Advertisement

70 years later, survivor recalls Boston ship blast that killed 37

This month marks 70 years since a horrific event on the Boston waterfront.

The explosion aboard the USS Leyte happened on Oct. 16, 1953 at the Boston Naval Shipyard in South Boston, which no longer exists. It killed 37 people, including five civilians. It was the largest loss of life ever on the Boston waterfront, according to the U.S. Naval Institute.

And it's largely forgotten.

The USS Leyte was an aircraft carrier that won two battle stars for its distinguished service in the Korean War. The 27,000-ton vessel could hold 1,400 sailors and 100 aircraft.

Three months after the truce in Korea, the Leyte was in Boston for modernizing. Workers were converting it from an aircraft carrier to an antisubmarine carrier, better to fend off Soviet subs.

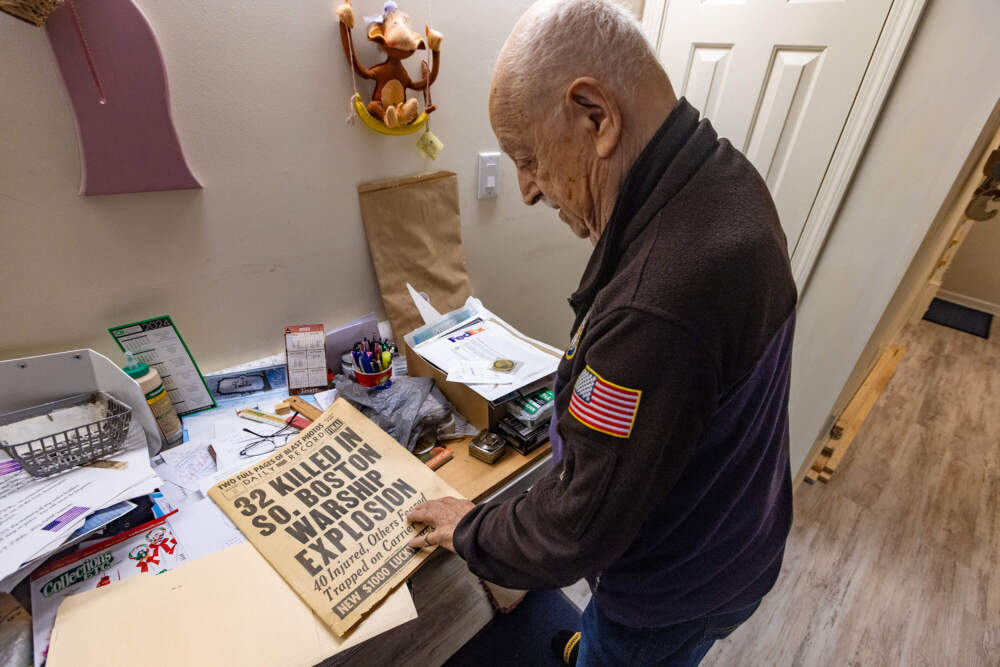

Jim Tsihlis, 92, of Arlington still remembers those days well. In 1953, he was a petty officer third class, and he had been assigned to the USS Leyte just one week before the explosion happened.

The mid-afternoon blast was thunderous. All the clocks on board stopped.

"I was on the dock, taking supplies from the dock, bringing [them] aboard the ship," Tsihlis said. "And there was a commotion aboard the ship, when everybody said, 'Fire! Fire!' And when that happened, I dropped everything, and I helped the sailors with water hoses. So I did the best to help, as much as I could."

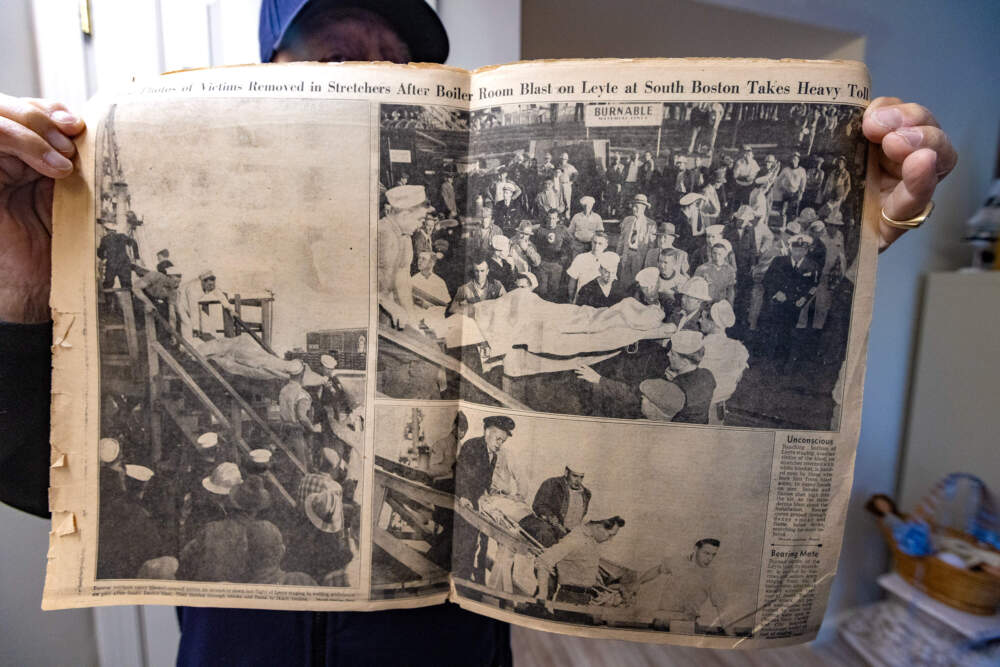

Billows of black smoke spewed from the ship and filled the air across the navy yard.

"Flames mushroomed through the forward part of the ship, [and] belched into the air about 25 feet above the hangar deck," said David Hannigan, a park guide with the Boston National Historical Park. That's a collection of National Park Service sites including the Charlestown Navy Yard, where a plaque memorializing the USS Leyte disaster stands. "An oil line was ruptured [and] that began to fuel the fire. You just would see burning and scorching. Men were hurled across the flight deck."

Witnesses said the blast started four levels below the flight deck in a catapult room. The catapult is the sling-shot-like technology that helps propel planes during takeoff from the short runway of a ship. Some people suspected sabotage. But the Navy said a valve leaked flammable hydraulic fluid, and the spark ignited the fire. It might have happened when someone flipped on a light switch.

Advertisement

According to newspaper reports from the time, firefighters said temperatures on board the vessel hit 200 degrees. They felt the heat from the steel decks through their boots. Rescuers poured water into the smoldering hatches as Navy men on board pulled everyone out of the brig. Some braved the black smoke and found the bodies of trapped sailors lying in water and oil. They dragged them up escape hatches to safety.

"After the fire, they called everybody aboard to get onto the hangar deck so they could count who was alive and who was not alive. And after they did that, they furnished us with coins to call our families," Tsihlis recalled.

He said it saddens him that the tragedy is not remembered and recognized.

"It's strange. It really is. And you don't hear anything. I have spoken to people my age, and they've never heard of it," Tsihlis said.

Selby Herald, a civilian machinist, was killed in the blast. His son, who was named after him, turned 9 years old the day of the explosion.

"I remember that before [my father] went to work, he said, 'I'll see you when I get home,' " said the younger Herald, who lives in Falmouth.

The family had been planning to celebrate his birthday with cake that evening. Instead, two Navy officials came to the house to tell the family there'd been an accident.

When the anniversary of the blast comes around, Herald's brother mentions it. But Herald said he himself doesn't dwell on it.

Losing his father as a young child left his mother to support the family, he said, and that taught him how to fend for himself.

"I guess you become stronger, and we grew up pretty much on our own," he said. "My mother [would tell us], you know, 'Just stay out of trouble,' which we did. So I'm doing OK in life."

The site of the former Boston Naval Shipyard is now called the Raymond L. Flynn Marine Park. David Hannigan, of the National Park Service, is likely one of the few Bostonians who, when near the site, reflect on the catastrophe.

"You can't help but think about an event like this, because prior to the Leyte disaster, they had gone 19 years without a single fatality at the Navy yard — which is remarkable, especially considering that during the Second World War, the peak labor force was in excess of 51,000 men and women," Hannigan said. "And in all the years that America was fighting the war, there wasn't a single life lost at Boston Naval Shipyard."

The USS Leyte returned to sea three months after the tragedy. She was decommissioned in 1959 and sold for scrap in 1970.

This segment aired on October 23, 2023.