Advertisement

Patients, doctor say closing of Emerson Hospital addiction medication program worsens 'treatment desert'

Patients from an outpatient medication addiction treatment program run by Emerson Hospital in Concord have to go elsewhere for that care.

Emerson Health, which operates the hospital, shut down the program Friday, only a few years after it opened.

Hospital officials said they're shifting priorities. But patients, advocates and the doctor who ran the program say the area of the state it served lacks medication treatment programs for substance use disorders and that the closing harms people who need that care.

One of the patients who used the Emerson program is Joey Kinghorn. At a recent appointment, the 37-year-old told his addiction medicine physician, psychiatrist Dr. Stephanie Stratigos, that he was in good spirits and his medication was working well; he had no cravings or urges to use opioids.

Kinghorn said he became addicted to OxyContin in 2005 after he broke his foot. He was able to stop taking the pills on his own back then. But in 2019, he said, doctors prescribed the painkiller again after a procedure. He fell deep into his addiction and started buying drugs off the street.

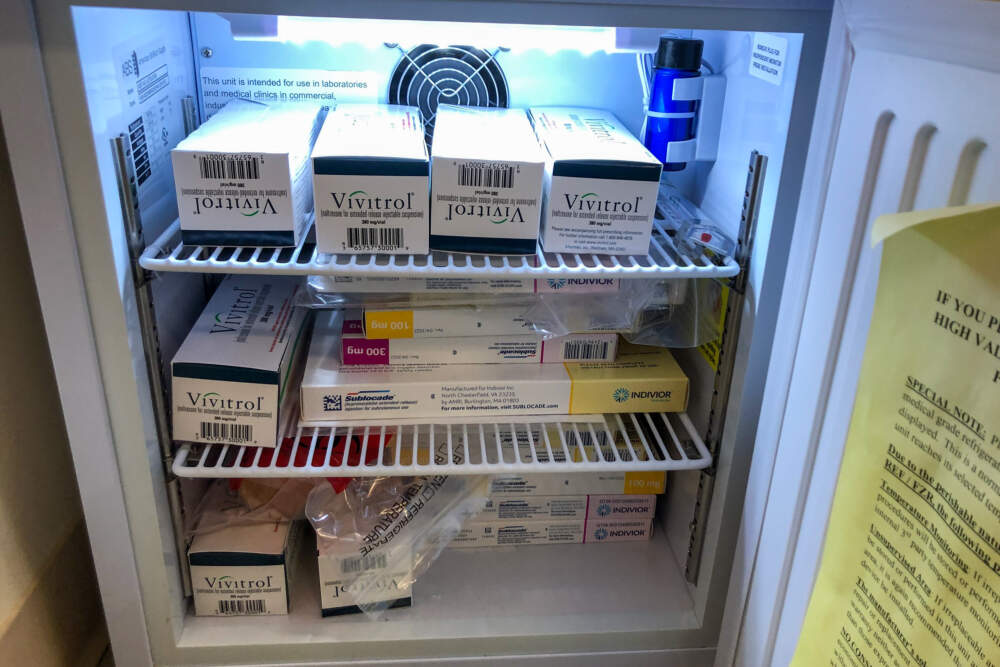

About a year later, an online search led him to the Emerson clinic, which was located in an old colonial-style house on hospital grounds. At first, Stratigos prescribed Suboxone for him. That's the daily oral form of the medication buprenorphine, which is considered a gold standard to treat opioid use disorder. But then she switched him to a monthly injection of Sublocade, the extended-release form of the medication.

“It’s done wonders for me. It literally saved my life," Kinghorn said.

Costs and demand

In addition to the clinic in Concord, Stratigos ran one out of an Emerson medical building in Groton; that one has also been shut down. Stratigos, who was terminated by Emerson with the ending of the program, prescribed medications for drug, alcohol and nicotine addictions at both facilities. The Groton clinic was initially funded by a federal grant responding to the rate of opioid overdoses in neighboring communities.

“We sat on a big coalition of people in the region to figure out what would be a meaningful intervention and how to save lives in that area," Stratigos said. "And it did measurably save lives.”

The program served a swath of suburban towns along the Route 2 corridor, including Acton and Littleton, and rural towns moving northwest through Middlesex County, including Pepperell and Townsend.

After WBUR's inquiries about the shutdown, Emerson released a statement from Dr. Barry Kitch, senior vice president of clinical affairs and chief medical officer for Emerson Health. Kitch said medication treatment for substance use disorders is more accessible than it was when Emerson started the program in 2019 — through telehealth, primary care, specialty providers and free-standing programs. As a result, he said, Emerson is focusing on emergency and inpatient behavioral health care. (Patients can be started on Suboxone in those units, then the treatment must be prescribed by an outside provider.)

Kitch also said a "limited number" of patients were seen in the outpatient treatment program — not enough to maintain the service in challenging post-pandemic economic conditions.

Advertisement

Documents provided by the state health department show the area has no other outpatient medication treatment programs for opioid use disorder (there is one program in Ayer that provides medication treatment to veterans).

Stratigos said she kept a full schedule, seeing hundreds of patients through the Emerson program.

The program cut comes as Massachusetts is still in the throes of an opioid epidemic. State data show overdose deaths reached an all-time high in 2021. The death rate may have declined slightly in the first nine months of 2022, according to preliminary data. The Department of Public Health said it plans to release data for all of 2022 this month.

Concern about the treatment program’s future started a year ago. According to internal emails and documents Stratigos shared with WBUR, the hospital's finance department said the program was losing money. Stratigos questioned the numbers, and she offered to work with the hospital to increase revenue from insurance reimbursements if necessary. But after some communication about exploring that possibility, she said, hospital management made it official early this year that they would end the program.

Stratigos claims the program's direct operating expenses were much lower than the hospital had documented, and she thinks the program never should have been on the chopping block.

“It doesn't make sense for the amount of good that the service does for the hospital, for the community, for the patients,” she said.

A 'treatment desert'

Emerson Health declined WBUR's requests for interviews with the CEO, chief medical officer and chief financial officer, and it did not answer several of our questions. The hospital's statement did not respond to Stratigos' claims about the program's cost.

In the statement, Kitch said Emerson Health has a “long-standing commitment to support patients with behavioral health needs, including those addressing the challenge of addiction.”

But according to Stratigos, Emerson's move will make getting care harder for many people, who will have to go further for treatment – to cities including Boston, Lowell and Leominster.

“The more barriers you put in place, the less people are going to engage in this treatment," Stratigos said. "You have to make it really, really easy to get care in order for the care to be effective.”

One of the people who helped lead the grant-funded effort that led to the Groton clinic is Susan Buchholz. She came to that work as co-chair of the grassroots Joint Coalition on Health, which advocates for more access to resources for vulnerable populations in north central Massachusetts. Buchholz said Emerson's termination of Stratigos and shutdown of the program hurts people in the region, which she calls a "treatment desert."

“These are people who were just desperate for services," Buchholz said. "They are in Emerson’s back yard, and the fact that her facility grew so quickly with the number of patients is just evidence of how much unmet need existed in that area."

Buchholz said developing a relationship with a provider is extremely important for people in recovery. Research has found that people stick with treatment longer when they receive it from a provider who is geographically close to them.

“The more barriers you put in place, the less people are going to engage in this treatment. ... You have to make it really, really easy to get care in order for the care to be effective."

Dr. Stephanie Stratigos

Joey Kinghorn and another patient who's been undergoing treatment at the Emerson clinic in Concord, who is also named Joe, said they've built that kind of connection with Stratigos.

"When I first started treatment with her, she would check in fairly regularly ... and just make sure everything was OK," Joe said. "And she was very much interested in the actual recovery."

Joe asked to only use his first name, for fear of future job discrimination. He said he’s stable on the treatment he’s been getting from Stratigos. But he worries about others looking for help – people still in the throes of their addictions, who don’t have stable jobs like him and employers who will be understanding when they have to drive 30 minutes or more to get their addiction medication.

"You lose your job. You get depressed. What do you do? You want to go get high," said Joe, who took part in a protest outside Emerson Hospital in February to try to save the program. "Why would you take out the one [medication treatment program] in this area? … I love Emerson Hospital. I don’t understand why they’re trying to turn away from this community. It just doesn’t make sense. The need is here.”

Missing the other end of the 'bridge'

According to Stratigos, despite the good the program did, some patients should have gotten even more help from Emerson Health. The program was meant to be a "bridge clinic," she said. She would see patients quickly and stabilize them for several months with medication. Then their primary care doctors would take over their addiction treatment.

But that’s not what happened. Stratigos — and two other Emerson Health employees who don't want to be identified for fear of retribution — said the administrators of Emerson’s primary care network supported that approach, but that for the most part, the primary care doctors adamantly opposed it — with some expressing that they weren't comfortable prescribing the medication. They said that out of 60 Emerson primary care physicians, only a few got licensed, or waivered, to prescribe buprenorphine (a license that's no longer required by the government as of this year).

WBUR asked to speak with the president of Emerson Practice Associates — the primary care network — but Emerson Health declined our request.

The reluctance among many physicians to provide addiction treatment stems at least partly from a historic lack of training on addiction in many medical schools and residencies, according to Dr. Sarah Wakeman, a national expert on addiction medicine. Wakeman is a primary care and addiction medicine physician who heads substance use disorder programs at another health care system — Mass. General Brigham. MGB operates four bridge clinics for quick-access medication treatment for substance use disorders and provides the treatment at some of its primary care practices.

Wakeman said she doesn’t have insight into the closing of the Emerson program. But, she said, in order to eliminate gaps in access to medication treatment for addiction, the medical community has to stop viewing it as different from the rest of medical care.

“The more we can embed this … as a component of primary care and hospital-based care, the better we're going to be able to serve patients who are already there, already have established relationships and should be able to access their addiction treatment wherever they get the rest of their medical care," Wakeman said. "I would say, one, this is simpler than so much of what we do, but most importantly ... that you can really be a part of actually saving people's lives amidst the worst public health crisis from drug overdose that this country has ever seen."

Where patients go from here

Emerson said it’s arranged for all patients to have seamless access to treatment and that no patient will be left without care.

According to Stratigos, that’s because she accepted a job at a program in Leominster – more than 20 miles west of Emerson – where she’s allowed to transfer her patients.

She said the majority of her nearly 230 remaining patients are going with her — including Joey Kinghorn. He’ll have to travel a little further from his home in Littleton. And he’s legally blind, so getting to treatment isn’t easy to begin with.

“My parents are going to have to sacrifice their time to get me there," Kinghorn said.

Stratigos and community advocates said they worry about how the change will affect current and future patients who face even bigger transportation barriers. Some don't have cars or have lost their licenses due to their addictions, and any disruption can reduce the chance of recovery.

This segment aired on June 8, 2023.