Advertisement

Why heavy rains shut down many Mass. beaches on hot summer days

Resume

Drenching rain over the July Fourth holiday didn’t just dampen barbecues and delay fireworks. It also caused high bacteria levels that closed 20 saltwater beaches the next day.

State and municipal health officials regularly test the water at all the state’s swimming beaches for bacteria throughout the summer. Almost 95% of the time, the water is safe, according to Department of Public Health data.

But sometimes test results come back too high, prompting immediate beach closures. Last summer, more than 1,000 closures — across 500 saltwater beaches — kept swimmers out of Massachusetts waters. Often, bacteria was to blame, carried to the ocean in runoff from heavy rains that mixed with debris and chemicals on streets and sidewalks. In some cases, sewer outflows cause problems.

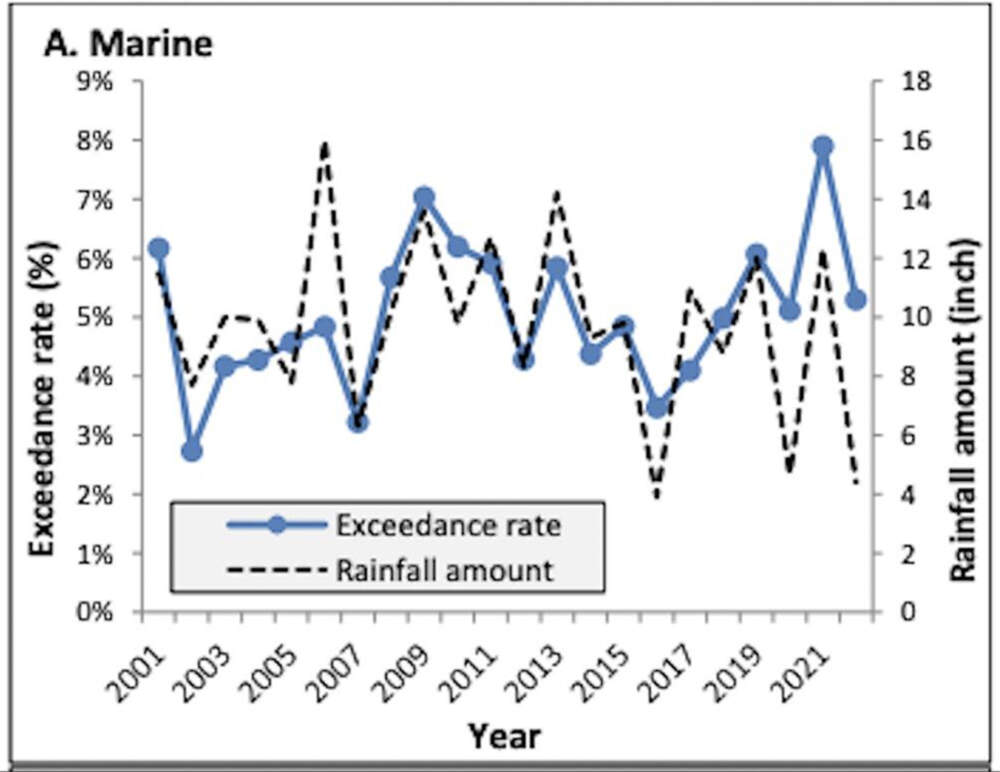

Statewide testing data over the past 12 years reviewed by WBUR show water quality at saltwater beaches fluctuating sharply. On average, about 420 tests come back high each summer — or 5% of all the tests. But in 2021, there was a big spike — to almost 8% — blamed on a very rainy summer.

At Good Harbor Creek in Gloucester, tests in 2021 found high bacteria levels seven times, leading to multiple closures. Then in 2022, the city closed the creek for the entire summer, “out of an abundance of caution,” according to Gloucester's chief administrative officer, Jill Cahill, while consultants tried to determine what was causing the bacterial problems.

That work cost the city $120,000. But there was no clear answer.

“We still don't have any one item to point to that we can say, ‘This is the cause and this is how we'll fix it,’ ” Cahill said.

So far this year, the creek has stayed open. “Our beaches are really our greatest natural resource,” Cahill said. “They're a big part of who the people who live here in Gloucester are, and why people come to visit.” No one wants to have beach closures, she said, with New England’s short beach season.

Mike Puopolo, a Gloucester resident, said he hopes Good Harbor Creek remains open this summer. His young son and daughter love the shallow water that flows into the ocean along its beach.

“They're scared of the big waves and usually this water is a little bit warmer,” he said on a recent visit. “But the last couple years we haven't been able to go in.”

The ups and downs in test results reflect the challenge health officials face in predicting or preparing for seasons when rainy seasons or water problems arise. From the North Shore to Cape Cod, heavy rains and other factors routinely contaminate waters.

The tests capture only a snapshot in time, and water quality can change quickly. Kelly Coughlin, who has worked in water quality monitoring for more than 25 years, wishes there was a more accurate way to let swimmers know if the water’s fine.

“It's always been a pretty flawed system, because your bacteria results are always a day late,” she said. “The technology just isn't there yet to allow accurate, real-time prediction of water quality.”

Last year, Clipper Lane Beach in Dennis saw seven tests with concerning bacteria levels, leading to 19 posted closures. Sandy Beach in Danvers was flagged in six tests. At King's Beach in Lynn, a whopping 62 tests exceeded safety standards.

Lynn’s troubles are worse than most, largely due to storm water discharge. City officials there are seeking funds for a solution: $25 million for a UV light system that kills bacteria.

Other safety reasons can close beaches to swimmers, such as shark sightings. In 2020, several beaches shuttered after jellyfish smacks floated near the shore. That year, marine wildlife shut down dozens of beachfronts for more than five weeks in June and July, according to the Department of Public Health. In total, 21 beaches were affected, including Carson, Constitution, Lovell's Island, Spectacle Island, Nantasket, Nahant, Revere, Scusset and Winthrop.

In fact, in 2020, bacteria was the culprit in only half the closures; too many jellyfish were to blame for nearly all the rest. (Scientists remain unsure about what caused jellyfish numbers to surge.)

Still, while wildlife encounters may be hard to predict, it appears tracing bacterial blooms can also be hard to manage. For one, beaches shut down after bad test results may wind up closed on days when the water has already cleared.

Chris Mancini knows that issue well. He’s executive director of Save the Harbor/Save The Bay, a nonprofit focused on protecting Boston Harbor and state beaches from Nahant to Nantasket. One study of Constitution Beach in East Boston, he said, found that every posted closure was timed wrong.

Because it takes a day to get test results back, "you put the flag up 24 hours later, [when] you actually have clean water,” Mancini said. “You're actually taking beach days away from people.”

Last week, Save the Harbor published its annual report, which showed most of the metropolitan beaches saw better water quality last year than in 2021, helped by a particularly dry 2022.

Even so, King's Beach in Lynn and Tenean Beach in Dorchester struggled. On average, over the last few years, more than 7 of every 10 tests at each location failed, leading to closures. (Both were closed at points this week because of high bacteria levels.)

Coughlin, the water quality manager, said keeping beaches clean — and communicating to the public when they’re not — is complicated.

“That’s the big challenge of a beach manager,” she said. “You’re constantly trying to balance access versus protection.”

This article was originally published on July 06, 2023.

This segment aired on July 6, 2023.