Why hundreds of thousands of poor, disabled children are missing out on federal help

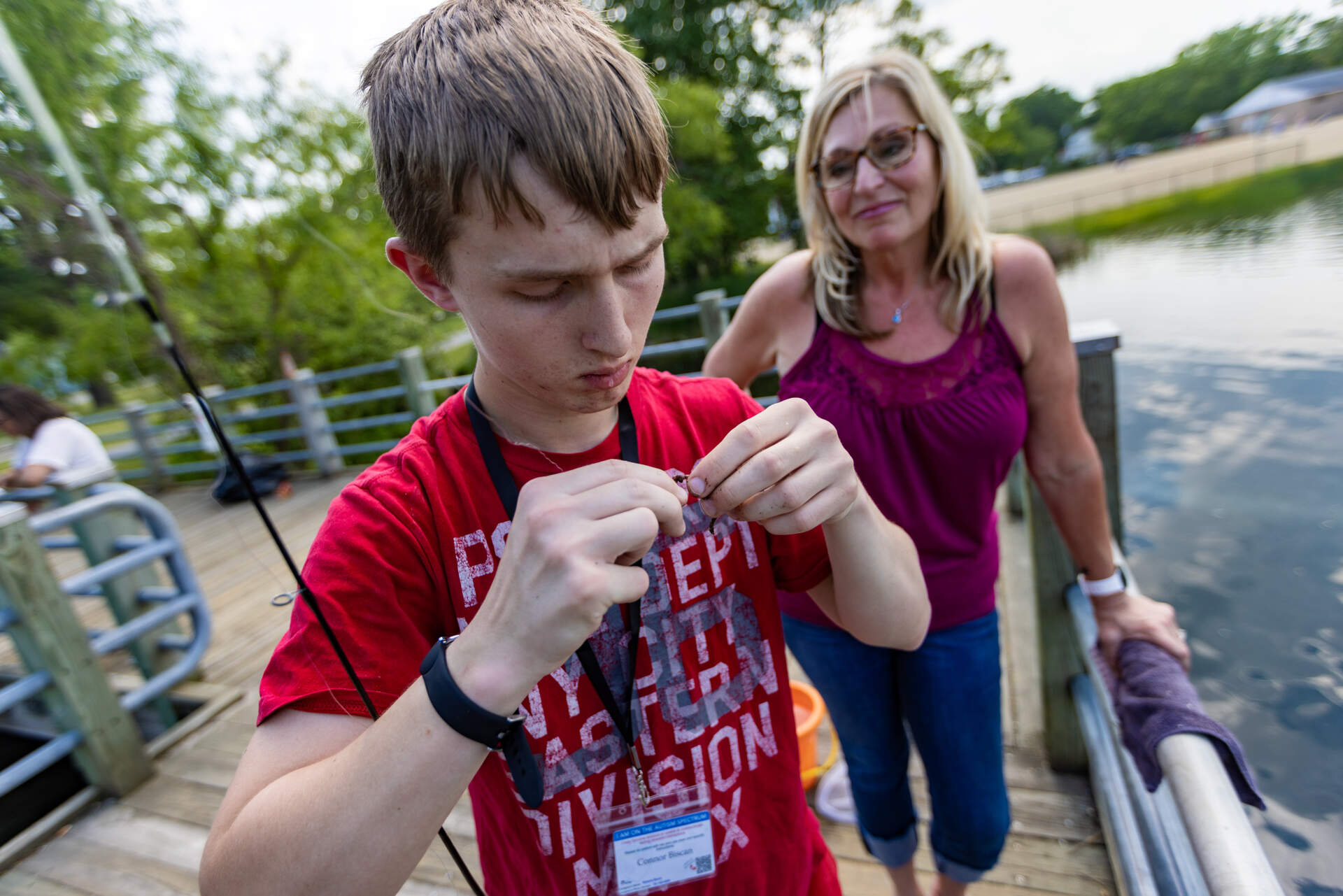

The closet under the stairs is Connor Biscan’s favorite place to hang out at his family’s home in Wilmington, Massachusetts. It’s filled with oversized stuffed animals, big balls and other items that bring him comfort.

As a toddler, Connor would open and close cabinets repeatedly, screw and unscrew water bottle caps. His mother, Roberta Biscan, watched him carefully. It wasn't long before Connor was diagnosed with autism.

Biscan remembers feeling an overwhelming sense of sadness and despair. One big concern was financial. She'd held a customer service job for more than a decade, and as a single parent to her son and newborn twins, she'd always planned on working. But, soon after Connor’s diagnosis, she realized she needed to quit.

“I couldn't work for the first 10 years of his life because I was just so busy with therapy appointments [and] doctor's appointments,” Biscan recalled. “I just had to be available.”

Biscan regularly stayed up until the early morning hours searching for resources to help her family get by.

One night she stumbled on what would become their lifeline: Supplemental Security Income or SSI.

The federal safety net program serves people who are very poor, and who have a disability or are elderly. About a million of America’s most vulnerable children receive money through SSI and, in many states, receiving SSI qualifies them for health insurance under Medicaid. One report estimated that the program lifts about half of its child beneficiaries out of poverty.

Connor’s disability, plus his family’s limited income, qualified him for about $500 a month. “That money was really important so that I could give him some shelter, food and clothing,” Biscan said.

But, Biscan would learn, the lifeline was a fragile one.

Over the past decade, the number of kids getting SSI benefits dropped dramatically. Experts estimate there are hundreds of thousands of children not getting the help they are eligible to receive.

Connor, who is now a teenager, is among those who have suddenly fallen off the rolls.

Losing benefits can harm children and their families. Families are more likely to experience financial hardships, and there is evidence that when young people lose SSI benefits they are more likely to commit crimes to make up for the lost income. Academics, advocates and administrators are grappling with why SSI enrollment has declined and what to do about it.

'All-time lows'

SSI was born out of an attempt by the Nixon administration to overhaul the nation’s welfare system and offer money to poor, working families. When that plan failed, the federal government created SSI in 1972 as a more limited welfare program.

"Fifty years ago, at the beginning, almost no children qualified,” said Kathleen Romig, director of Social Security and Disability Policy at the nonpartisan Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “That changed in 1990. There was a Supreme Court case that said using the adult standard of disability for children didn't make sense and that there should be a separate child standard.”

Soon after the court's decision, the number of children receiving SSI benefits began ticking upward. Yet, SSI has never reached all the children who are eligible. Experts see big variations in enrollment from one county to the next. And there are variations by disability.

One report estimated that less than 5% of children with depression who would likely qualify for SSI received the benefits. Yet, about 50% of similar kids with autism were enrolled. Policy experts have found that personal networks and advocacy groups play an important role in alerting parents to the program.

Advertisement

Even with the disparities, 50 years into the program’s tenure, SSI sends out nearly $60 billion in payments annually to about 7.5 million people, including approximately a million children.

But Romig and other experts have noticed a striking trend in recent years: The number of children getting help from SSI is falling.

“Enrollment has declined," said Romig. "In fact, in the last few years, SSI enrollment has reached all-time lows per capita."

While enrollment for older adults in the SSI program has recently begun to rebound, that’s not true for kids. The number of children enrolled has dropped more than 20% over the course of a decade, and applications are down by about 50%, according to the most recent annual report by the Social Security Administration, which runs the program.

The termination letter

In 2013, Connor began attending a residential school that offers more structure and helps manage the challenges he experiences as a result of his autism.

Soon after he moved schools, Connor's mom resumed working. She diligently reported her income to SSI and saw Connor’s benefits reduced accordingly. Still, she said, the remaining money was key to enabling Connor to sign up for enrichment activities and get sensory tools that aid his development, as well as maintaining the family's home, which Connor visits on weekends.

More than a decade after Connor enrolled in SSI, Biscan arrived home to find a letter.

“I opened it and I read it, and my jaw dropped,” she remembered.

Connor’s SSI benefits had been terminated. Another letter said she needed to repay many thousands of dollars the family had previously received in benefits.

Biscan’s best guess is that a bit of financial information was misrecorded. In the months and years that followed, Biscan tried desperately to fix the problem. She emailed, faxed and called the SSI program.

“No call back, no acknowledgment,” she said. “It's absolutely a nightmare.”

She worked with disability advocates and contacted local politicians for help. Without SSI, she said, she's had difficulty paying her utility bills and had to pull Connor from some recreational activities. After three years trying to resolve the situation, she said, it’s still not fixed.

The Social Security Administration declined to discuss individual cases, but said in a statement, "We are focused on addressing our challenges, and our employees are working hard to serve the public." The agency acknowledged that funding has been an issue. "For over a decade SSA received insufficient funding from Congress to administer its programs," the statement said.

Parents report a range of frustrations.

Deborah Harris, of Maryland, said SSI threatened to cut off her grandson’s benefits because staff had not received all of his paperwork. She maintains the documents were sent and received. “I’d taken the time to go get certified mail," she said. "So somebody had to sign for that.”

“You're told where to go but instead of being given a 10-speed bike, you're given a tricycle with two wheels.”

Terri Farrell

Alicia Thomas, of Boston, said whenever she mails a document to SSI she is “praying it gets scanned on the right side because, unfortunately, sometimes they scan it on the opposite [blank] side,” and the information is never recorded.

SSI does provide drop boxes at its field offices as an alternative to mail, but some applicants have faced similar frustrations depositing documents there. “They go into an abyss,” said Thomas, who has spent years navigating SSI on behalf of her son. “It’s like washing socks in the washing machine. You put two socks in, but you never find them both.”

Terri Farrell, of Lynnfield, Massachusetts, applied for SSI on behalf of her son. She described the effort as "Herculean."

“You're told where to go but instead of being given a 10-speed bike, you're given a tricycle with two wheels,” she said.

Advocates said the experiences of Biscan, Harris, Thomas and Farrell have become the norm.

“There was a time in the '80s and '90s when you would just get the records and show up, and things worked the way they should work, right? These days, it is so incredibly tough,” said Taramattie Doucette, co-founder of the Children's Disability Project at Greater Boston Legal Services. “We are genuinely surprised when we get a client who says, ‘Oh, everything worked well.’ ”

The concerns of parents and advocates have reached Washington, D.C. Sen. Ron Wyden, a Democrat from Oregon, has a term for the SSI frustrations he hears about: “bureaucratic water torture.”

The front door and the exit

While dealing with a federal bureaucracy is frustrating, it may be just one piece of the puzzle. There are a number of factors contributing to the steep decline in kids applying for and receiving SSI benefits.

The Social Security Administration pointed to a drop in birth rates as one explanation, along with a stronger economy after the Great Recession and changes to federal law that have provided health insurance for more families. The agency also said COVID played a role. Applications for SSI dropped precipitously when the pandemic shuttered field offices for two years.

Those explanations contribute to the shift, but experts said they don’t explain it all.

One of the biggest issues is money, specifically the budget of the Social Security Administration, according to Romig of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Between 2010 and 2023, she calculated the agency's customer service budget fell 17% after accounting for inflation, and staffing fell 16%. Last year, the agency reported staffing reached the lowest level in 25 years.

Fewer employees is a problem because families must work with a social security representative to apply for SSI benefits on behalf of a kid. With a shrinking staff, “it's been very difficult to get an appointment,” Romig said.

So, it's hard to get in the front door. At the same time, families enrolled in the program are increasingly shown the exit.

When people get kicked off the program, it’s often part of a process called "continuing disability reviews." That’s when SSI staff check to make sure people still qualify for benefits.

For a while, SSI had very limited funding to do these checks, said David Wittenburg, a senior fellow at Mathematica, a social policy research and analytics group. “And then they got administrative funding in 2015 and did a lot of continuing disability reviews,” he said.

While the funding to help people enroll in the program has dropped, Wittenberg said, the process that removes people from SSI is well-funded.

He said sometimes it makes sense to take people off SSI — if their disability got better or they began to earn more money, for example. But sometimes it’s because of a mistake.

“If you submit the wrong paperwork or if you don't file on time, you lose benefits,” he said. And research has shown when young people lose SSI benefits, the consequences can be serious.

'Turning to illicit activity'

Manasi Deshpande, an economist at the University of Chicago, studied two similar groups of 18-year-olds starting in the mid-1990s. One group was just old enough to avoid a new review process and kept their benefits. The other group lost benefits.

After following the same people for decades, Deshpande concluded that when young people were removed from SSI, "a lot of them [were] turning to illicit activity."

“And that is then increasing the likelihood that they spend time in prison,” she said.

For the young people whose checks were cut off, she found a 60% increase in criminal charges — for nonviolent offenses that helped make up for the lost money. There was also a 60% increase in the annual likelihood of being incarcerated.

“For men, we see increases in drug distribution and burglary,” Deshpande said. “For women, we see increases in prostitution charges, and fraud or forgery charges, things like identity theft.”

“The first order thing that SSI is doing is preventing crime.”

Manasi Deshpande

Since many crimes don’t result in criminal charges, she said the data is likely an undercount. “For a lot of these charges, you'd want to multiply by five or 10 or even 20 to get the true rate of criminal incidents,” she said.

By Deshpande’s rough estimates, the federal government saves as much money by taking young people off SSI as state and local governments pay out in policing and prison costs for the same people.

“The big takeaway is that SSI has big benefits for young people and for society,” she said. “The first order thing that SSI is doing is preventing crime.”

Bringing SSI into the 21st century

The question nagging public policy experts and SSI administrators is how to reach more kids and enroll them in the program.

A significant challenge is that “children aren’t in their system,” explained David Weaver, a University of South Carolina instructor who previously worked at the Social Security Administration.

Weaver, who spent 24 years at SSA and, at one time, ran the agency's research department for disability programs, said enrollment plummeted for elderly people during the COVID shutdown. But the agency was able to boost participation by sending out letters to social security recipients who were likely to qualify for SSI, alerting them to the additional benefit.

Weaver believes something similar is needed for children. He said the Social Security Administration should partner with other federal agencies, such as the Department of Education, to identify kids who might be eligible and contact them.

Other public policy and public health experts argue for better coordination with schools, children’s hospitals and pediatrician offices to inform more families about the program and help them apply.

In a statement, the Social Security Administration said it’s raising awareness about SSI through ad campaigns targeted at underserved communities and by partnering with local groups.

“We are working with thousands of these community-based groups who have the capacity to assist people in completing applications or provide us with referrals of people who may be eligible for SSI,” the statement said.

“It's time to bring SSI into the 21st century.”

Sen. Ron Wyden

For Sen. Wyden, many of the program's requirements are outdated and overly restrictive. He’d like to update the law that governs SSI. One change he's advocating for would remove a financial penalty families face if a parent works. He'd also like to ease financial restrictions, including a provision that requires applicants to have no more than $2,000 in assets.

“It's time to bring SSI into the 21st century,” Wyden said.

He and Sen. Sherrod Brown, an Ohio Democrat, have drafted a bill to modernize the program. But the price tag — more than $500 billion over a decade — makes some experts skeptical about its prospects.

Connor's mom, Roberta Biscan, said relief can't come soon enough. She now works for a nonprofit organization helping other families navigate government benefit programs.

“I feel like there has to be a change," she said, "a desperate change.”

This segment aired on June 23, 2023.