Advertisement

Museum of Fine Arts unveils a new gallery devoted to Judaica

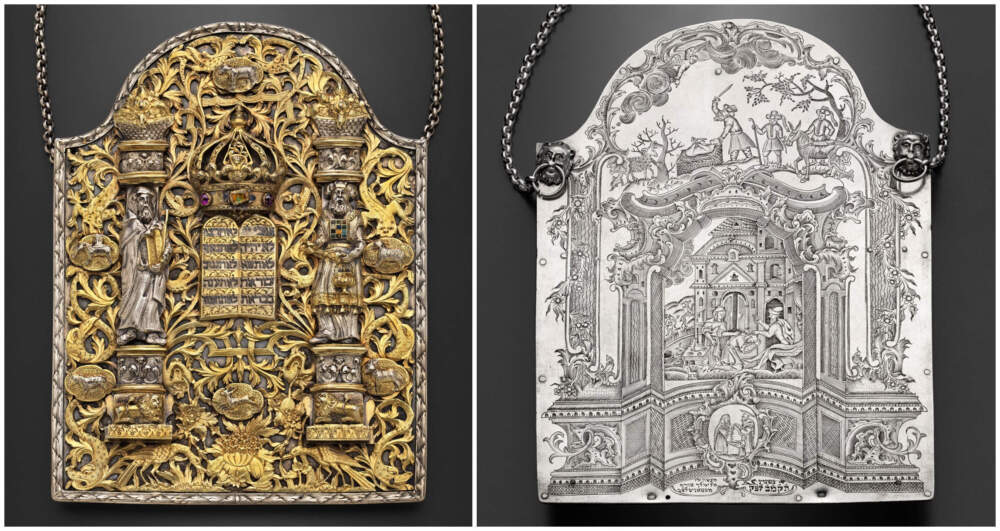

At the end of the 18th century, Elimelekh Tzoref, a master Jewish goldsmith from Galicia (now Ukraine), created a dazzling, intricately detailed Torah shield, an ornament hung around a Torah scroll.

Made of partially gilded silver, enamel and stones and only eight inches high, the Torah shield was lavishly decorated with biblical imagery on both sides.

At the bottom of the back, the artist engraved his signature in Hebrew and the year 5542 (1781/82 on the Gregorian calendar.)

More than a century later, across the continent in Boston, Samuel Katz, a Jewish immigrant from an area now in Ukraine, crafted a Torah ark, the cabinet that holds the Torah scrolls.

A highly skilled and much sought-after wood carver, Katz’s 11-foot ark was adorned with religious symbols including a gilded pair of lions, the Ten Commandments and a crown. It was carved sometime between 1920 and 1930 for Shaare Zion Synagogue in Chelsea, the city north of Boston that was home to immigrants and teeming with Jewish life.

Now, the two sacred ritual objects will share a space at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston’s new Judaica gallery that opens on Dec. 8.

“Intentional Beauty: Jewish Ritual Art from the Collection” is the first Judaica gallery in an art institution in New England, according to the MFA. The dedicated space will showcase 27 ceremonial objects, including 20 works on view at the MFA for the first time — almost all of them new acquisitions.

The installation is thematically divided into three sections: objects for adorning and protecting the Torah scroll; artworks made for use at home; and ritual clothing which explores their gendered histories.

Beyond its extraordinary beauty, the collection stands out for its breadth and diversity, said Simona Di Nepi, curator of Judaica at the museum.

The ritual objects span centuries and come from across Europe, Asia, North Africa and the U.S.

“There is no one single prescribed style of Judaica,” Di Nepi emphasized in a conversation at the MFA where she and Gerri Strickler, the MFA’s objects conservator, showed some of the objects they were preparing for display.

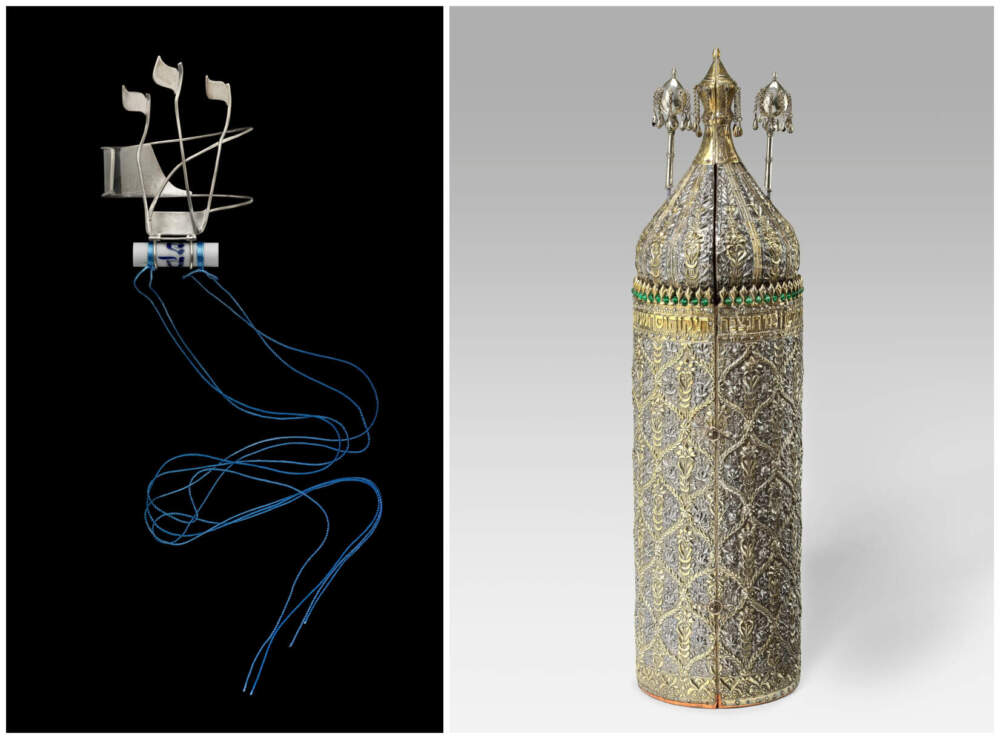

The array boasts rare Torah finials; a stunning, 19th-century Iraqi Torah case and a contemporary Hanukkah menorah. An elegant woman’s silver arm bracelet by Israeli artist Tamar Paley created in 2018 is one of several pieces that spotlight the shifts in religious gender roles.

The exhibition’s name, “Intentional Beauty,” alludes to the Jewish concept of enhancing rituals through aesthetics and beauty, Di Nepi, explained.

“The rabbis must have known that if something shimmers and gleams, you’re going to feel more spiritual,” she said.

Until now, Judaica has been integrated into fourteen separate galleries. It’s a curatorial approach the MFA adopted that afforded Judaica a prominent place with other decorative arts of their time, rather than separating Judaica.

As the MFA expanded its collection over the last six years, De Nepi envisioned a chance to embrace both possibilities. “Why do I have to choose?” she thought.

Notably, all but one work of Judaica will remain in their current location.

The gallery opens a new lens for visitors and students by presenting the objects from the global Jewish diaspora in their Jewish context, Di Nepi observed. It’s also an opportunity to present the museum’s new Judaica, carefully cultivated over the last six years.

There are benefits to both curatorial approaches, according Michael Zell, a Boston University professor and scholar of 17th-century Dutch art who's written extensively on Rembrandt’s portrayals of Amsterdam’s Jews.

“It's certainly helpful to see these objects interspersed with others from various cultures," he said. He’s pleased that a pair of rare 17th-century silver Dutch Torah finials will remain in the Dutch and Flemish gallery.

"But a dedicated [Judaica] gallery gives the public and scholars the larger context of the Jewish diaspora and a clearer sense of the riches of the collection."

For Di Nepi, highlighting the collection’s diversity was a priority.

This is most evident in the Torah finials, known as rimonim (pomegranate in Hebrew), that are found across cultures and geographic boundaries.

One exceptional pair was made in 1729 by Abraham Lopes de Oliveyra, a Dutch-born Sephardic Jew who settled in London, where he was the earliest known Jewish silversmith active in England, Di Nepi said.

These partially gilded silver rimonim made for a London synagogue feature tiers of bells that hang on an engraved stave, a distinctive mark of de Oliveyra’s style.

By contrast, a set of silver Iranian rimonim that date from the late 19th or early 20th century, feature a round, pomegranate-shaped bulb with engraved almond-shaped flowers and have tiny dangling stars.

“The decorative motifs speak to the artistic language of the country,” Di Nepi said.

The exquisite 19th-century Sephardic Torah case, made of wood and silver and partially gilt, was made in Baghdad. It was likely used by a synagogue in Kolkata, Di Nepi suggested, based on her research.

The recently acquired Torah case consumed some 100 hours of painstaking surface cleaning to remove dark silver tarnish and layers of old polish, Strickler said.

They are not restoring or covering up any wear, she explained, reflecting the MFA's approach to conservation that she described as intentional caretaking.

“We want to treat them with respect for their history. We are trying to hold that history and show it through the objects in as best a light as possible.”

“Intentional Beauty: Jewish Ritual Art from the Collection” is open to preview on the evening of Dec. 7, during the MFA’s public Hanukkah celebration, ahead of its public opening on Dec. 8.