Advertisement

Review

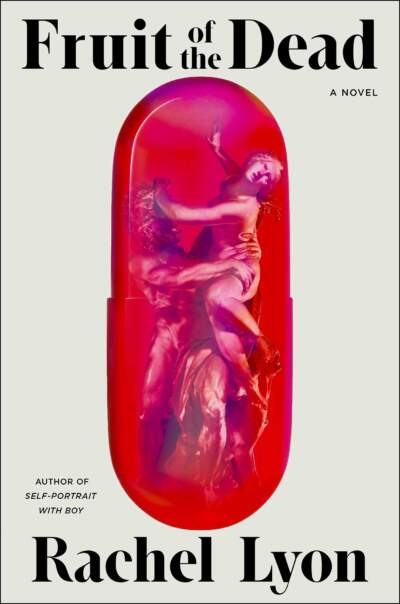

Novel 'Fruit of the Dead' is a contemporary reimagining of Persephone

In the follow-up to her debut novel “Self-Portrait With Boy,” western Massachusetts-based author Rachel Lyon reaches back into ancient myth for “Fruit of the Dead,” reimagining the story of Persephone as a contemporary parable about power, consent and trauma.

Cory Ansel is barely 18 and working as a camp counselor when Rolo Picazo crashes into her life. In an instant, she feels the alluring weight of his gaze. “The man’s focus on her is so intense,” writes Lyon, “she feels it like a tickle at the back of her neck, in her belly, in her you-know-what… a pleasurable feeling that is not a sign of pleasure, not exactly.”

The wealthy father of one of her campers, Rolo offers Cory a lucrative gig as a nanny for the summer, with a thinly veiled implication of something more — a job at his Fortune 500 pharmaceutical firm, maybe, or possibly a place in his life (or at least his bed). With no clear plan for her future and a strong desire to avoid her overbearing mother, Emer, Cory throws caution to the wind and follows Rolo to his exclusive island hideaway.

Though “Fruit of the Dead” is billed as a modern retelling of the myth of Hades, Persephone and Demeter, the references are mostly faint echoes. At times they can be corny and awkward, as when we discover that Rolo’s three guard dogs are named Serita, Bertie and Ursula.

Rolo himself doesn’t particularly resemble Hades or Pluto so much as he feels like a composite of tormentors from our contemporary living hell: Part Trump, part Sackler, part Epstein. He’s a rich, pill-pushing hedonist, a sexual predator with a private island and a penchant for young girls. And despite his corpulent bearing and vulgar demeanor, he supposedly exudes a kind of grotesque charisma that has allowed him to skate through life consequence-free.

As for that charisma, we have to take Cory’s (and Lyon’s) word for it — though they attest to Rolo’s magnetism, he’s never anything more than repellent on the page. It would be a stretch to claim that Rolo displays even a superficial charm; from the jump, his self-satisfied attitude and dime-store philosophizing, the crude way he treats and speaks about his children, and his boundary-violating, possessive treatment of Cory mark him as bad news.

That Cory ostensibly consents to allow Rolo, a complete stranger, to spirit her away to his remote island on a whim would seem to mark her as an oblivious naif, or perhaps so arrogantly assured of her 18-year-old wisdom that she’s blind to the veritable parade of red flags that are waving wildly right in front of her face. Her mother goes so far as to describe Cory as “gullible, reckless, aimless, and naive.”

In truth, the reality is much darker than that. On some level, it appears that Cory is fully aware of what she’s getting herself into and courts the danger intentionally. Her decision (“a corporeal acquiescence… natural and strangely physical, as if he had her on a leash”) is, in essence, a form of self-harm, which she pursues as a means to hurt her mother by proxy. Cory wants to make her mother pay for a devastating past transgression in which Emer, who raised Cory on her own, abdicated her responsibility to her daughter. It was a profound failure that shattered the bond between them, perhaps irrevocably.

“Whatever he might want with her,” Cory thinks, “fear is better than boredom… danger trumps familiarity, the unknown always more interesting than the known.”

On Rolo’s island, things unfold as you would expect. He plies Cory with drugs and alcohol, dazzles her with luxurious gifts and gives her a taste of his high-flying lifestyle while treating her in equal measure like a child, a romantic partner, and an indentured servant. There are hints that Cory’s not the first young woman to occupy this position, and along the way she learns more about Rolo’s personal and legal troubles, which threaten his company, his wealth and, perhaps most importantly, his self-image. Meanwhile, Emer, who runs an environmentally conscious agricultural NGO that is on the verge of collapse, abandons her professional responsibilities to set off on an epic search for her wayward daughter in the hopes of making things right.

Lyon relates this often troubling story in gorgeous prose that’s so vivid and luminous it contrasts starkly with the darkness of the subject matter. Every sentence is a feast, tempting you to push on further even as the discomfiting action of the plot and the often frustrating, deluded, self-defeating characters conspire to push you away.

“Eighteen years I’ve spent pursuing this maddening girl,” Emer thinks, “but like a creature in a fairy tale she’s metamorphosed even as I’ve taken aim. The deer shrinks and rises, flapping, soaring: a seabird. The seabird dives into the ocean, swims away: a fish. Well, let my bow and arrow become a harpoon, then. Let my harpoon become a net. Let me, her mother, be the hunter who saves her from herself.” Readers may find Lyon’s characters as exasperating and elusive as Emer finds Cory.

There are no easy answers for Cory, Emer, or even for Rolo. No neat and tidy conclusions, even if it might appear that one has come to pass. Lyon closes the book in an ambiguous rush of feeling and fury that comes across as neither triumph nor tragedy. Or perhaps it’s some tainted mixture of the two. It would be hard to call “Fruit of the Dead” a satisfying read; but perhaps there’s a bit of ugly truth to be found in its imperfect protagonists and dizzy, disorienting denouement.