Advertisement

Field Guide to Boston

'Live from the Underground' details the influential world of college radio

In “Live from the Underground: A History of College Radio,” author Katherine Rye Jewell takes readers on a deep dive into the amusing, anarchic and surprisingly influential world of student-run radio stations, exploring what made those left-of-the-dial broadcasts so special during the 1980s, ‘90s and 2000s.

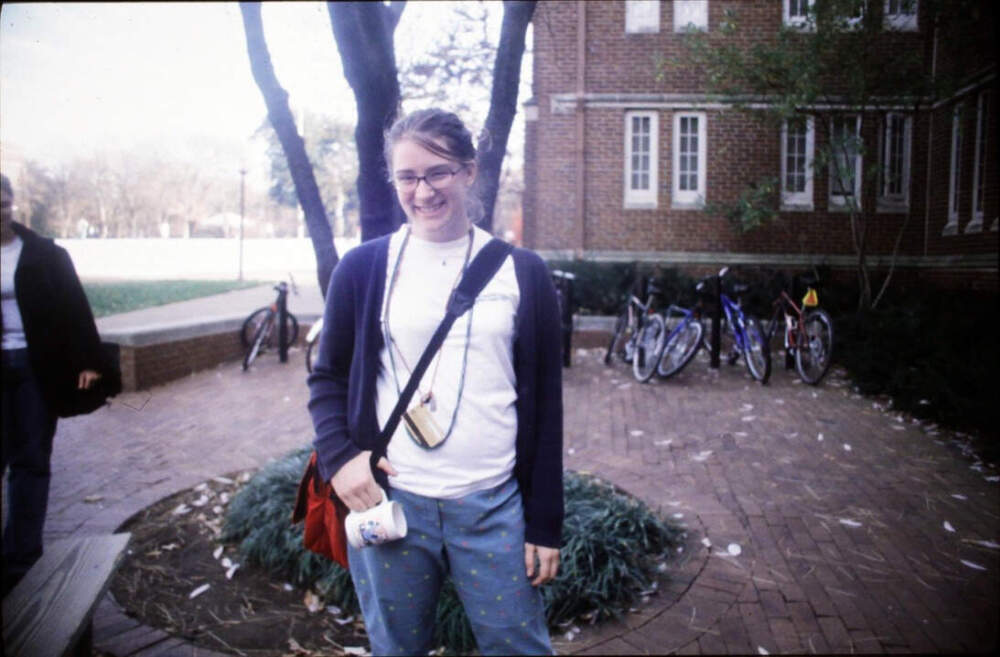

Jewell, a professor of history at Fitchburg State University, attended Vanderbilt University in the late 1990s and served as indie rock music director at its student-run radio station, WRVU. Growing up in rural Vermont, she’d had little exposure to college radio and was excited at the prospect of getting on the air. “When I discovered that I could be on the radio, I thought that was the coolest thing ever,” Jewell said. “And it was a way for me to enter into this world of underground music that I had never really known much about.”

After graduation, Jewell left her radio days behind as she pursued her career as a historian. But when Vanderbilt sold WRVU’s FM license to Nashville Public Radio in 2011 and the student-run station became an internet-only stream, she saw it as a signal that an important era was coming to a close — not just for Vanderbilt but for college radio as a whole.

The result is “Live from the Underground,” which examines how college radio stations all over the United States came to have such an outsized impact on the culture and politics of those decades. Delving deep into the archives of dozens of stations from Cambridge to California, Jewell highlights the role these institutions played in elevating boundary-pushing, out-of-the-mainstream music and cultural perspectives in their communities.

According to Jewell, the status college radio attained in that era was largely an accident — a strange, unexpected confluence of progressive New Deal-era public policy and a subsequent neoliberal shift in broadcast regulations that ended up backfiring on its corporate proponents.

“The noncommercial identity of college radio is shaped by this idea of ‘educational radio,’ which was developed by reformers from the 1930s who were trying to carve out a space for content that wouldn’t have a broad, commercial appeal,” said Jewell. “Their hope was to use radio to knit communities together and speak to the nation’s cultural pluralism.”

But in the 1970s, a conflict arose between professional public radio and the more amateurish college radio, whose tiny, 10-watt transmitters often clashed with the signals of larger, more polished NPR affiliates in their broadcast areas. In 1978, lobbying from those bigger stations led the FCC to eliminate the Class D licenses that many small college stations relied on in an attempt to push them off the air and free up broadcast bandwidth.

“Ironically, a lot of those small, 10-watt stations actually upgraded their signals” in order to keep broadcasting, Jewell said. “Suddenly, these stations that were invested in cultural exploration and speaking for communities that weren’t being served by commercial radio become more visible. And eventually, the music industry started to incorporate those signals into their business model.”

This increased visibility happened to coincide with the emergence of the punk, post-punk and new wave, largely youth-driven genres that espoused a countercultural ethos. As a result, college radio stations like MIT’s WMBR, Emerson College’s WERS and Boston College’s WZBC became a way for offbeat artists and independent record labels, who struggled to find a home in the mainstream, to reach a wider (though not necessarily a mass) audience. “The policy changes created the space for this artistic movement to gain purchase on the airwaves,” said Jewell.

While histories of American punk rock rightly center New York City as its birthplace, Jewell makes the case that it was Boston college radio that helped nurture it into the cultural force it became. “The key place is MIT’s radio station, which had a lot of community DJs who were connected to the punk underground,” says Jewell. “And they claim the status of having the first punk rock radio show. They were really embedded in that scene and were committed to bringing that music onto the airwaves.” Boston’s status as a major college town meant that these DJs could reach students and young people who’d come to the city from all over the country and very likely would bring this new music back to their local scenes, where it may otherwise have gone unheard.

“Live from the Underground” also shows how college radio stations were often riven and driven by internal tensions over what they should be: Power struggles between students who saw the stations primarily as a means of professional development and those who viewed it as a vital medium for cultural or artistic expression; fights between stations and university administrators over profanity, censorship and the artistic merit of the content being aired; and arguments between staff, who saw stations as a refuge from the homogeneity of campus life and the broader student body, which often couldn’t understand why their school’s radio station wouldn’t just play normal music that everybody liked. These conflicts helped define what college radio would become, and acted as a crucible for students who participated, helping shape their attitudes, their values and their careers.

“I think of [Public Enemy frontman] Chuck D at Adelphi University as the best example of this,” Jewell said. “He saw the radio station as the place where he found his voice. It helped him figure out who he was as an artist and how he was going to project himself.”

In the present, however, many of the things college radio stood for in the indie/alternative era have less salience than they once did. The internet has fractured the once dominant monoculture that spurred many student DJs to combat ubiquitous corporate schlock by championing lesser-known artists. New avenues for discovery, such as streaming services or social media, have made finding new music easier than ever (though they aren’t without their flaws).

Jewell is particularly disappointed when universities such as Vanderbilt abandon their broadcast signals because, to her, it means that they are retreating from the public square and have given up on the mission of connecting to the communities around them. “College radio’s function still exists,” Jewell said, “so long as universities continue to see that there is a benefit in maintaining these signals as a place that can reach out to the larger community.”