Advertisement

Field Guide to Boston

What the heck is graupel? New England winter weather terms, defined

New England winters can be a particular kind of beast. They bring a slurry of snow variations, high winds, freezing cold temperatures, early afternoon darkness and strange environmental alterations to our infrastructure. (see below: "ice dams," "frost heaves," etc.)

It's not all bad, though; winters in the Northeast can also bring beauty, warmth (by proxy, at least), adventure, and breath-taking phenomena. If you're from the region, we're sure you've heard — and likely used — some of the winter terminology below. However, if you're new to our six-state section of the country, some of these terms may have you scratching your beanie-covered head. Other terms may just bring winter awareness that can save you a lot of money in home repairs (again, see "ice dams" below ... seriously, they're the absolute worst).

A quick disclaimer that these terms below are not necessarily exclusive to New England, but we certainly do experience them.

New England Winter Terminology

Winter Precipitation:

Snow "flurries" vs. snow "showers" vs. snow "squalls"

Believe it or not, they are different. You'll hear these terms when watching or listening to the weather forecast. It really comes down to accumulation and winds. Flurries are really the nicest and most picturesque version of snow you can get, with little to no accumulation. Showers bump up the intensity and usually leave snow on the ground. And squalls are quick, dangerous, and can bring thunder and lightning (see "thundersnow" below).

Graupel

A strange phenomena often referred to as "soft hail." Yes, you read that right, soft hail. It usually occurs in the right conditions during a thunderstorm. According to 9News in Colorado (a brethren state of wintery happenings), it's technically not hail or snow, but it's own entity — "kind of a combo," the news station says.

Sleet vs. freezing rain

Just like the whole flurries, showers and squalls conversation, these are actually individual types of precipitation. According to the National Weather Service, "sleet occurs when snowflakes only partially melt when they fall through a shallow layer of warm air." They then fall through a thick layer of freezing air and reach the ground frozen — sleet can even accumulate like snow.

Meanwhile, "freezing rain occurs when snowflakes descend into a warmer layer of air and melt completely," states the National Weather Service. The droplets then move through another thin layer of freezing air but don't have time to refreeze before impact — they do, however, refreeze as soon as they come into contact with a surface 32 degrees Fahrenheit or below. When refreezing, they can create a frosty glaze that commonly takes down trees and power lines. Enough freezing rain leads to an ice storm (see below).

Storms:

Blizzard

Not the delicious ice cream treat from Dairy Queen. No matter where you're from you've probably heard of a blizzard. Technically, for a snowstorm to be a "blizzard" it needs to meet the following requirements:

- The snowstorm conditions are expected to last for three hours or more

- The storm has sustained wind or gusts up to 35 miles per hour or greater

- Significant snow precipitation that reduces visibility to less than a quarter of a mile ahead

Famously (and frequently) you'll hear folks in New England talk about the Blizzard of '78. Despite the constant reference, it really was insane.

Nor'easter

A storm with strong northeast winds that moves along the east coast of North America, typically hitting maximum strength in northeast of the United States and into Canada. They almost always bring "precipitation in the form of heavy rain or snow, as well as gale force winds, rough seas and occasionally coast flooding," according to the National Weather Service.

Although these storms can hit any time of year, nor'easters are responsible for some of the most famous winter storms to hit New England. Yes, that includes the Blizzard of '78.

Ice storm

Simply put, it's cold here and when we get enough freezing rain (see above), we get ice storms. Specifically, significant ice accumulations of 0.25 inches or greater equates to an ice storm. These usually brings down tree limbs, power lines, freezes over streets and causes extreme chaos for any type of commute at any hour. We don't want to editorialize here, but they're awful.

If you're feeling curious, the National Weather Service has an incredible summary of the crippling ice storm of '98 that affected New England, parts of New York, and southeast Canada.

Thundersnow aka "White Lightning"

Lightning plus thunder plus snow equals "thundersnow." These storms are rare, but once in a blue moon you can catch a thunderstorm dropping some snow — and they aren't exclusive to the New England region. Apparently some meteorologists get really excited when they do happen to experience it, like The Weather Channel's Jim Cantore:

Here's the quick science behind it: "Thundersnow can be found where there is relatively strong instability and abundant moisture above the surface, such as above a warm front," according to the NWS.

Snowmageddon, Snowpocalypse, and/or Snowzilla

Let us take you back to 2013, back to a storm The Weather Channel called "Nemo." And no, it wasn't looking to be found — instead, it kicked in the region's door with vengeance, combined with another storm, and dumped more than two feet of snow on us. And thanks to wild winds, snow drifts towered over nine feet tall. The storm shut down the highways and the MBTA, and everyone did their best to hunker down. You could even serve jail time if caught driving around in it. Cars were completely covered. It even looked insane from a satellite's perspective. Still, some folks think the Blizzard of '78 was worse

And this kind of thing is, unfortunately, not uncommon. In 2015, there was so much snow during our winter months, it didn't fully melt until July. Hence, any of the ridiculous names you may hear on a forecast update, like "Snowmageddon."

TLDR: Although a bit sensational, if you hear any of these terms discussed in an upcoming forecast, you should probably be paying attention and preparing.

Honorable mention: Polar vortex

This is a term that has existed for a long time, but has only recently been used consistently in media coverage of extreme cold in the winter months, according to the National Weather Service.

"Polar vortexes are not something new," according to the NWS. "The term 'polar vortex' has only recently been popularized, bringing attention to a weather feature that has always been present."

But what actually is it? It's not a storm (hence the "honorable mention" tag), but a cold outbreak on the planet near the poles — specifically, an area of "low pressure and cold air" that strengthens in the winter time, according to the NWS. These arctic blasts differ in strength, but here in New England we have feel them. Basically, it's just another way of saying we experience some extreme frigid temps. And if you hear about it on weather coverage, bundle up.

Hazards:

Frost heaves

Frost heaves are the polar opposite cousin to potholes (which every New England driver knows about) and offer an easy way to devastate your vehicle. These are humps that vary in size that form in the roads during the late winter. There's much more science to it, but to simplify things, frost heaves occur from water freezing within soil in the ground, which creates a usually-hard-to-see bump in a road.

Unlike a pothole — where there would be a recess in the ground destroying your car's tires — instead, there's a inauspicious bump that will destroy your suspension and potentially smash your head into your vehicles ceiling. Words to the wise — if you see a sign signifying frost heaves ahead, slow down and drive cautiously.

Black ice

This type of ice is sometimes called "clear ice" and is invisible on a street surface. Commonly found on asphalt, hence the term "black ice," this hazard can cause issues on the road and often tumbles over its fair share of casual winter pedestrians. It typically forms right around the freezing temperatures — look for a glossy sheen over a surface if you suspect an area may be slippery.

Driving over black ice is the true challenge. According to the U.S. Forest Service, the key to navigating over black ice in a vehicle is to first remain calm.

"The general rule is to do as little as possible and allow the car to pass over the ice," according to the U.S. Forest Service. "Do not hit the brakes, and try to keep the steering wheel straight. If you feel the back end of your car sliding left or right, make a very gentle turn of the steering wheel in the same direction."

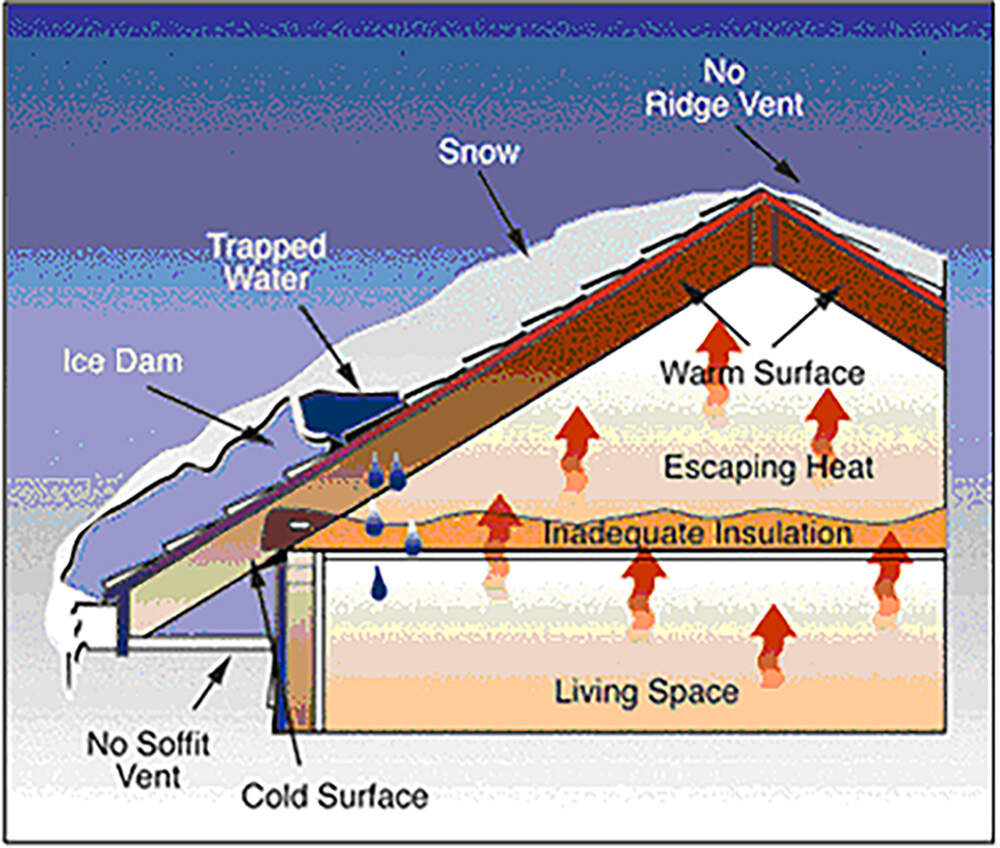

Ice dams

A home owner's true nightmare and silent destroyer, ice dams are a buildup of snow melt that then refreezes on your roof, under shingles or in your gutters. If these dams continue to melt and refreeze, they can cause considerable damage to your home's roof, siding, ceilings, and walls. And worst of all, you may not notice until the damage is already done and you realize areas of your home are compromised and leaking water.

To avoid ice dams, do your best to keep your gutters clear of debris, especially since winter can move in swiftly behind autumn with leftover leaves and sticks in those areas. The National Weather Service has a great rundown of preventative actions to reduce the chances of ice dams for home owners.

Frost quakes (aka cryoseisms)

These rare phenomena are similar to earthquakes, but caused by extreme cold temperature drops and are highly localized. Water in the ground suddenly freezes with a sharp temperature drop, it expands, and if the stress causes ground to crack it will create a loud force similar to a localized quake.

Despite how scary this may sound, these frost quakes are small potatoes compared to an actual earthquake, and release a much smaller amount of energy in comparison.

According to the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation & Forestry, "in some cases people in houses a few hundred yards away do not notice anything."

Winter Phenomena:

Snow rollers

If tumbleweeds could be snow-based, that's what would best define a "snow roller."

If you see one of these, you've seen on of the rarest winter phenomena out there. Everything needs to be in place. The right geography needs to be around, as well as the right temperatures at the right times. This Canadian public radio broadcast does a great job on how these rare rollers form and under what circumstances you could see them.

Sun dogs & Light pillars

Consider yourself lucky if you can catch the winter show that consists of either sun dogs or light pillars. This rare combination of sunlight and ice crystals can create beautiful colors in different forms throughout the sky — sometimes in the visual of orbs flanking the sun, aka sun dogs, or as stark rainbow columns cutting through the sky, aka light pillars. It all just depends on the sun's positioning.

Rime ice

A frost that comes via fog, rime ice leaves a unique look to the objects it covers.

"Rime is a deposit of interlocking ice crystals formed by direct sublimation on objects, usually those of small diameter freely exposed to the air, such as tree branches," says the National Weather Service.

Ways to say "It's cold!":

Brisk

Not exclusive to winter and often used to describe autumn weather. Wintery temperatures can start creeping in around October, and many New Englanders will comment on the "brisk" air. Typically, this is an enjoyable drop in temperature. A calm before the theoretical New England ice age.

Frigid

A term used by New Englanders when it's actually cold and uncomfortable. Temperatures have dropped to an unfortunate low, and adding a hat and gloves or mittens to your daily outfit is usually warranted. There's a stronger intensity to the term "frigid" that many New Englanders will immediately pick up on.

Brick

Simply put, it means unbelievably cold. Like a brick of ice. Who coined it? It may have been Millennials, it may have been Gen Z, who's to say? Do we feel silly saying it? Again, who's to say?

Three-dog night

In contrast to "brick," we have a very old-school saying here that means just about the same thing: It. Is. So. Cold. So cold, that you need three dogs in your bed with you to keep everyone warm throughout the night. Some say the phrase originated in Siberia, others point to Alaska.

Three dogs is the maximum amount of dogs in the saying for reasons we don't understand — a one-dog night implies it's cold enough for just one dog. We say bring all your dogs into bed and stay warm together — spring will be here before you know it.