Advertisement

The unexpected story of how the birth control pill was invented and tested

The birth control pill traces its origins to an unexpected place: an infertility clinic.

It all started in the 1950s with an odd scientific couple, two Massachusetts men known for their expertise in reproduction — not the opposite.

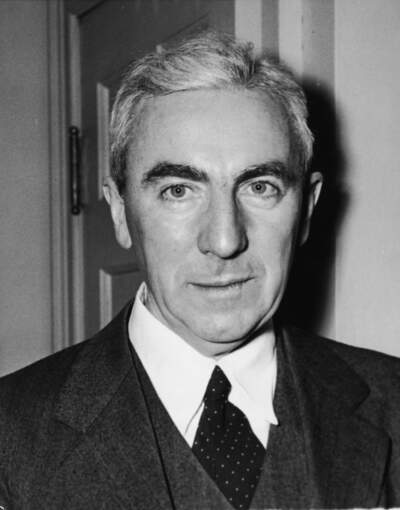

John Rock was a devout Catholic who ran a renowned clinic in Brookline for patients who were having difficulty getting pregnant. Gregory Pincus was a biologist who gained notoriety after performing in vitro fertilization in a rabbit. At the time, the idea of using outside intervention to create a new life was highly contentious.

By 1960, Rock and Pincus would become famous for creating the first oral contraceptives. But first, they had to develop and test this innovation, which has since been used by hundreds of millions of women around the world.

Drug regulators are currently considering whether to make a birth control pill available over the counter in the U.S. This milestone has prompted some historians and advocates to revisit the pill's quirky and controversial beginnings.

Discovery in Massachusetts

Women came from around the world to see Rock, a Harvard-trained gynecologist and obstetrician, at his clinic.

“It was the baby boom and they wanted desperately to be pregnant,” said Margaret Marsh, a historian of reproductive medicine at Rutgers University.

Rock had a theory that his patients were struggling to conceive because of what he called an “underdeveloped” reproductive system. He planned to give them hormones theorizing the treatment would let their systems rest and then restart.

Back then, there was little in the way of research ethics and patients often had no idea they were part of an experiment. But Rock did things differently for the 80 women he enlisted in his trial.

“He was a real unicorn,” said Marsh. “He never asked women to be part of a research study unless he explained to them everything that was going on.”

Not far away, Pincus was conducting his own research out of a converted carriage house in Shrewsbury. His work on in vitro fertilization was a scientific breakthrough, but it was so contentious that many historians believe it helped cost him tenure at Harvard.

As he rebuilt his career, he received support from prominent feminists, including Margaret Sanger, the founder of Planned Parenthood, and philanthropist Katharine Dexter McCormick. Their directive: develop an oral contraceptive.

Advertisement

Pincus hired doctors to experiment on women — and men, too — at a state mental hospital. Using methods that were common at the time, he didn’t tell the patients what he was doing, although he did get consent from their families.

Pincus and Rock differed in how they approached patients, but they were working with the same hormones, and before long, they decided to team up. Looking at uterine tissue from Rock’s patients, they realized none of the women were ovulating. They concluded that the hormones could act as birth control.

There was just one problem, Marsh explained: “In Massachusetts during this time, birth control was prohibited. It was against the law.”

Controversy in Puerto Rico

Pincus and Rock scrambled to figure out where to conduct a bigger trial. In letters between the researchers and their patrons, they considered Japan and Hawaii. But, the men ended up heading south to Puerto Rico, which was already a U.S. territory.

A key factor in selecting Puerto Rico was the fact that birth control was legal there, and had been since the late 1930s, said Marsh. Plus, the researchers had medical colleagues on the island, and many of the doctors there had been trained in the U.S.

Although birth control was legal, the trial was immediately contentious.

“Before anybody swallowed the pill, there was controversy,” said Marsh.

The Catholic Church was a vocal opponent, remembered Edris Rice-Wray, the doctor in Puerto Rico who ran Pincus and Rock’s trial.

“The priest would denounce the method we were using in the pulpit, and then the women would run in the next day and say, ‘What is it the priest said we couldn’t have?’ ” said Rice-Wray in an oral history recorded before her death, which is now part of Smith College's special collections.

“We couldn't get enough pills because, as soon as we got started, everybody wanted to get on it,” Rice-Wray remembered.

About 800 women signed up to take the pills. Many of them lived in a nearby housing project.

It is not clear whether these women were told this new medication was still experimental. What is known is that three women died, although no investigations of their deaths were conducted.

The dose the women were given was many times higher than birth control pills today. That caused many of the women to experience severe side effects, including nausea, dizziness and headaches. But Pincus dismissed their symptoms.

“They even said that many of the effects were psychological because we Puerto Rican women are hyperactive emotionally,” said Lourdes Lugo-Ortiz, a professor at the University of Puerto Rico.

Pincus was dismissive because he didn’t want anything to stand in the way of the drug’s success, according to Lugo-Ortiz. And he appeared convinced the drug was safe, explained Marsh.

“Their claim was that Puerto Rico was used as a testing site, that we were guinea pigs."

Lourdes Lugo-Ortiz

“He was handing it out like candy to his female relatives. He was not seeking to foist on a population of women, who were women of color and poor women, something that he didn't believe was safe,” said Marsh. “That said, it was still a controversial trial.”

In Puerto Rico, politicians, newspaper columnists, and others took a stand against it.

“Their claim was that Puerto Rico was used as a testing site, that we were guinea pigs," said Lugo-Ortiz. "Our women ... are abused by the U.S. imperialism.”

Despite the concerns, the study went forward, and the data gathered in Puerto Rico changed the lives of millions of women around the world.

The first 'lifestyle drug'

Just as the trials were controversial, so was the Food and Drug Administration’s approval process for the pill in 1960, said Marsh.

It was the first so-called “lifestyle drug” approved by the FDA, meaning it was a medication that does not treat a medical condition.

“It is a drug that allows women to control completely — all by themselves — when they are going to become pregnant.”

Margaret Marsh

“It is a drug that allows women to control completely — all by themselves — when they are going to become pregnant,” said Marsh, adding that this idea was unsettling for many people at the time.

But, the birth control pill was immediately and immensely popular. Within a few years, millions were taking it daily. Yet not everyone had access to the pill even after the FDA approval.

In Massachusetts and many other states, the birth control pill remained illegal until the U.S. The Supreme Court gave married couples the right to use contraceptives in 1965.

The 'Free the Pill' campaign

Today, the pill is available without a prescription in more than 100 countries — but not in the U.S.

For nearly 20 years, a team of researchers, activists and doctors has worked to make the pill available over the counter. They argue the need for a prescription creates an unnecessary barrier for people who have limited resources or difficulty accessing a medical provider. These advocates say the pill’s fraught history has shaped their efforts.

“We needed to really reckon with and explore the history of harm and oppression in the development of the pill itself,” said Kelly Blanchard, who heads Ibis Reproductive Health, a nonprofit research group that spearheaded the "Free the Pill" campaign.

Belle Taylor-McGhee, an activist who has been involved since shortly after the effort launched in 2004, said reproductive justice activists have played an important role in the effort. “Not only did we have voices at the table, we brought people on as members of the steering committee,” she said.

While there has not been widespread political opposition to offering the pill without a prescription, the move is opposed by the Catholic Church. In addition, some debate has centered around age restrictions on over-the-counter birth control.

Earlier this month, the FDA’s advisory panel unanimously recommended making the switch away from a prescription drug. The FDA is expected to make a final decision this summer about whether to make the pill available over the counter in the U.S. — including in Puerto Rico and Massachusetts, the communities where it was first researched and tested.

This segment aired on May 24, 2023.