Advertisement

Review

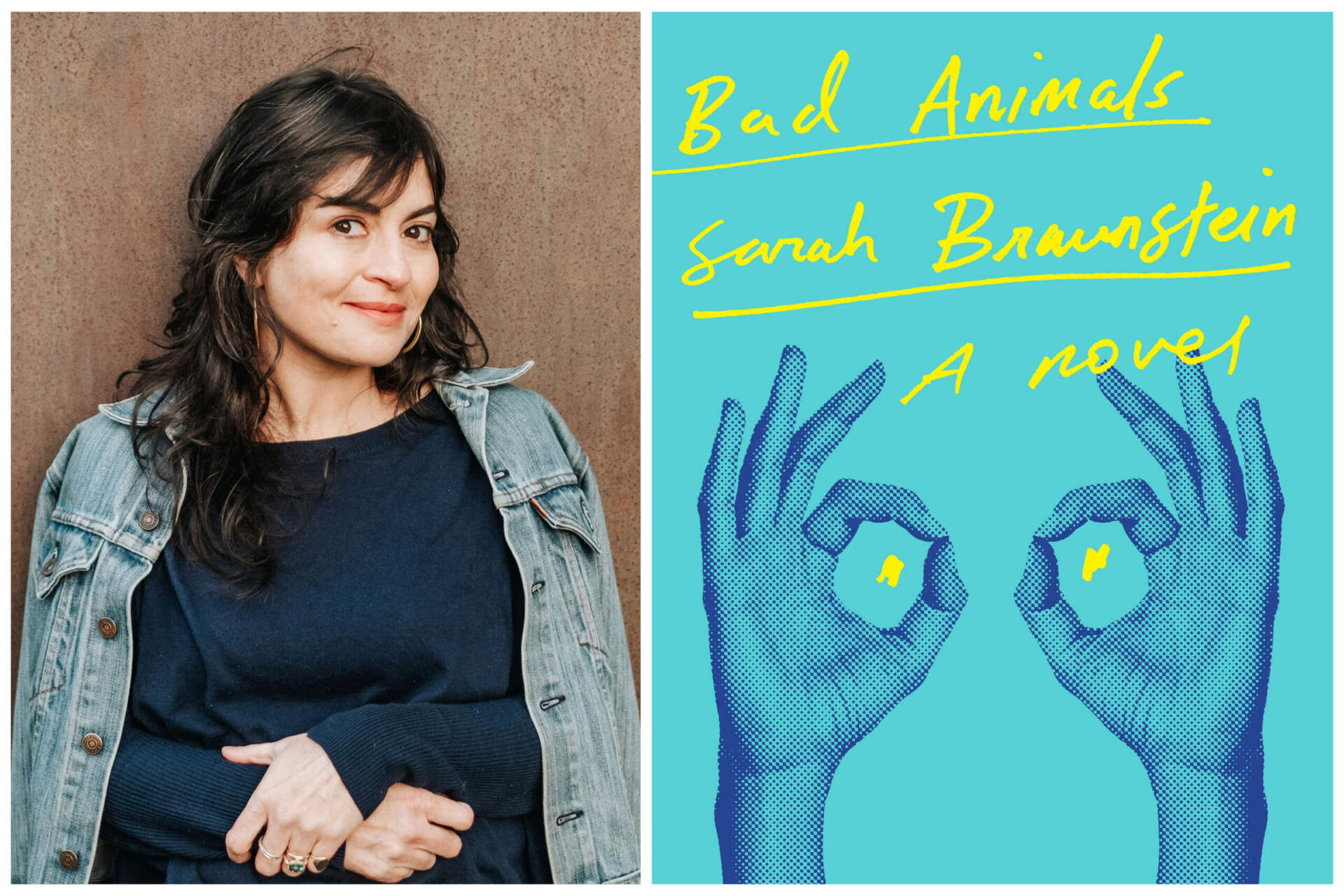

Novel 'Bad Animals' questions the stories that are told

At the start of “Bad Animals,” Sarah Braunstein’s uneven but quite clever novel, a pleasant workday at a small-town library quickly goes bad.

Maeve Cosgrove, the library’s longtime cultural coordinator, is accused by 16-year-old Libby of spying on the teenager having sex with a boy in a library bathroom stall. Benefiting from a reputation as being reliably uninteresting, Maeve is ultimately cleared of the accusation (Libby is deemed “a very troubled kid telling stories”). And yet, soon after, Maeve is laid off.

The two incidents, which may or may not be linked, touch off a series of unexpected events. Unmoored by the shock of her job loss, Maeve begins to question herself, her marriage and her friendships. She wonders, “What else am I not seeing?”

As a reader, you would do well to ask yourself the same question. It’s not that Maeve is a completely unreliable narrator, but she is a disingenuous one, recounting a set of months that proved transformative for certain residents of this coastal Maine town.

Harrison Riddles, a seasonal resident and Maeve’s favorite author, has recently agreed to appear at the library for a book reading. Maeve had previously laid the groundwork for this; now her friend and coworker Katrina will reap the benefits. Not only that, Harrison wants to write a book about Katrina’s boyfriend Willie, a Sudanese refugee who came to Maine as a young boy.

Soon Maeve, who till now had enjoyed a steady if lackluster marriage, embarks on an affair with the smooth-talking, self-deprecating writer. For Harrison, this is business as usual; he and his wife have an open marriage. For Maeve, it’s exhilarating. Beyond the bedroom adventures, she’s thrilled to be a sounding board for this renowned author as he ponders how to best convey Willie’s story.

With Willie’s book as a key plot element, “Bad Animals” has the quality of a novel within a novel. This framework enables Braunstein to implicitly pose the questions: Who gets to tell your story? Whose stories can you trust?

Advertisement

Harrison is torn between framing Willie’s story in the first person (he considers this style a “lie fueled by truth”), or in a safer, more removed third person. Throughout, Braunstein skillfully shows who in this community, like Harrison, is allowed a dominant voice, and who, like Willie or the teenager Libby, might be robbed of that power.

With an ambitious array of plots — including the original library tumult; the changing dynamics in Maeve’s own marriage; and one involving their precocious college-age daughter and her science-fiction-like botany research that could have international repercussions — Braunstein uses the calendar to ground the action, with many chapters or sections beginning with a specific month and day. This augments a sense of people moving along a fated timeline, who cannot help but behave according to their true, primal nature. Still, some storylines sag a bit before regaining a narrative foothold, and others that initially seem important simply fade into the background.

Signaling complications ahead, the beginning of the book bears an epigram by Dostoyevsky, on how cruelty in humans is often described as “bestial,” but that “No animal could ever be so cruel as a man, so artfully, so artistically cruel.” It’s not that this busy cast of characters is intentionally malicious, but their matter-of-fact deceptions to further their own interests do edge toward callousness.

“Bad Animals” is Braunstein’s second novel, after the 2011 “The Sweet Relief of Missing Children.” Her short stories have appeared in publications including The New Yorker and The Harvard Review. A native of New England, Braunstein lives in Portland, Maine and teaches at Colby College.

In a book with supple writing throughout, this writer also evokes the state’s climate and its landscape in singular ways. For example, Maeve muses that winter “cracked her skin, scored her lungs – a whole life here didn’t inoculate a body.” Harrison and his wife enjoy decorating their palatial midcoast home with flea market and Goodwill finds; that “had been one of the appeals of Maine, in fact, a state of old people discarding their treasures.” Even a brief description of driving through a rainstorm is nicely layered: “A truck passed, and for one harrowing second the windshield was a gush of blinding white froth, then the road again, rippling darkness, the miracle of reflective strips.”

It’s a credit to Braunstein’s craft that this tale, filled with incisive observations and often amusingly unflattering revelations about a few primary players, is also leavened with tenderness. With Maeve as teller of this tale, Braunstein plants just enough seeds of doubt, prompting you to frequently reconsider the actions of other characters as well. This makes for a slightly off-balance read, in quite an energizing way.