Advertisement

Field Guide to Boston

Louisa May Alcott used pen names. A researcher thinks he found another

Resume

A researcher believes he has a batch of 14 previously unattributed works written by the author of “Little Women” — under a pseudonym. Louisa May Alcott was known to publish under various names throughout her writing career, but this discovery marks the first time any new pseudonym has been linked to Alcott since the 1940s.

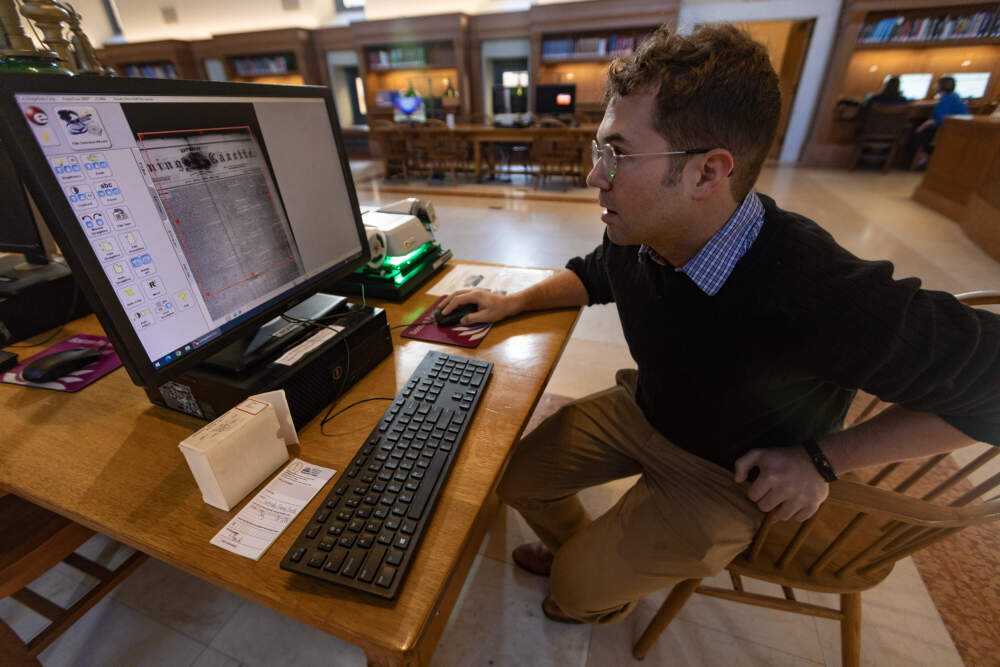

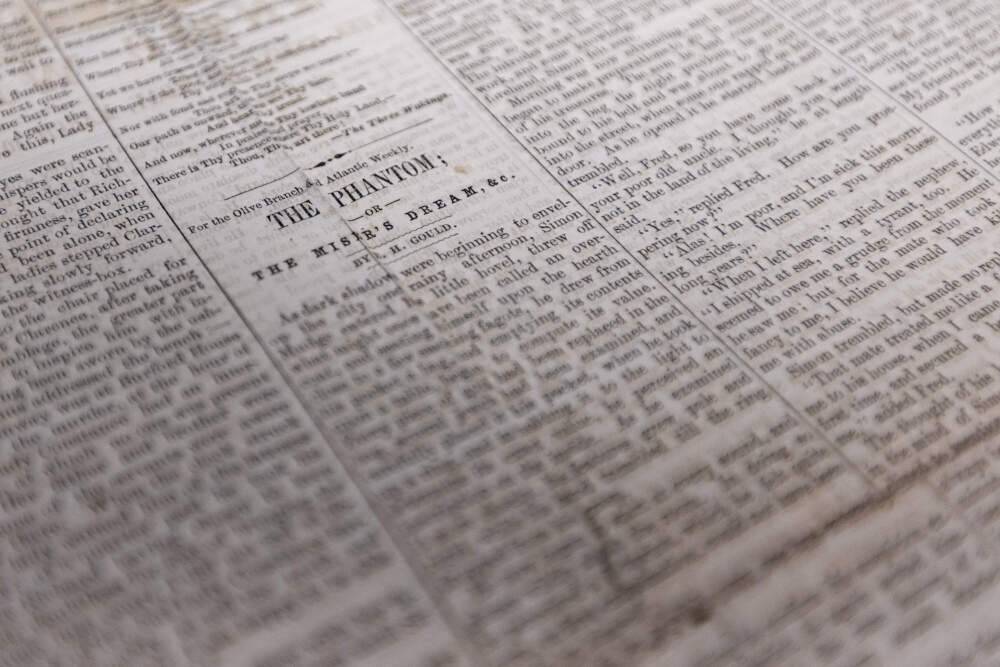

Dr. Max Chapnick sifted through libraries and digital archives for weeks at a time. He was searching for undiscovered works by Alcott, and he had little luck, until one day, when he found a promising short story published in an 1860 newspaper. The writing had signature traits of Alcott’s work, but there was one significant issue: the byline underneath a short story, called “The Phantom,” credited an author named E. H. Gould.

Chapnick dismissed the story as yet another unfruitful leg of his search. He went to bed, fell asleep and woke with a feeling of eureka. “At like 1 a.m. I woke up and I was like, ‘Oh, wait, what if it is? What if the story is by her and it's a pseudonym?’” Chapnick recalled.

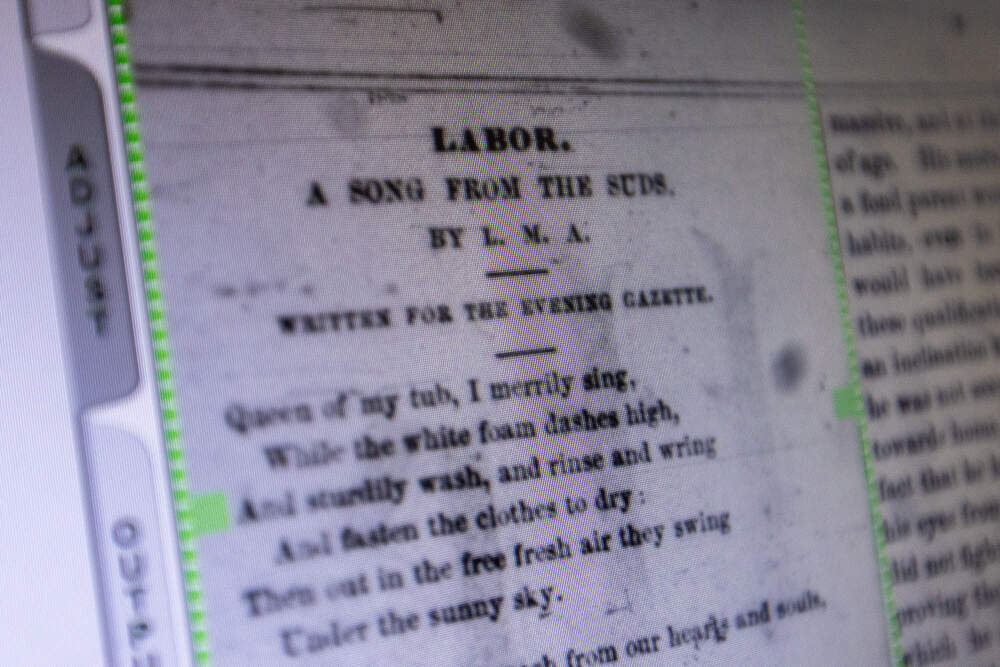

Alcott used aliases throughout her career for varying reasons. A. M. Barnard, Flora Fairfield, Tribulation Periwinkle and simply L. M. A. are among the most notable. Like her anonymously published works, pseudonyms with first initials such as A. M. Barnard gave Alcott an opportunity to take her pen to more controversial subjects and styles. Some of these names were known during Alcott’s life and many more in 1950 when Madeline Stern published findings from her research throughout the 1940s. Her work set off a chain reaction of new attributions for decades and built to a crescendo of feminist commentary in the 1980s and 90s.

Stern’s 1950 biography of Alcott was the most recent time a researcher tied a new pseudonym to Alcott – until Chapnick’s discovery. The fact that E. H. Gould is not only new but also masculine sounding and from her early days as a writer means that this discovery will likely provide a new insight into what a young Alcott wanted to say on topics of gender, sex and power.

“The Phantom” uses the format of one of Alcott’s favorite writers, Charles Dickens, to explore such themes. “It's like a spoof on the Christmas Carol story,” Chapnick said. “The Scrooge character's coins are talking, which is kind of silly and fun. And it's not just an allegory or a moral tale about why we shouldn't be greedy, but there's an element of sexual quid pro quo, where the Scrooge character is trying to bribe or manipulate this young woman into marrying him. And so he sort of learns that you not only shouldn't be greedy, but you shouldn't exploit women by trying to make them your wife.”

Alcott noted a work titled “The Phantom” in her personal journals, and scholars have long regarded the title as a missing work. This discovery set Chapnick on a course for further evidence to determine whether Alcott was truly the author. He searched for either E. or I. H. Gould as the digital scan of “The Phantom” had a fold that partially covered the first initial.

Ultimately Chapnick unearthed seven short stories, five poems and one work of nonfiction credited to E. H. Gould and published his findings in J19. He also found another work by Alcott under her own name that scholars had previously missed. “If in the course of searching for Gould, I actually found yet another story that's under Alcott's own name that we haven't yet found, there's got to be more,” said Chapnick, who is now a postdoctoral teaching associate at Northeastern University. “Maybe there's some farmhouse in New Hampshire,” he continued, speaking on the nearly endless possibilities of where printings of Alcott’s lesser known works could be discovered.

“I don’t think anyone, until Max, has discovered a new pseudonym that can be so confidently traced back to Alcott’s authorial hand,” Dr. Gregory Eiselein, president of the Louisa May Alcott Society, wrote in an email. “This is a major, even stunning contribution to research on Alcott’s early career.”

Dr. LuElla D’Amico, an English professor who has published research on the literature and girlhood of the 19th century, also wrote via email, “What Max has potentially discovered with the E. or I.H. Gould pseudonym suggests that Alcott specifically dabbled with supernatural elements in her writing prior, and more prominently, than she had been considered to do so in the past—in the 1850s rather than the 1860s.”

One of the reasons Chapnick found “The Phantom” in the first place was the digitization efforts of archivists at the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, which has one of the largest collections of North American texts printed before the twentieth century.

Elizabeth Pope, curator of books and digitized collections spoke on the state of archival digitization efforts. “People sometimes think that everything is on Google, [and] everything's been digitized and is in Google Books,” Pope said. “It’s really uneven.” The American Antiquarian Society has worked for 70 years to make works from their physical archive accessible far and wide, first with microfiche, then microfilm and now digital scans. While better funded institutions such as The American Antiquarian Society and the New York Public Library have made strides, there’s still work to be done to digitize their large collections. Smaller and lesser funded archives are even less digitized, if at all.

Pope helped further the research when she unfolded the original printing from the March 10, 1860 edition of weekly weekend newspaper The Olive Branch to confirm that “The Phantom” too was credited to E., not I., H. Gould. She emphasized how digitization and preservation of original documentation work hand in hand in research. “We might be able to find new light shed on those figures that we are already aware of, because we can now keyword search in the digital version of whatever it may be, a periodical or a newspaper.”

The current state of digitization means that researchers may rediscover works under both Alcott and Gould for decades to come. The works Chapnick found are not only significant because of what lies within them. The fact that there’s a new pseudonym inspires Alcott scholars who now see new avenues in research.

Jan Turnquist has been the executive director of The Orchard House for over two decades. She was also a close friend of Stern, who was the most recent person to correctly propose a new Alcott Pseudonym. Stern and her partner Leona Rostenberg discovered the A. M. Barnard pseudonym by locating a letter between an editor and Alcott that referenced the name. Turnquist’s eyes lit up as she spoke on how researchers may further verify Chapnick’s theory. “Because that would now give us the opportunity to look at Houghton and other places where there might be letters from publishers of little papers like The Olive Branch, to have perhaps written to Louisa Alcott to say, ‘If there are any other stories you want this Mr. Gould to publish, I would be happy to do it.’”

As for Chapnick, he hopes his work inspires others to find further evidence to either bolster or even discredit his theory of attributing Gould to Alcott. “If you're a scholar or even a casual reader, there's a long history of casual Alcott detectives,” he said. “There's more out there. Even if the Gould stories are not Alcott, there's more out there.”

Read both “The Phantom; Or, the Miser’s Dream” by E. H. Gould and “The Painter’s Dream” by Louisa M. Alcott published in their entirety, courtesy of J19.

Correction: A previous version of this article referred to Max Chapnick as a graduate student. He is presently a postdoctoral teaching associate at Northeastern University.

This segment aired on October 31, 2023.