Advertisement

Review

For its 30th anniversary, 'Farewell My Concubine' returns to the big screen

Unavailable for years except via bootlegs and old, out-of-print Miramax DVDs, director Chen Kaige’s magisterial 1993 melodrama “Farewell My Concubine” is finally back on the big screen, celebrating its 30th anniversary at the Brattle Theatre in a spectacular new uncut 4K digital restoration. Even if you’ve seen the movie, you’ve never seen it like this. The good folks at Film Movement Classics have restored Chen’s masterpiece to its original 171-minute running time, which had been truncated for U.S. audiences by distributor Harvey Weinstein. (Within the industry, he was known as “Harvey Scissorhands,” as there were few movies under Weinstein’s aegis that the convicted rapist didn’t endeavor to “improve” by smearing his greasy fingerprints all over them. Directors like Martin Scorsese, Guillermo del Toro and Bong Joon Ho have all told horror stories about Harvey’s idiotic input.)

“Farewell My Concubine” shared the Palme d’Or with Jane Campion’s “The Piano” at that year’s Cannes Film Festival, and still remains the only Chinese-language movie to win the festival’s top prize. But according to Peter Biskind’s 2004 book “Down and Dirty Pictures: Miramax, Sundance and the Rise of Independent Film,” jury president Louis Malle warned American audiences, "The film we admired so much in Cannes is not the film seen in this country, which is 20 minutes shorter — but seems longer because it doesn't make any sense. It was better before those guys made cuts."

That “Farewell My Concubine” proved to be an arthouse blockbuster even in its compromised form is a testament to the power of the performances and Chen’s staggering Technicolor vistas, which looked unlike anything else in movie theaters at the time. (And especially unlike anything you’ll see today.) The film is a grand, old-fashioned epic with a cast of thousands, covering 50 years of Chinese history through the eyes of two orphans abandoned to the brutal tutelage of the Peking Opera.

The story starts in 1924, beginning in black-and-white with color bleeding into the scenes as we get rolling. Rough-and-tumble young Duan Xiaolou — so hard-headed he can break bricks over his skull — acts as friend and protector to new arrival Cheng Dieyi, an androgynous wisp of a thing dropped off by his mother when he got too big to keep at the brothel. Together, the boys endure a Dickensian nightmare of physical conditioning and abuse to become premier practitioners of an ancient and rarefied art. In the words of their sadistic Master Guan, “If you belong to the human race, you go to the opera. If you don't go to the opera, you're not a human being.”

The boys find fame and fortune with their rendition of an old chestnut called (you guessed it) “Farewell My Concubine,” in which Xiaolou portrays a faltering warlord king on the verge of being vanquished. Dieyi co-stars as the faithful consort so loyal she uses his sword to cut her own throat rather than bear witness to his ruin. The sexual politics of the piece are suspect, to say the least. Especially when creepy old benefactors use their wealth and opera expertise to score some private time with Dieyi, whose gender-bending performance they find alluring in ways that Chinese censors would rather have not seen depicted onscreen. (The movie was initially pulled from release and banned by the politburo, who eventually relented after removing 14 minutes from the film, allowing it to be shown only because they feared the bad publicity of suppressing a Palme d’Or winner would harm their petition to hold the 2000 Olympics in Beijing. Sydney got the Olympics. But we still got the movie.)

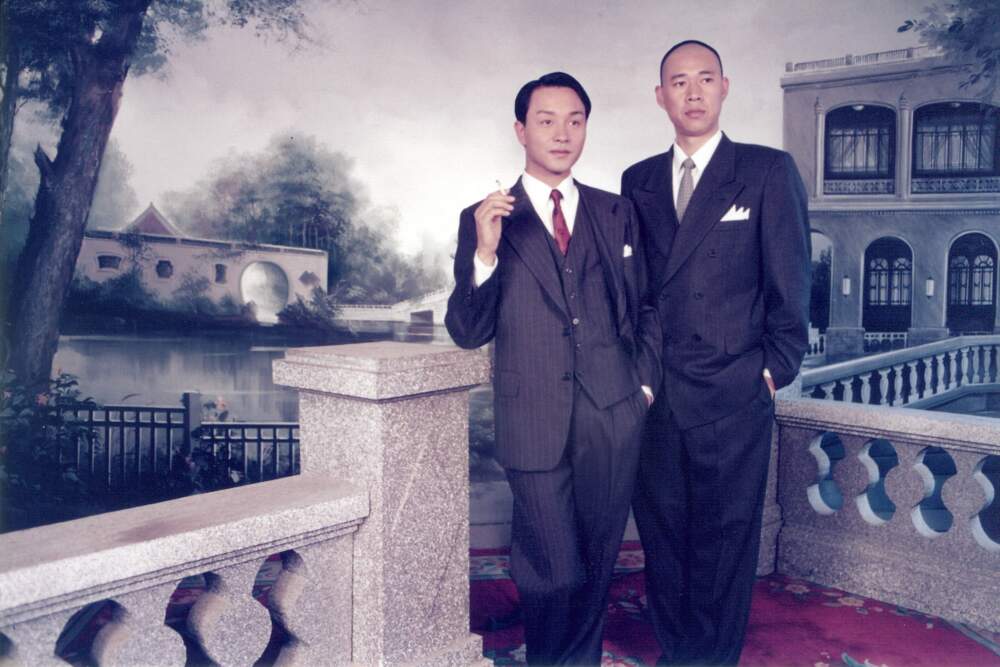

Xiaolou and Dieyi are played as adults by Fengyi Zhang and Cantopop superstar Leslie Cheung, with the majority of the story chronicling the ups and downs of their careers through the tumultuous second half of the 20th century. We catch up with our boys in the 1940s, the “stage brothers” sticking together through the Japanese occupation but nearly torn asunder by something even more dangerous than war: a woman. The ravishingly beautiful Gong Li co-stars as Juxian, a courtesan at the House of Blossoms where Xiaolou likes to unwind between performances. While gallantly protecting her from some overenthusiastic patrons, he jokingly proposes marriage and somehow it seems to stick. Our dynamic duo is suddenly a threesome, an arrangement that doesn’t suit Dieyi at all.

Advertisement

Though already widely admired for his work in Hong Kong classics like John Woo’s “A Better Tomorrow” and Wong Kar Wai’s “Days of Being Wild,” it was his anguished performance as Deiyi that made Leslie Cheung a legend. The precision and feminine grace he brings to the opera scenes are striking, but he’s even more overpowering offstage, aching for his childhood friend with a love that dare not speak its name. For all the pomp and period detail, “Farewell My Concubine” is, at heart, a swooningly soapy love triangle, owing more to “Dr. Zhivago” than to Chinese history books. Deiyi and Juxian find themselves fighting for the heart of a man who loves them both, albeit in ways that can fully satisfy neither. The specter of suicide looms large in the picture, not just enacted onstage every night but also in the horrors of the Cultural Revolution, whose practitioners have little time for these relics and their decadent art.

The movie was an act of atonement for its director, who had joined the Red Guards in his teenage years and formally denounced his father — himself a maker of films about the Peking Opera. (After they patched things up, Chen Huai'ai wound up working for his son as art director on this picture.) Following his tenure working at a re-education camp in Hunan, Chen Kaige outgrew his political fanaticism and even spent a year at New York University’s film school on a Rockefeller scholarship, presumably becoming the only member of Mao’s Army ever to direct a Duran Duran video. He and Zhang Yimou were at the forefront of China’s Fifth Generation film movement, renowned for a series of lavish historical epics (mostly starring Gong Li) of which “Farewell My Concubine” was the crown jewel.

Cheung took his own life in 2003. With this re-release following the recent restoration of “Days of Being Wild,” it’s wonderful to have his most iconic performances back in circulation, so a whole new generation can experience his talent. Seeing “Farewell My Concubine” returned to its full glory is like seeing the film for the first time. Here’s hoping its success begins a trend of repairing all the other independent and foreign language films that were mutilated by Weinstein during his lamentable reign over arthouses.

“Farewell My Concubine” is playing at the Brattle Theatre through Wednesday, Nov. 8.