Advertisement

Review

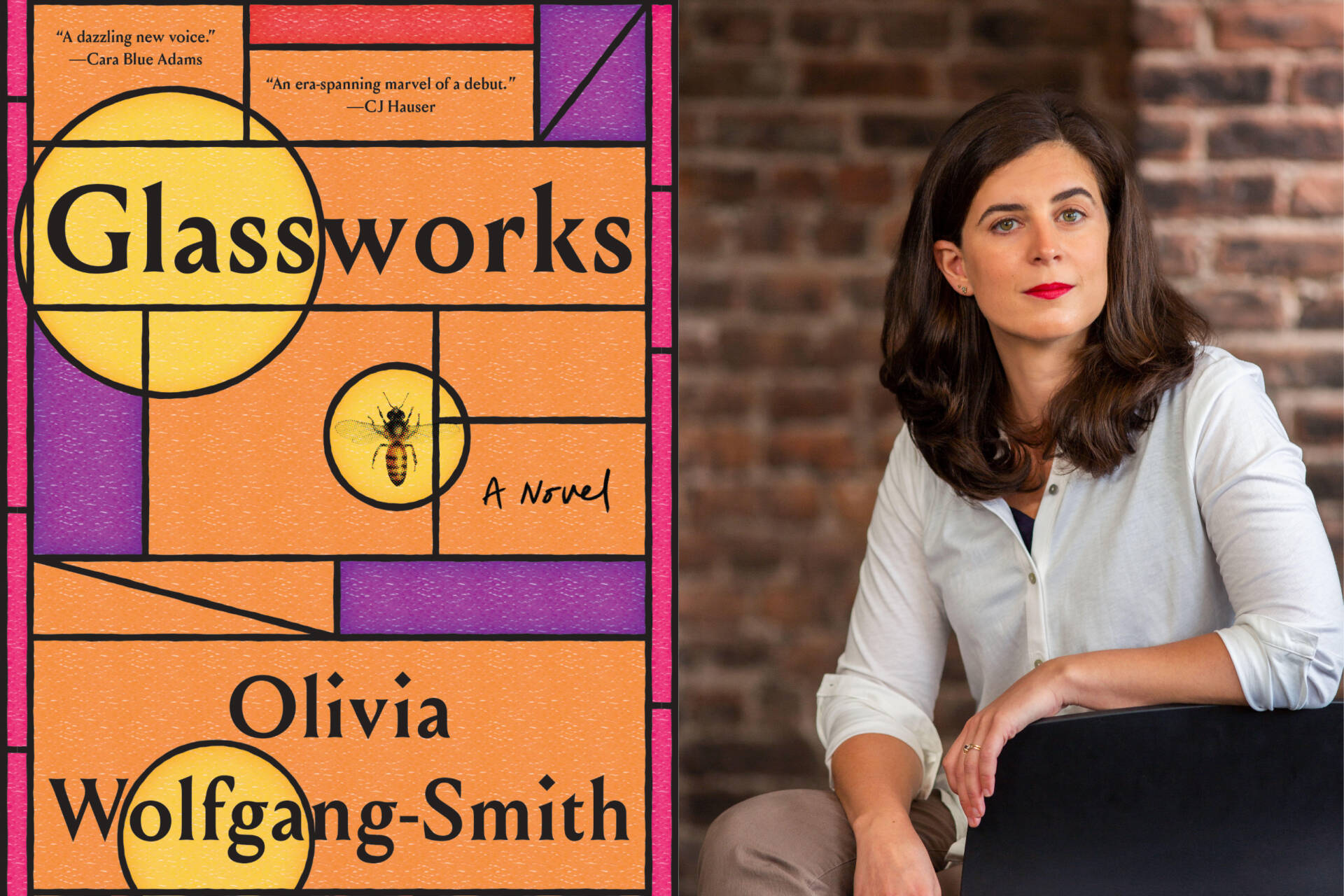

New novel 'Glassworks' explores a century's worth of needy and unpredictable love

In her debut novel “Glassworks,” Olivia Wolfgang-Smith explores the fallout from flawed versions of love: love that is needy or unpredictable or simply withheld. The author’s linking of different characters in this multigenerational tale takes on many forms, including glass. The novel abounds with descriptions of intricately constructed glass models of flora and fauna, stained glass windows whose colors shift with the hours and miles of reflecting panes in New York City skyscrapers.

Although the storyline thins out part way through, Wolfgang-Smith’s writing — a heady blend of rich descriptions and discerning insights — makes this novel a striking read.

“Glassworks” takes place primarily in Boston and New York City, spanning the years from 1910 to 2015. That’s a lot of ground to cover, and the book is divided into four large sections, each occurring decades after the previous one.

In turn-of-the-last-century Boston, Agnes Carter is a socialite from a prominent family and a trustee on the board of an unnamed Massachusetts university that looks an awful lot like Harvard, especially its Museum of Natural History. The board has commissioned Ignace Novak, a world-renowned naturalist and glass modeler, to create hundreds of glass figures of flowers, fruit and sea creatures, “so that undergraduates might study species rendered inaccessible by season or geography.” His creations are so finely wrought that they’re often mistaken for the real thing.

For Ignace’s work, Wolfgang-Smith incorporates notable aspects of glass blowing and the drawings on which they are based. Even when a drawing is grotesque, like a squashed bee or a rotting piece of fruit, there’s a dreadful beauty in the care used to create the image. In fact, for each era highlighted in this novel, there is an appealing bounty of information on each main character’s profession: the patient virtuosity needed for impeccable glassmaking, the complexities of window washing at dizzying heights, the multi-faceted art of a Broadway production.

Agnes’ board position is not an empty honor. Her education includes botany and Latin, and she yearns to accomplish much more than women of her time are allowed. Thinking a marriage of convenience will gain her more freedom, Agnes makes a disastrous choice of husband. Soon after, she falls hard for Ignace, the eccentric genius who shares her passion for science and art. Enough drama ensues that Agnes and Ignace vow never to return to Boston.

Advertisement

When we next meet them in 1938, they are the world’s premiere married couple of science. They’re also the disengaged parents of nineteen-year-old Edward, a lonely, lost young man who has always been shut out by his parents’ self-absorbed love. Edward dreams not of science but of religion (he imagines ecclesiastical life as one of “unconditional love”). When that doesn’t pan out, Edward gets a job at a stained-glass company in, of all places, Boston, which he hopes will at least bring him a little closer to God.

Agnes won’t visit Edward, but she does send him a gift of a small glass bee from one of Ignace’s flower models. It will be passed down again and again, often haphazardly, with most recipients having no idea of its story or its monetary value.

Just as it’s impossible to create a masterpiece without all the right materials, successive generations in “Glassworks” flounder without full knowledge of their family’s past or some foundational nurturing love. Kids grow into adults first as afterthoughts, then as caretakers, to their disengaged parents.

Edward’s job proves more frustrating than fulfilling (he often thinks, comically, that God only hears half his prayers, as if he “and God had a poor telephone connection”). Yet it does place him in the path of the dazzling, gin-drinking Charlotte Callahan, whose family, with their rowdy Sunday dinners and easy camaraderie, is everything Edward’s is not. But, as with his own family, the Callahans have secrets.

Fast forward to 1980s New York City during the AIDS crisis. Edward and Charlotte’s adult daughter Novak, a window washer of the city’s skyscrapers, struggles to physically care for the now-feeble Edward. She also often plays emotional counselor to her friend Felix, who is in an abusive relationship.

Novak, who is gay, knows, just as she must be attuned to her environment when she’s working many stories above the pavement, that being gay at that moment in New York means “noticing necklines, haircuts, lesions, hands.” And Novak is always alert to when she is being noticed — in a friendly or menacing way.

So much of “Glassworks” is about noticing; pages are redolent with sound, scent and color. Take, for example, how Wolfgang-Smith describes the lived-in atmosphere of Ignace’s studio: “After the clear fall sunlight, the studio felt like the inside of a pocket, a musty darkness smelling of soot and varnish and unwashed scalp.” Or the unique combination of scents in a church, “The transom windows were cracked; a lilac-perfumed breeze mingled with the plush sacred air of the chapel.”

Reluctantly accompanying Felix to a matinee, she is struck by Cecily, a young dancer onstage who plays male and female roles equally well. There’s a spark, not of romance, but a common bond. Novak responds the only way she knows how. She’s convinced Cecily needs her protection and guidance and will risk anything to accomplish this.

Jump to 2015, and Cecily’s adult twin daughters, Tabitha (successful professionally and romantically) and Flip (decidedly not), are living in Cambridge and Boston. Like those before her, Cecily is a disconnected parent who shares nothing about her past. Her Broadway friends from the eighties are viewed by her daughters as quirky characters. These once-primary personalities are reduced to present-day shadowy figures, with only you, the reader, knowing their full story.

Desperate for any new job that will cover her rent and her weed habit, Flip begins working at a glass studio that puts cremains into glass ornaments. It’s a random choice that, like those of other key characters, may prove fateful.

Although part of the novel’s later sections read more like set pieces than fully formed chapters, Wolfgang-Smith’s originality in terms of themes and settings, and her well-honed literary craft, make you look forward to what this talented author will write next.