The Boston Tea Party at 250: History steeped in myth

On a chilly December night, 250 years ago, a group of men destroyed a lot of tea.

The Boston Tea Party was an act of civil disobedience. The caper, led by disguised men on the ships and silently cheered on by thousands on shore, helped catalyze the American Revolution.

It's also a story historians say is filled with myth and a little mystery.

“The Boston Tea Party has been one of the most sensationalized moments in our nation's history,” said Evan O’Brien, the creative manager of the Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum.

The misconceptions vary from the “mildly inaccurate to just out of control,” he said.

For starters, the Boston Tea Party had very little to do with tax hikes. Despite the name, it wasn’t a party, much less a drunken party. And, party or not, the protest appalled some colonial leaders like George Washington and Benjamin Franklin.

But others had only praise.

“This is the most magnificent movement of all,” John Adams wrote in his diary the day after the tea was dumped overboard. “I can't but consider it as an epocha in history.”

There’s no denying the whole affair set the colonies on a path that led directly to the Revolutionary War and the birth of a new country.

Now, on the Boston Tea Party's 250th anniversary, O’Brien said it’s a good opportunity to look anew at what many consider the nation’s first peaceful protest and why it mattered — both then and today.

The tempest over tea

“If we were sitting in London in 1773, thinking about the empire, Massachusetts would be last on our list of important places,” said Robert Allison, a historian at Suffolk University. “We would be thinking about Barbados, Jamaica, and most importantly, India.”

At the time, the British East India Company controlled trade out of India. But there was a problem: It was in debt and about to go belly up. To bail it out, the British parliament gave the company a monopoly over the American market to sell tea.

This was the final straw for many colonists. They’d long been mad about taxes. But this particular move wasn’t a tax hike — to the contrary, it would have made tea cheaper in America.

Instead, they were upset they didn’t have a say in the decision.

“The tea is really a symbol of who governs us,” said Allison, who has written a book on the Boston Tea Party. “Are we now governed by a force we can't control?”

Coming to a boil

From South Carolina to Philadelphia and New York, colonists debated what to do when this cursed tea hit American shores. Quite by chance, the first tea-bearing ships arrived in Boston.

That started the clock ticking since ships had to pay duties on their goods if they were in port for more than 20 days. Colonists guarded the ship in 12-hour shifts to make sure nothing was unloaded.

Meanwhile, people had to figure out what to do next.

“Boston was boiling over with resentment, with anger, with confusion, with worry,” said O’Brien of the Boston Tea Party Ships and Museum. “Emotion was running rampant.”

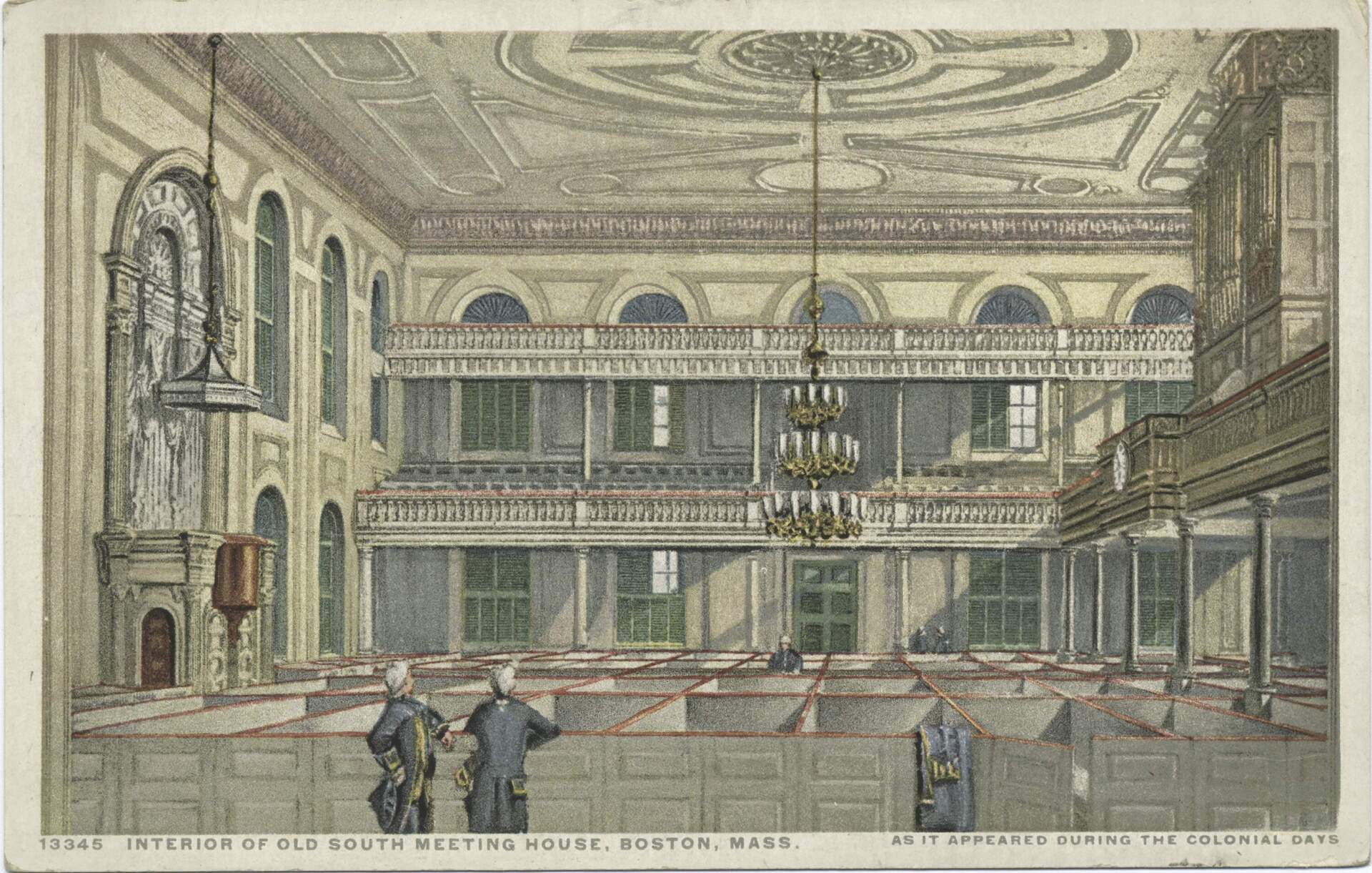

On Dec. 16, 1773, colonists converged on the biggest building on the busiest street in Boston: The Old South Meeting House. Today, the red brick building with an imposing steeple has a fire code that limits the space to 550 people max. On the day of the Boston Tea Party, preventive fire safety wasn't a priority.

Advertisement

“The eyewitness account said there were 5,000 people in this space,” said Nat Sheidley, the CEO of Revolutionary Spaces, which oversees the historic building. “That's 5,000 people in a town of 15,000, right? So a third of the town crammed in here like sardines.”

People hung off the balconies and spilled out into the streets, he said.

As night fell on the ships' 20th day in port, the crowd in the meeting house got a new bit of intel: The pro-British governor said the ships full of tea could not return to England, and the tea would have to be unloaded.

That's when revolutionary leader Samuel Adams stood up and said: “This meeting can do nothing more to save the country!” Reports from the time say this was met with war whoops.

“Some people believe that was a secret signal to rally the Sons of Liberty, who had made all kinds of plans about what to do with the tea if it was not going to be sent back to England,” said O’Brien.

Getting the party started

More than 100 men marched to nearby Griffin's Wharf, where the boats were tied up. Some of the men in this procession came from a local tavern, though historian Allison said there’s no evidence they’d been drinking.

When they got to the wharf, they asked permission to go on board the three tea vessels, said O’Brien.

One of the ships had a pacifist quaker captain from Cape Cod. He allowed the men aboard, and he even let his crew participate in the protest if they wanted.

Despite the civility, everyone was well aware this act of civil disobedience was a crime — and they took precautions.

“This meeting can do nothing more to save the country!”

Samuel Adams

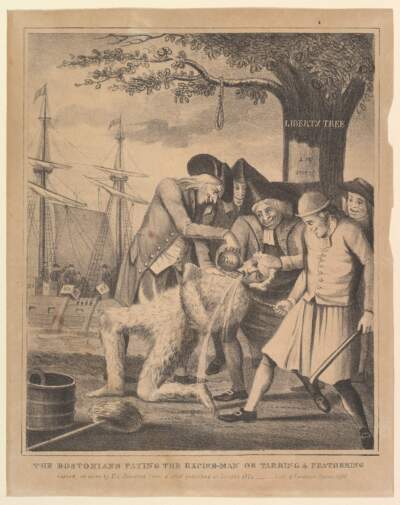

Many men wore blankets and put soot on their faces to hide their identity. Despite later images and paintings, historians say there were no feather headdresses worn, although some of the men were loosely disguised as indigenous people.

“It's just a very quick disguise they're putting on … to give them an ability to deny that they actually were part of this,” said historian Allison. “They're committing something that could be high treason.”

The men who boarded these ships and took on this grave risk weren't the more famous Sons of Liberty members, remembered in history books and paintings. These were generally ordinary citizens: wallpaperers, house painters, shipwrights, barrel makers, cobblers, coopers.

“Meanwhile, back at Old South [Meeting House], Samuel Adams, John Hancock, Dr. [Thomas] Young, the real leaders of this movement, are still there giving speeches,” said Allison. The speeches were essentially an alibi, he said, “when the news accounts come out, they can say, ‘Well, this is where we were.’ ”

Myth vs. reality

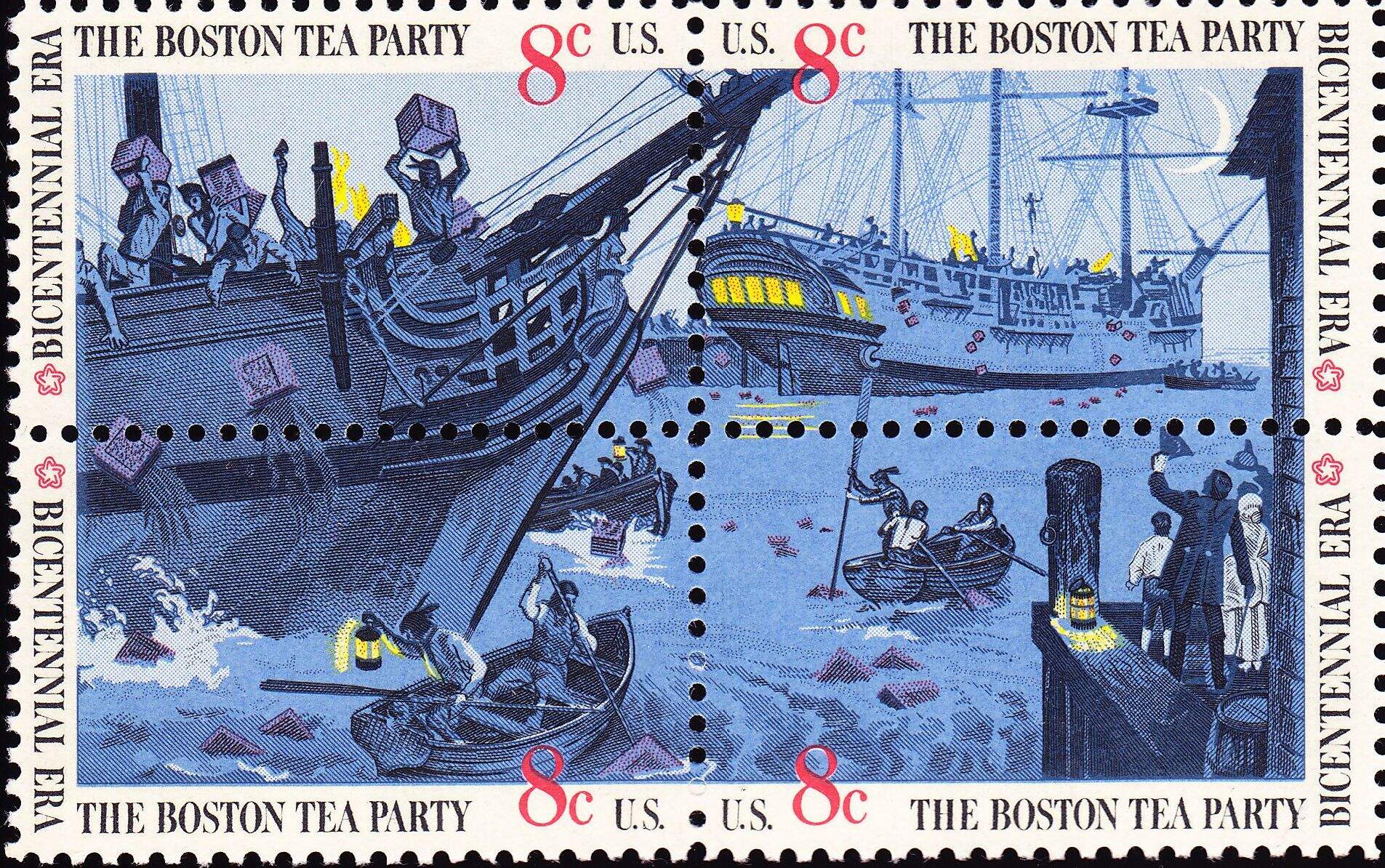

Here comes the part of the story that everyone agrees on: The patriots hauled chests of tea out of the cargo holds of three ships, broke them open with axes, and chucked the tea and crates overboard into the chilly Boston Harbor.

The less glamorous part of the story is that it was low tide, and mounds of tea started to pile up.

“The vessels were literally resting in the muck and the mud of Boston Harbor. And so much tea was going over the side that some anecdotes claim that the tea was beginning to pile up as high as the sides of the ships,” said O’Brien. “So they would send people, specifically the apprentices, over the side to smash the tea down. Other people, it said, came over in canoes and boats to smash the tea into the surface of the water to thoroughly ensure its destruction.”

Despite the smashing, and the event's "party" branding, it wasn't a raucous affair. Instead, historians describe it as disciplined, methodical, carefully planned.

“A crowd does come and watch this happening on the docks, and people comment on how orderly they are, how quiet they are,” said Allison.

The focus was making a political statement. None of the other cargo was disturbed and nothing was stolen, he said.

The colonists even swept the ships clean once all the tea was destroyed.

“Someone broke a padlock on one of the ships. They send someone into town to get a new one, to replace it,” said Allison. “And I have to confess Bostonians did tend toward a lot of street violence in the 1760s and 1770s, which makes this so much more remarkable.”

“It was said that following the last tea chest going in the water that Boston had never been that quiet before,” said O’Brien. “It's almost like the entire town knew that they had crossed a threshold and everyone was holding their collective breath.”

A wicked post-party hangover

As the sun rose that next morning, loose leaf tea was still washing ashore. People walked the beaches collecting the salty leaves to keep as souvenirs.

“They knew it was a momentous occasion,” said Jonathan Lane, the executive director of the Massachusetts-based group, Revolution 250.

As word spread about the 92,616 pounds of tea that were destroyed — worth more than $1.5 million today — not everyone was on board.

“George Washington and Benjamin Franklin think they really went too far. Washington is kind of aghast at this destruction of property,” said Allison.

The British parliament was also aghast.

It reacted strongly, shutting down the port of Boston, which crippled the local economy. It also suspended town meetings and local elections. In the colonies these responses and others were known as the Intolerable Acts.

“What Massachusetts does is actually calls for a meeting of the other colonies, which is a huge risk,” Allison said. “It could be the other colonies will say, ‘You wacky Puritans really went too far this time.’ ”

But they didn’t. Instead, the colonies were shocked by the British reaction and rallied in support of those Puritans.

“You have people in Connecticut sending droves of sheep up to Boston. People sending fish or other goods from other colonies,” said Allison.

Tea-soaked omerta

Despite the Parliamentary fury, the men who perpetrated the Boston Tea Party were not punished.

This is partly because after the events, “the prosecutor leaves town,” Allison said. “He doesn't want to have to try to prosecute anyone for this, knowing which way things were going.”

But mostly it's because the men on the ships and the onlookers on shore maintained a remarkable silence.

Only decades later — long after the colonies had become a country — was the silence broken.

By the early 1800s, the participants were getting old and “they started telling their stories to their grandchildren and their sons and their daughters,” O’Brien said. “And that's when these rumors and these lists began to be compiled.”

It was also around that time that the term “Boston Tea Party” started to be used; it had previously been cumbersomely described as “the destruction of the tea.”

Teaching tea's lessons

But even today, with its official name and wide-spread fame, there’s not a complete list of the men who took part in dumping the tea into the harbor.

The Boston Tea Party Ships and Museum has worked with genealogists to comb through old documents to figure out who participated and then mark their graves. So far, they’ve traveled to 10 states and three other countries to mark headstones and hold ceremonies.

O’Brien said some Tea Party descendants have come forward, and so has the general public. It’s the busiest year in the museum’s history.

For O’Brien, that’s an opportunity.

He and others hope the anniversary helps people remember the Boston Tea Party for the civic engagement, for the insistence on representation in government and for the discipline shown by the protesters who dumped the tea 250 years ago.

“There's much we can criticize about the past, but there's also much to admire — and certainly the events around the Boston Tea Party are among those to be admired,” said Lane.

This segment aired on December 15, 2023.