Advertisement

From examining the dead to guiding the living, Tom Andrew embraces his 'third act'

This story is part of WBUR's "The Third Act" series, highlighting people who worked full careers and re-invented themselves later in life, often in surprising and inspirational ways.

As the sun set on the placid waters of Lake Eileen in central New Hampshire in July, a bugle sounded, and Scouts gathered to lower the flags before dinner. The boys and girls had spent the day swimming, sailing, kayaking and learning first aid, handy crafts and horseback riding at the Hidden Valley Scout Camp. Now, tacos were on the menu.

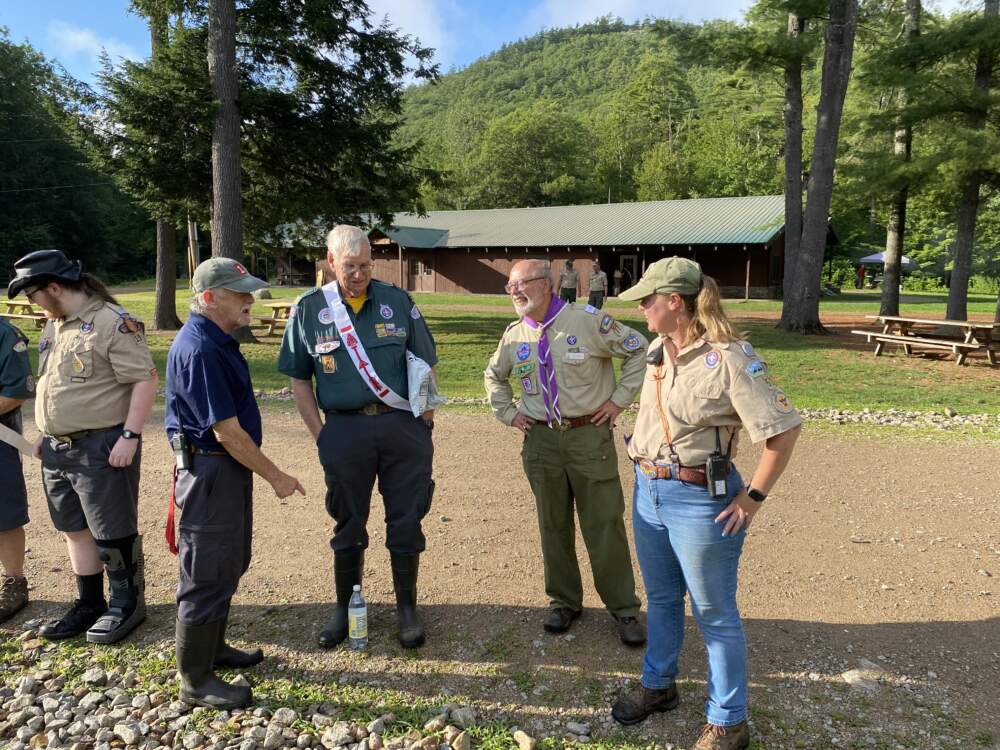

Among the Scout masters and staff lining up for dinner was Tom Andrew, the chaplain. Decked out in a uniform of green trousers, khaki shirt and a purple neckerchief, he bantered easily with some of the kids about this year's National Scouting Jamboree in West Virginia.

"It was fantastic — in fact, it was super fantastic," declared Andrew. He asked one of the Scouts if he planned to attend next year's jamboree.

"I'd like to," the boy replied. "It sounds amazing."

Married, with three grown children, Andrew is making a major transition at the age of 67 — from forensic pathologist to Methodist deacon. Deacons are ordained clergy who serve beyond the walls of an individual church and find their own ministries. Andrew said working with the Scouts was a natural fit for him, given his own experience as a Boy Scout.

"I want to be part of giving a marvelous scouting experience to the kids who are in the program today," he said in an interview.

The roots of his religious faith were planted long ago. Andrew grew up in Dayton, Ohio, where, he said, he preached his first sermon as a Scout at 14.

"I think I spoke about a Scout's duty to God, and I remember concluding by saying something like, 'Thanks for listening to a goofy teenager.' "

Now, as a chaplain, he says his focus is less on preaching and more about being a "non-judgmental listening presence" for young Scouts.

"If you can point them in a certain direction and help them find their own way, all the better," he said. "But it's by and large a ministry of presence and listening."

Andrew's new avocation is also about helping the living, after a career as a forensic pathologist, studying the dead. Trained in pediatrics, he went on to spend 20 years as the chief medical examiner for the state of New Hampshire. There, he witnessed up-close the grim toll of car accidents, gunshot wounds, poisonings, assaults and suicides. He said it was a job that gave him a particular appreciation for the fragility of life.

Advertisement

"A medical examiner sees a skewed view of everything, because it has ended fatally," Andrew said.

He said his wife, Rebecca, has been supportive of his career change, despite some initial reservations about finances. (They still had two kids in college when he retired from the state.) But given their involvement in their churches over the years, he said, "My call did not come as a surprise to her."

She also understood well the stresses of his work as a medical examiner. Toward the end of Andrew’s tenure, the deadly opioid crisis was overwhelming the state and his office. Heroin and prescription opiates like Oxycodone were killing people at alarming rates. Andrew said he tried to sound the alarm, predicting that drug deaths would soon surpass traffic fatalities in the state.

"That got people upset," said Andrew, recalling that federal health officials accused him of being alarmist and of exaggerating the gravity of the opioid addiction crisis. But his prediction proved prescient, and by 2016 annual drug deaths approached 500 in the state, a 10-fold increase from 2,000, and continued to climb, dwarfing traffic fatalities.

Andrew became increasingly frustrated with what he saw as a slow response to the growing crisis in the "Live Free or Die" state.

"I could not reconcile that with what I was seeing and what I was feeling," Andrew said.

By 2017, Andrew decided he'd had enough and retired. He was 64. Katharine Seelye of The New York Times reported the story, headlined, "As Overdose Deaths Pile Up, a Medical Examiner Quits the Morgue," a powerful feature about the runaway addiction crisis and the despair of one man tasked with tallying its victims.

What Andrew did next is the focus here: he began a new phase in his life — his "third act." He enrolled in seminary school and obtained a master's degree in divinity. He's now undergoing the slow process of Methodist ordination, sitting for a series of annual interviews with church elders. He's currently a provisional deacon, and if all goes according to plan, he will become an ordained deacon in 2025, just shy of his 69th birthday.

"What does late in life mean anymore?" he asked. "Sixty is the new 50."

"What does late in life mean anymore? Sixty is the new 50."

Tom Andrew

Andrew said he could easily have retired to a cabin in the woods with his books, but figured, "I'd probably be dead in five years." Instead, he felt he had the health, energy and passion to pursue this new chapter.

His decision to reinvent himself is part of a larger trend. In general, people are living decades longer than they did at the beginning of the 20th century. And either by choice or necessity, they're now working longer.

"A little over a century ago, life expectancy in the U.S. was about 47 years," said Barbara Waxman, a California-based gerontologist and life coach who writes and lectures about this phase of life. "Today, it hovers around 80."

We've added 30 years, she said. That's true even with life expectancy ticking down slightly over the last few years, due to the pandemic, drug overdoses and suicides, among other reasons.

The traditional idea of three stages of life — learning, earning and retiring — is increasingly seen as outdated. Instead, many people like Andrew are discovering that life can reset at age 50, 60, 70, or even later.

Every day, 10,000 baby boomers reach retirement age but lots of them aren't ready to stop working, either because they can't afford to, or, like Andrew, they don't want to.

Waxman said for most people, living longer doesn’t mean experiencing old age for a longer stretch. Instead, their midlives extend into a period Waxman calls “middlesence.” Like adolescence, middlesence can be a time of change and tumult, but also of opportunity and growth — if people can give up the “sticky commitment to conformity,” Waxman said.

"It’s actually a gift if we can shift our cultural narrative about this expanded midlife," she said.

Andrew continues to do consulting work as a medical pathologist, but said his passion now lies with ministering to the Scouts. He said all the effort to become a Methodist deacon will be worth it if he can help kids — maybe even save one of them from making bad choices about drugs.

"I spent 20 years on the assessment end, counting the cost," he said. When he decided to leave the medical examiner's office, he was eager to work with young people to help them see "there's a better way than that pill or that powder."

The Rev. Dr. David Abbott, director of stewardship at the United Methodist Foundation of New England, served as Andrew's mentor when he began his ordination journey. He said Andrew, at his age and with his long experience as a doctor, brings wisdom to the new role, along with an admirable dose of humility.

"Tom went from being the expert who shared to being the student who learned," Abbott said. "He's not full of himself, he's just full of love," he said, noting that sometimes it felt as though Andrew was the mentor and he was the student.

"It’s actually a gift if we can shift our cultural narrative about this expanded midlife."

Barbara Waxman

For her 2009 book, "The Third Chapter: Passion, Risk and Adventure in the 25 years after 50," Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot interviewed dozens of people like Andrew, who chose new careers or adopted new skills later in life. They included an industrial chemist who became a sculptor in his late 60s; a former journalist and newspaper executive turned jazz pianist; a 60-year-old physicist who went on to teach science to low-income teens.

"I believe that this time between 50 and 75 may be the most generative and transformational time in our lives," Lawrence-Lightfoot said.

A professor of education at Harvard University, Lawrence-Lightfoot said third acts can be liberating. But they can also be difficult at the outset, because they require a leap into the unknown. For older people, the task can be particularly daunting, she said, as they face learning new skills, maybe even giving up status as they transition from experienced elder to an older beginner.

"This is really very challenging," she said. "Part of this process of growing and taking risks is being willing to be vulnerable."

Back at Scout camp in New Hampshire, Andrew said grace before the weekly scoutmaster dinner, offering what sounded like a reflection on the aim of his own third act.

"Let us remember that we are here for the young people we serve, to offer them the best week of camp we can," he said.

Not surprisingly, Andrew's career transition has its occasional difficult moments. He said he sometimes loses confidence in his ability to remake his life or gets frustrated with church bureaucracy. But the opportunity to help young people draws him back to camp each year. At the World Scouting Jamboree last year, he had one of those chances.

A young Scout from Britain was having a difficult time, Andrew said. "He had come to the conclusion that he did not believe in God, and he was facing the prospect of going back home and having to tell his mother this," Andrew recounted.

"I wasn't there to say, 'No, you're wrong — you have to believe in God,' " he said. "Basically, you're here to hear them out."

So, Andrew listened. He learned the young man had an uncle, a man of faith, with whom he was close. Andrew urged the boy to ask his uncle to help navigate the difficult conversation with his mother. And that advice appeared to help.

"It was a little thing," he said. "But bringing some measure of comfort to him, seeing the tears dry up, seeing the smile on his face, was absolutely worth the whole time I spent at the Jamboree."

Andrew said his third act, what some might call his "middlescent reboot," has been a risk worth taking.

"If you're passionate, if you're energized, then I think you use that passion and energy in a way that not only extends your own life, but you might be able to share something with someone else," he said. "And that's exciting."

Have you re-invented your life in a surprising or inspiring way? If so, we want to hear about it. Email us at thirdactstory@gmail.com.

This segment aired on October 23, 2023.