Advertisement

Mass. cities, towns cautious or confused about how to spend millions in opioid settlement funds

Money from the settlements of opioid-related lawsuits continued to pour into Massachusetts in 2023. While the state is spending its share on programs aimed at reducing substance use and fatal overdoses, the majority of cities and towns have not spent any of their funding.

The state collected $23 million in 2023, for a total of $106 million since 2021. Municipalities began receiving their first settlement payments in the fiscal year that ended in June, and have banked a total of $51 million so far. The biggest cities — Boston, Worcester, Springfield and Cambridge — are receiving the largest shares.

But forms filed by cities and towns show that most had not spent any of the money received in the first of a nearly two-decade distribution plan. This has frustrated some observers who urged faster action as opioid-related overdose deaths hit and held at record highs.

Boston reported taking in $4.7 million, but made $0 expenditures. The city said it was reviewing input collected from listening sessions and more than 400 surveys submitted by residents and addiction services providers. Boston plans to announce spending strategies in early 2024.

Cambridge banked $1.9 million in settlement funds. A community survey about how to use the money is still open, although a spokesman for the city said officials have decided to buy an outreach van.

Worcester is one of the few municipalities that spent all of its first-year payments, worth $845,000. As the settlement dollars started to arrive, the state’s second largest city was in the midst of a 34% increase in overdose deaths from 2021 to 2022. A city spokesman said $500,000 of the funds paid for a mobile crisis team to help respond to 911 calls involving mental health and substance use. The balance of the funding covered staff that provides outreach for people struggling with homelessness and substance use.

In New Bedford, officials received $1 million in first-year payments but didn’t spend any of the funding. Stephanie Sloan, the city’s health department director, said it will take time to determine how best to use the money.

“The amount and duration of the funding requires a deliberative and strategic process as we all seek to build on the extensive work and programs already underway to respond to the opioid epidemic,” she said in a statement.

Other cities with high numbers of fatal overdoses also reported no expenditures even though they received substantial sums. They include Springfield, which got $1.5 million, Lynn received $704,000 and Lawrence got $653,000.

Some municipalities said state accounting rules complicated their efforts to spend the money, but they hope an exemption now in place will ease the process.

“Going forward we can receive these funds directly into the opioid settlement fund account,” said Lindsay Hackett, Springfield’s deputy chief administrative and financial officer. “So we can track exactly what’s going in and coming out.”

Hackett said Springfield used some general city funds for police staffing and training for the police and fire departments on Narcan, a brand of the overdose reversal drug naloxone.

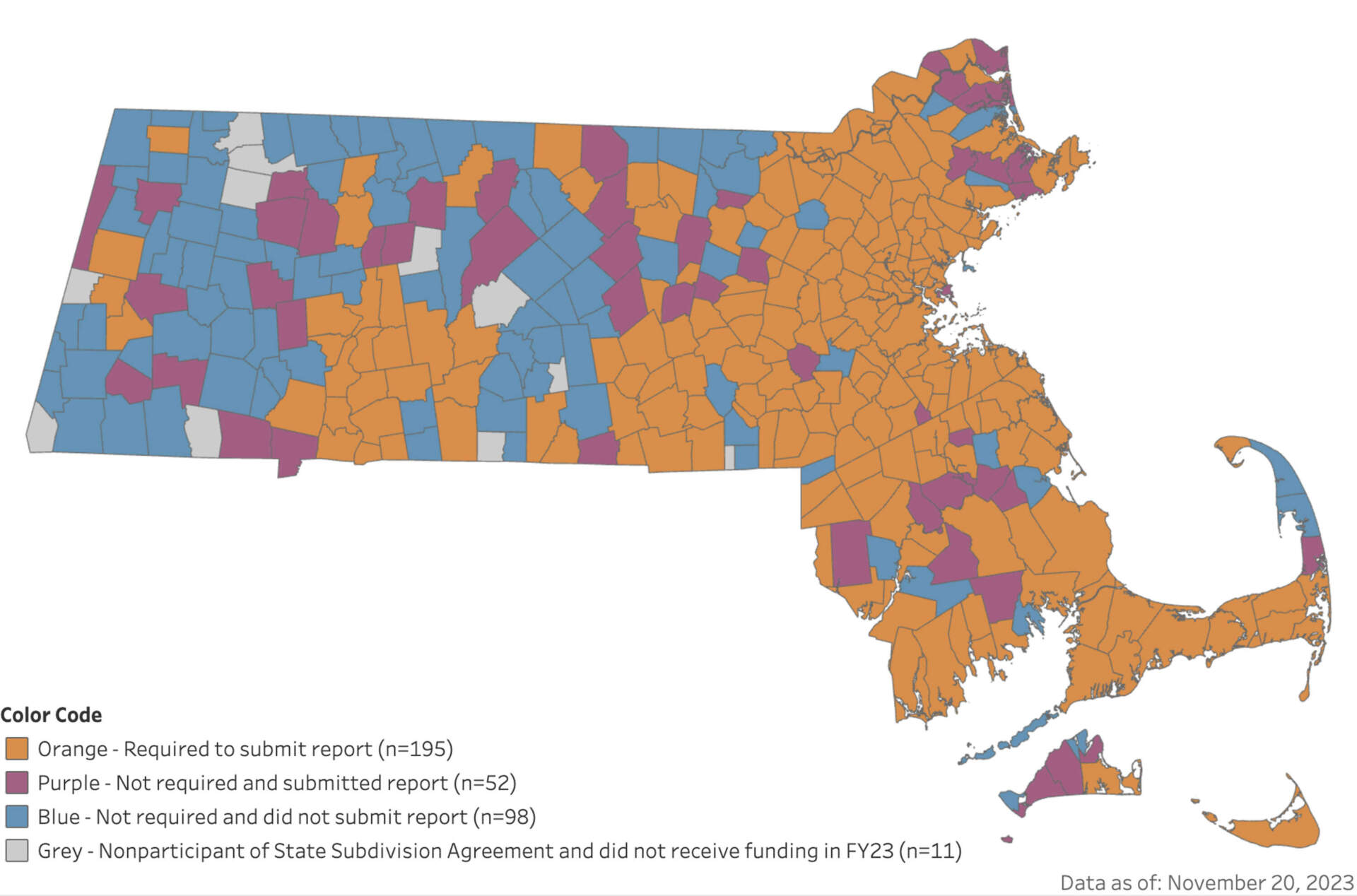

Some municipal leaders may have little or no experience with addiction treatment and policies. A quick scroll across the state map shows dozens of smaller cities and towns sitting on payments that total millions of dollars. That's frustrating for many people who track opioid-related overdoses and deaths.

“It's disappointing and distressing to see so much money sitting on the sidelines while we face this surging opioid overdose crisis,” said Jonathan Stoltman, director of the Opioid Policy Institute, in a statement. “We know too much about what works to not do anything.”

Dr. Kiame Mahaniah, Massachusetts undersecretary for health, said many municipalities aren’t aware the money is coming in or that it must be used to address the opioid overdose crisis.

“A city might think, ‘what can I do with $100,000,’ but this is something that will continue for 20 years, so it does behoove a community to get involved deeply on the front end,” Mahaniah said during a meeting where he shared initial reports from municipalities.

The state has hired a consulting firm to assist cities and towns, but it doesn’t control how they use the money from opioid distributors, manufacturers and other companies that allegedly helped fuel the opioid crisis. Municipalities will receive roughly 40% of the settlements reached to date.

The state is spending its share of settlement funds more quickly, with guidance from an advisory council that includes physicians, public health leaders and advocates for people affected by the drug overdose crisis. The group set five priorities, which the Healey administration has tied to grant proposals with specific dollar figures.

- Equity — $10 million for community advisory boards, research and prison re-entry programs to address racial disparities in overdose deaths.

- Treatment — $18 million for walk-in clinics and addiction specialists in 15 hospitals that serve high need areas, and more money for a stimulant addiction treatment approach called contingency management.

- Workforce Development — $15 million to support loan forgiveness and other incentives administered by the state’s Behavioral Health Trust Fund.

- Family Support — $3.5 million for families coping with addiction and those who’ve lost loved ones to an overdose.

- Data Collection and Analysis — $2 million for a dashboard that may expand to include real-time overdose data, opioid-related hospitalizations statewide and community-specific.

The state has received about 17% of the total expected over 18 years of settlement payments. Municipalities have received about 13% of their expected funding.

Some additional dollars could flow from lawsuits against members of the Sackler family and Purdue Pharma. Those cases were consolidated in bankruptcy court, but a settlement was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court by parties that object to immunity for some Sackler family members.