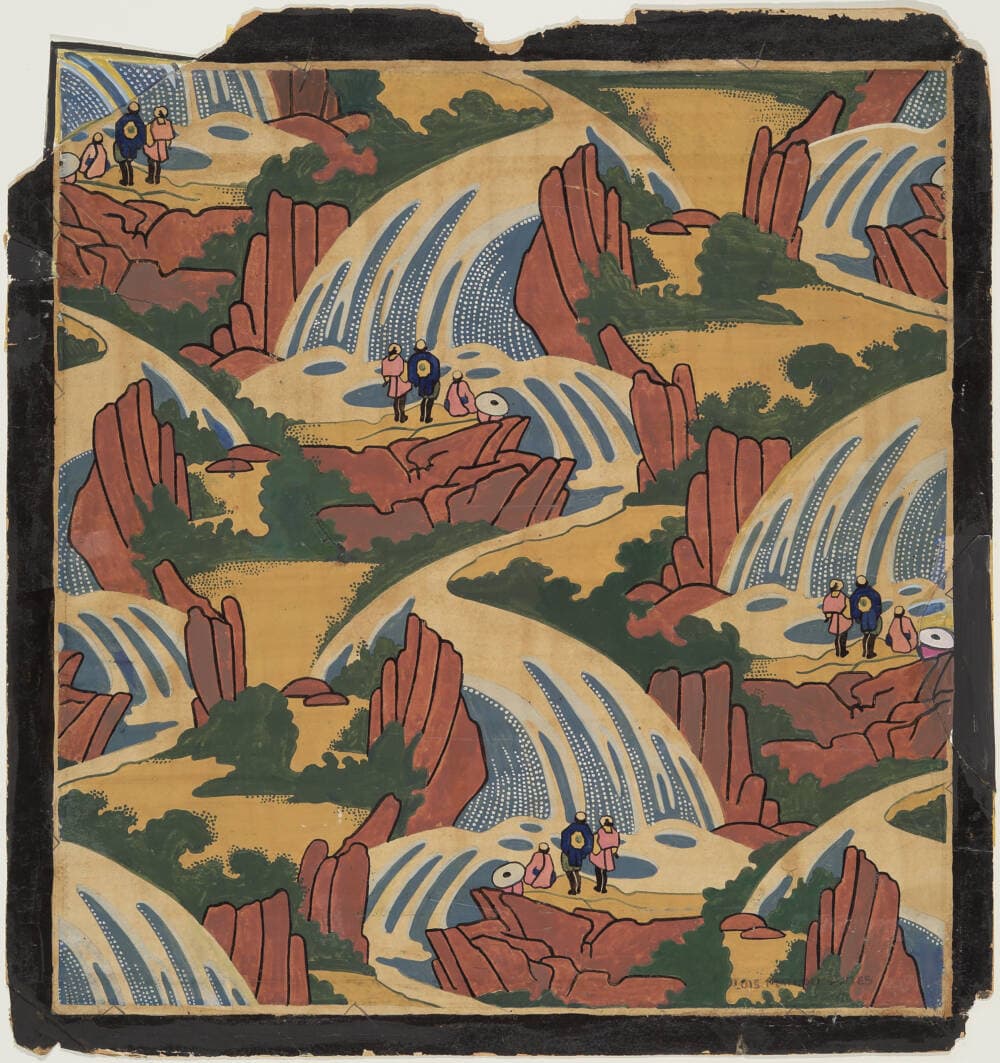

The MFA exhibit also features a Japanese-influenced piece from Boston-born Harlem Renaissance artist Loïs Mailou Jones, though visitors seeking something more representative of her oeuvre will want to swing through the museum’s Saundra B. and William H. Lane Galleries, where they can see several pieces, such as the striking “La Baker,” that provide a clearer, unmediated view of her work.

“Jones had this 70-year career where she lived all around the world — in Paris, in New York City, in Haiti — and she was always drawing inspiration from where she was,” says Hessel. “In the 1930s, she made these beautiful, tender, emotional portraits that honor the beauty of the everyday. But she goes through so many different styles, as well, sometimes verging on abstraction.”

Throughout “The Story of Art Without Men,” Hessel shows how talented women persevered despite being shunted away from more prestigious, male-dominated styles into genres that were considered more appropriate for their gender. “Women pioneered textile art in the 20th century, but their work was dismissed as decorative or craftlike,” says Hessel. “What I try to do in the book is break down the stigma around that, because I want to see these art forms appreciated for what they are.”

She highlights the work of Anni Albers, whose textiles are currently on display in the Harvard Art Museum’s “Artisanal Modernism” exhibit (through May 7). “So much of her work is groundbreaking,” says Hessel. “She made these textiles to be looked at, not for practical use. They’re like a painting in the way the thread glides through the different geometric staves. It’s breathtaking, really.”

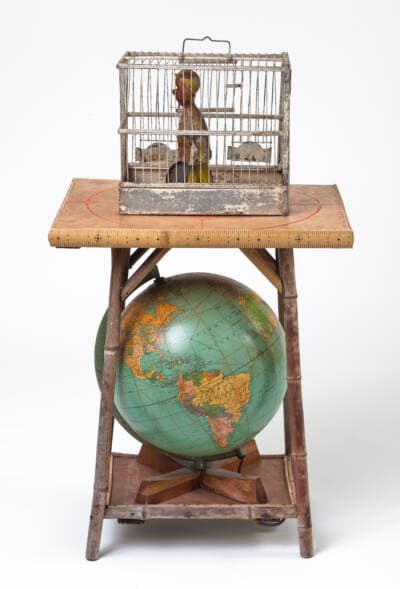

As in Albers’ case, women artists throughout history have often had to make do with whatever resources were available to them. For example, Betye Saar’s assemblage art (on display at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum through May 21) is largely composed of found odds and ends. “She had kids at home,” says Hessel. “She didn’t have access to a giant studio. She used materials that she could take from the kitchen table, which reveals much about her place in society.”

Hessel is quick to note that Saar’s artwork is also fiercely political. Her most famous work, 1972’s “The Liberation of Aunt Jemima,” was a landmark piece, recontextualizing racist depictions of Black women in a way that inspired future women artists of color to seize control of how their stories are told.

This call to action is evident in the contemporary works of Simone Leigh and María Berrío (both on display at the Institute of Contemporary Art through Sept. 4 and Aug. 6, respectively). Leigh, a ceramicist and sculptor, seeks to elevate depictions of Black women through large installations that assert their presence and claim physical space. “What’s so powerful about Simone Leigh’s work is that she works on such a large scale,” says Hessel, “and often in a public realm where her pieces can have an impact. It’s about saying ‘these statues deserve a place,’ and challenging what we’ve always seen about what constitutes a monument or statue.”

Leigh was the first Black woman to represent the U.S. at the prestigious Venice Biennale in 2022, and work from that exhibition will be included in her ICA show. “I remember going to the American pavilion in Venice last year,” says Hessel, “and it was just populated with these very soulful, beautiful sculptures. People were transfixed by it, because it’s taken so long for these narratives to be put up on a pedestal.”

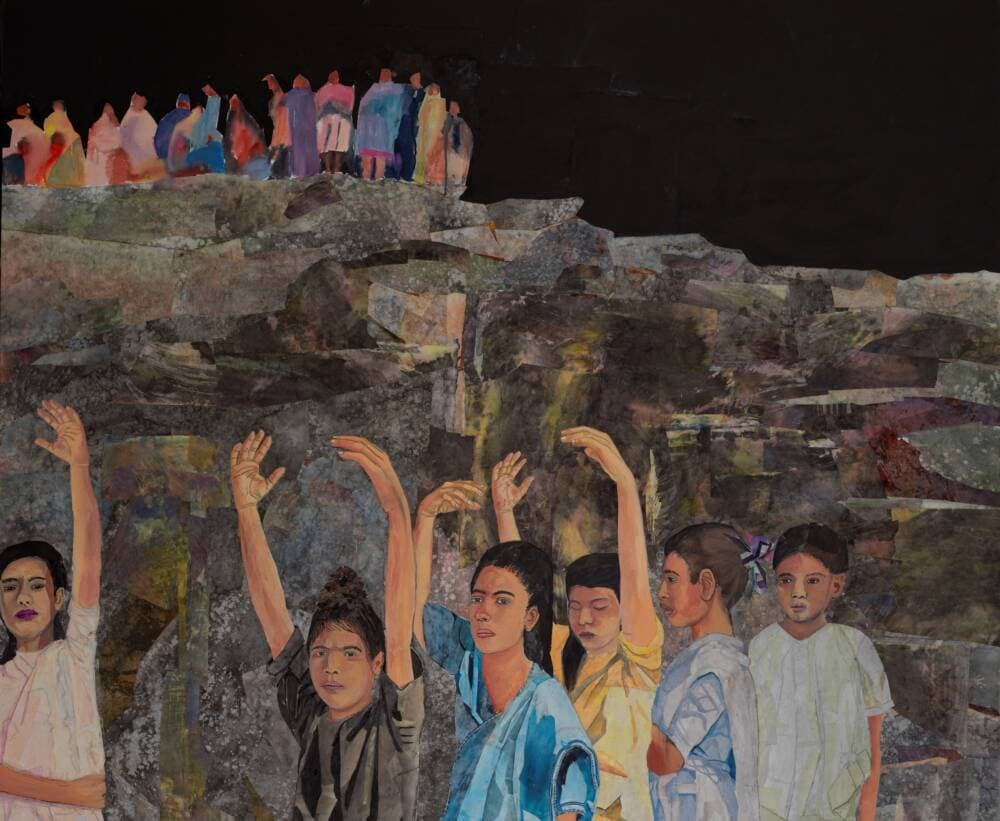

Berrío’s paintings use bright colors and innocent-seeming subject matter to lure viewers closer, where the subtext of her work slowly becomes more apparent. “I think María Berrío is one of the most important artists of our time,” says Hessel. “What’s amazing about her is that she’s fusing myth and folklore with contemporary political narratives,” such as the plight of immigrants and displaced people, ”but in addressing them, she doesn’t prescribe them. I think that’s so much more effective.”

“It looks so beautiful, and then you realize what it is you’re actually looking at. The more you look at it the more sinister it becomes.”

For Hessel, “The Story of Art Without Men” is not just about breaking down the canon in terms of gender, it’s about bringing art history to the mainstream. “I love art history,” she says, “and I want people to see themselves reflected in this amazing subject because I really believe that there is an artwork out there for everyone that can touch them.” With guides like Hessel’s book and exhibitions like these, which feature a diverse array of perspectives, voices, and styles, there may be a greater chance of that happening than ever before.

Katy Hessel’s “The Story of Art Without Men” is out May 2. Hessel will be speaking at the Museum of Fine Arts on Friday, May 5.