Advertisement

EPA plans to disband board studying wastewater discharge in Mass. Bay

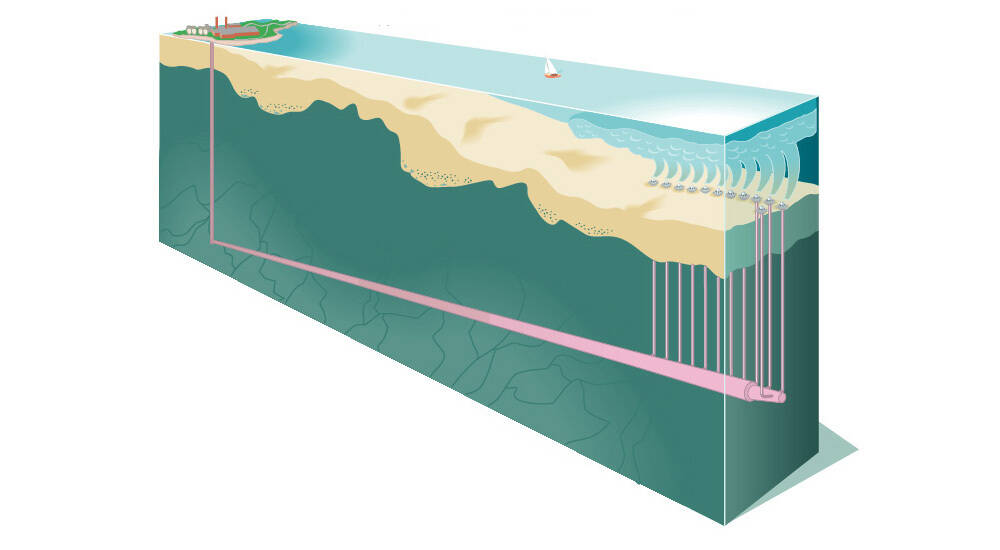

Every day, the Deer Island treatment plant cleans about 330 million gallons of Greater Boston’s wastewater. The treated water is then pumped through a nine-and-a-half mile pipe under the ocean, where it's diffused into Massachusetts Bay.

Since the pipe was built more than two decades ago, the Environmental Protection Agency has required that an independent group of scientists keep a close eye on the treated wastewater and its effect on the bay. This group of volunteer scientists — known as the Outfall Monitoring Science Advisory Panel (OMSAP) — has monitored everything from fish health to algae blooms to oxygen levels in the water.

Many scientists were shocked, therefore, when the EPA announced it plans to discontinue the panel when it renews Deer Island’s discharge permit this year. The EPA declined requests for an interview. But the official reason, according to a statement from EPA New England: While the panel “served a very important role,” the data show that those decades of wastewater discharge have not harmed the bay. So, the scientists’ services are no longer required.

But the scientists say their work has just begun. They see a bay warming with climate change, soupy with microplastics and swimming with unfamiliar algae. Who knows what else the future holds?

“We need to be looking ahead. Climate change is happening and it's happening rapidly,” said Juanita Urban-Rich, an associate professor at UMass Boston and a member of the advisory panel. “Our conclusions from the past 20 years of monitoring may not be relevant over the next coming 10 years.”

“Climate change is happening and it's happening rapidly ... Our conclusions from the past 20 years of monitoring may not be relevant over the next coming 10 years.”

Juanita Urban-Rich

Other supporters say that the advisory panel offers more than just solid science: the group makes data and decision-making transparent, and holds state and federal officials accountable.

“As a person who understands that frank, open discussions and peer review are critical to good science, I am very concerned,” said Bruce Berman, who was the director of strategy and communications for the advocacy group Save the Harbor Save the Bay for 30 years.

The Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA), which operates the Deer Island plant, will still collect data on the health of the bay.

“But the question is: monitoring what?” asked Berman, who also chairs the panel's Public Interest Advisory Committee. Who is going to decide what data they gather, he said, "and how can the public have input?”

Beyond that, it's not clear yet how — or if — scientists and the public will be able to access the data.

Advertisement

“[The MWRA] could just do your monitoring and stick it in a bin and let it sit there,” said Pam DiBona, director of the Massachusetts Bays National Estuary Partnership. “It doesn't make sense not to have scientists pay attention to what the data are.”

The MWRA, for its part, has nothing but praise for the panel of scientists. A statement from the organization stated that it “greatly appreciates OMSAP’s technical and scientific oversight of the Deer Island outfall since it came online.”

Still, the MWRA is not pushing to keep the group in the permit, at least not publicly.

Judith Pederson, an oceanographer at MIT’s Sea Grant and current chair of the panel, put it this way: “While we have a congenial relationship with MWRA, I think they would be happy not to have us.”

Harbor of Shame

Back in the 1980s, Boston Harbor was a national embarrassment. It was widely derided as the dirtiest harbor in America and blasted in headlines as the “Harbor of Shame.”

“There was so much pollution in Boston Harbor that it was constantly at risk of ginormous algae blooms that used up all the oxygen," Berman said. "Anything that couldn't swim the hell out of the harbor would die.”

“The water was green. And brown on some days," he said. "We were discharging 250 million gallons of crap out of a broken pipe, out of an old plant right off the mouth of the harbor. You could see that plume from space.”

Lawsuits eventually forced the cleanup of Boston Harbor. In 1985 the state legislature created the MWRA to take over the water and sewer system for Greater Boston. One key part of the cleanup plan was a $3.8 billion upgrade for the Deer Island wastewater treatment plant, and a new 9.5-mile pipe that would discharge treated wastewater, or “effluent,” into the bay.

Not everyone loved the idea of dumping Boston’s wastewater — treated or not — into the bay. Coastal communities on Cape Cod and the North Shore were concerned that Boston’s sewage was about to become their problem, washing up on their shores.

“There were people who thought that we were gonna save the harbor and screw the bay,” said Berman.

To address these concerns, the state created an Outfall Monitoring Task Force, which collected data for almost a decade before the outfall pipe went into service. Then, when the outfall pipe began discharging into the bay in 2000, the EPA required the scientific oversight panel in Deer Island’s original wastewater permit, along with stringent effluent limits and monitoring requirements.

As outlined in the group's charter, EPA and MassDEP jointly chose scientists and engineers to serve on the panel, selecting people with expertise in Boston Harbor, Massachusetts Bay, Cape Cod Bay and the Gulf of Maine. Current members hail from places like MIT, Northeastern and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

The scientists aren't being cut from the permit for cost concerns; they all volunteer their time. The MWRA estimates that the outfall monitoring costs about $1.5 million each year, but most of that money goes toward the actual data collection. When the scientists get together, the EPA usually provides the meeting space.

While the panel has no formal mechanism to compel state or federal agencies to act, the scientists have wielded considerable power. Over the past two decades, the scientists have devised plans to monitor nitrogen and dissolved oxygen in the water. They’ve studied piles of data from monitoring stations; evaluated the health of flounder and lobster; and convened special studies, like those on microplastics, PFAS and other so-called contaminants of emerging concern. And while state and federal authorities may not have loved all the scientist’ suggestions about what to monitor and when, said Pederson, she can't recall any suggestions that weren't adopted in the end.

“There were people who thought that we were gonna save the harbor and screw the bay.”

Bruce Berman

“They were charged with coming together and keeping an eye on the data," DiBona said. "They've done an amazing job."

Their biggest finding was that those millions of gallons of cleaned-up wastewater flowing into the bay didn’t have much effect.

This is why the EPA argued that the panel is no longer necessary.

“Nearly 23 years of ambient post-discharge monitoring has found that Massachusetts Bay water quality standards for the waters around the discharge are being met, and the discharge has not had an adverse effect on Massachusetts Bay,” said Michelle Barden of EPA New England in a July 12 public hearing. “EPA is dropping the outfall monitoring Science Advisory panel, or OMSAP, as a permit requirement.”

Many argue that the past effects of the discharge may not be indicative future impacts, given the rapidly changing climate.

Virginia Edgcomb, a senior scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and a member of the panel, pointed out that new species of harmful algae are being detected more frequently in Massachusetts Bay and Cape Cod Bay, usually triggered by warm water and available nutrients. These algae are the suspected culprits in the low-oxygen “blobs” that have killed lobsters in Cape Cod Bay.

As the water warms with climate change, she said, these patterns “need to be monitored carefully.”

Judith Pederson, the current chair of the panel, said she worries about “contaminants of emerging concern,” like PFAS and microplastics.

“I don't feel that this permit has looked forward at all,” she said.

Maybe there’s another way forward

While Deer Island is the largest source of wastewater discharge into Massachusetts Bay, it isn’t the only one. Pederson and others think that the panel should broaden its reach and monitor all the facilities discharging wastewater into Massachusetts Bay.

“Isn't it stupid of us to have all of Mass. Bay and only have one monitoring program out there?” she asked.

Even as EPA New England plans to remove the science advisory panel from its permit, the agency seems to support an ongoing role for the group — just, maybe, somewhere else. In a statement, the agency said it's been working with panel members "to encourage the establishment of a regionally focused Massachusetts Bay Science Advisory Board.”

One of the most likely homes for a future panel is the Massachusetts Bays National Estuary Partnership (MassBays), now housed at UMass Boston’s Center for the Environment.

The Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection "has been in discussions with MassBays as a potential host organization," said spokesman Ed Coletta, adding the department is considering various options for continuing the panel.

“MassDEP recognizes the value in a third-party science advisory committee," he said.

However, there seems to be little action beyond discussion. And, there’s another concern with the group landing at UMass: it’s unclear whether they could wield any real power without formal state or federal backing.

“We would have to be careful that they actually have some weight,” DiBona said. “They all volunteer their time to look at these monstrous piles of data. And they're not going to do it if they don't think it's going into something that's worthwhile.”

“I don't mind that they don't have us in the permit as long as they have us somewhere where we report either to the state or to EPA,” Pederson said. “That really is what you need. If you don't have that, they won't care.”

There has been little public outcry about the looming dissolution of the group. The public comment period on the proposed permit opened on May 31 and ends on Nov. 28. So far, there are no comments on the elimination of the panel. A public listening session on the group’s future in July garnered lots of input from panel members, former members and allies, but none from the general public.

Scientists “are really good at asking and answering very complicated questions. They are not really good at self-promotion,” Berman said. “Sometimes it’s hard to get people to pay attention.”

Judith Pedersen said that for scientists, the work on the bay is just getting started, and climate change has added a sense of urgency.

“Things are changing quickly,” she said. Their decades of monitoring are just a short window into the history of the bay, but may prove crucial with the rapid climate shifts underway. “You really need to keep going.”

Correction: The radio version of this story mistakenly referred to Jeffrey Rosen, an environmental scientist and member of the Outfall Monitoring Science Advisory Panel, by the wrong first name. We regret the error.

This segment aired on August 21, 2023.