Advertisement

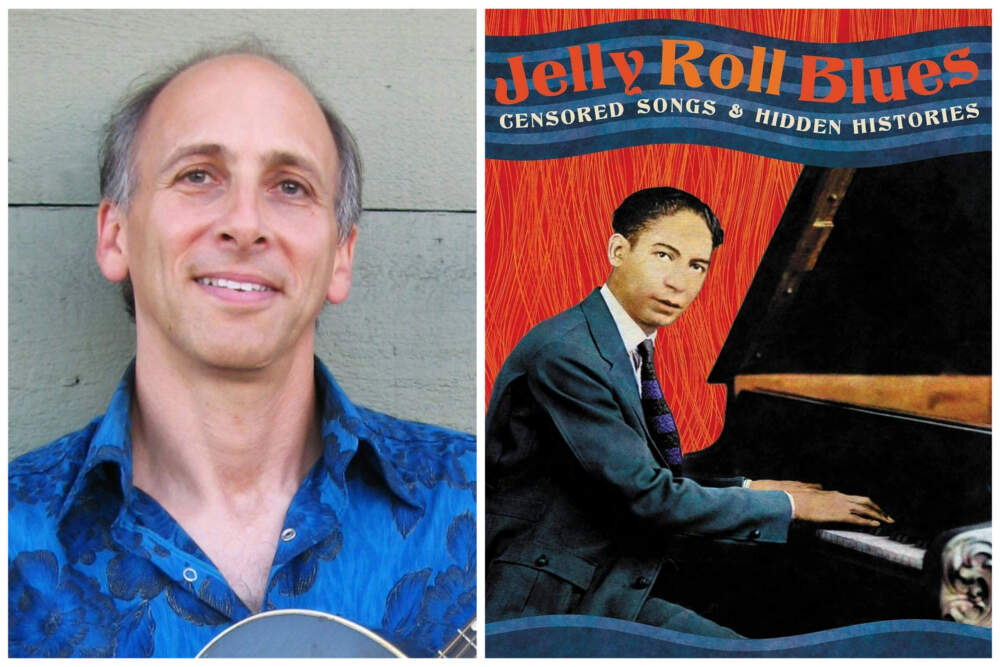

Elijah Wald uncovers the censored world of early jazz in 'Jelly Roll Blues'

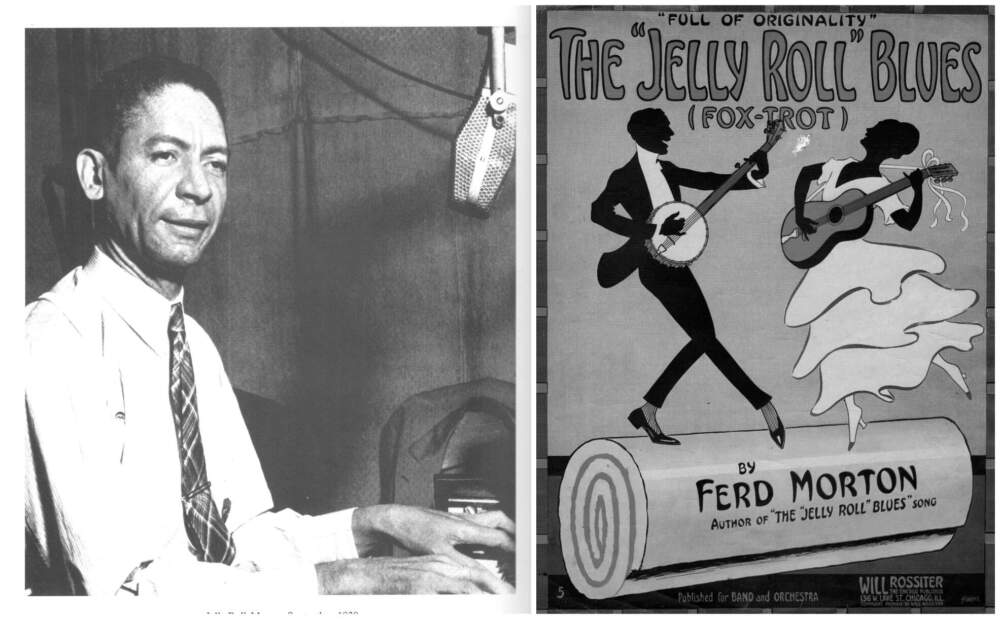

In 2005, fans and scholars of early jazz and blues were handed the keys to a buried treasure chest: an eight-CD set of recordings that New Orleans pianist Jelly Roll Morton had made at the Library of Congress with folklorist Alan Lomax in 1938. The interviews and performances included not just the songs that made Morton a key figure in American music, but also a collection of highly explicit ditties that Morton said came from brothels where early jazz artists played for sex workers and their clients, as well as a shocking 30-minute, expletive-laden tale of sex and violence called “The Murder Ballad.”

When the recordings came out, Cambridge-born author and musician Elijah Wald was doing academic work on Chicano hip-hop. “I had a class full of kids who were listening to Lil Jon, and their parents were saying ‘No one sang anything like this back in our day,’” laughs Wald. “I was struck by the similarity of a lot of the lyrics that [Morton] was doing from 1907 or thereabouts to the gangster rap I was hearing.”

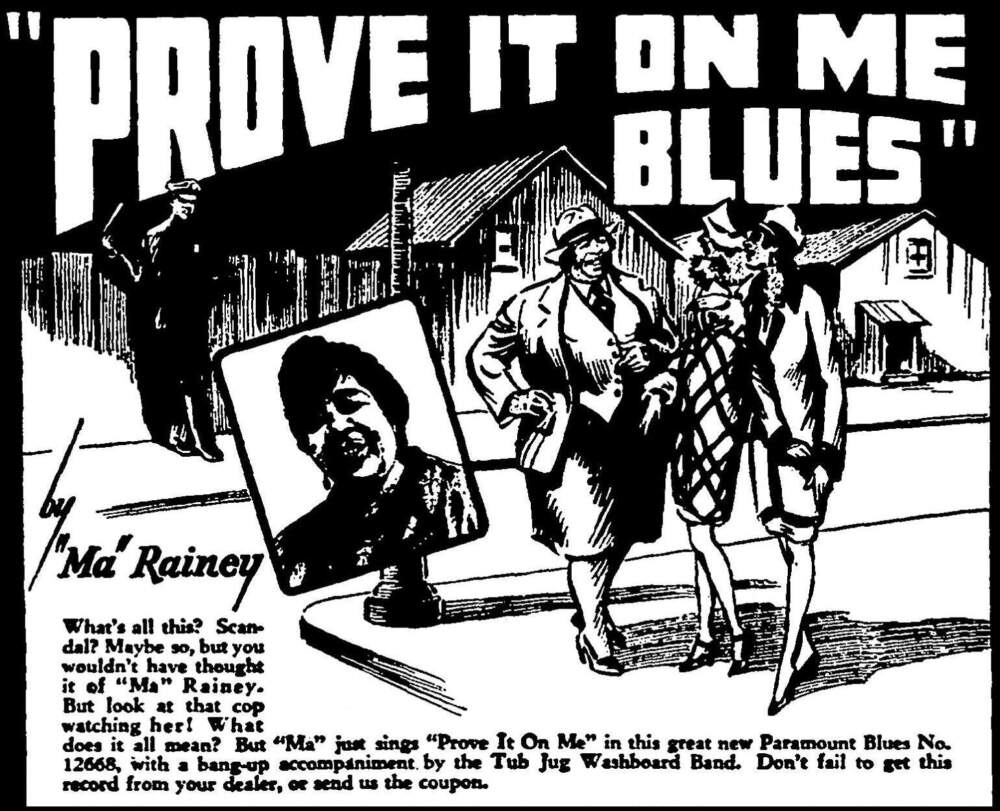

Wald’s research into how the “sporting world” of early 20th-century red-light districts and Black sex workers helped shape American music resulted in his new book “Jelly Roll Blues: Censored Songs and Hidden Histories.” The book examines how ribald rhymes heard in fields, jails and queer-friendly underground parties were buried for decades by folklorists and record companies who were either uninterested or simply not allowed to collect and issue such material.

In many cases, self-censorship as much as government codes resulted in the material being neglected by music histories. Wald found that folklorists kept binders of explicit material they couldn’t publish.

“Particularly when you're dealing with a world where a lot of the material is from Black working-class women, and the people who are writing about it are middle-class white men, there are these layers — ‘maybe I shouldn't be telling him that,’” observes Wald.

In the book, Wald goes beyond the musicians who recorded and tries to bring out the perspectives of the audiences they were singing to. “A lot of this project was about trying to find Black voices from this period with fewer filters than we normally have,” says Wald. Many of those voices were from people who had been interviewed by Robert McKinney, a Black New Orleans journalist who was employed by the Works Progress Administration in the late 1930s. McKinney kept a private file of bawdy rhymes told to him by bar patrons and dock workers. Wald is hoping that a future book will fully anthologize the writing of McKinney and the world he captured.

Cities like New Orleans and Chicago had such vibrant red-light districts that visitors could pick up Blue Book directories, which listed sex workers and bordellos, as well as businesses that thrived in such districts like pharmacies, liquor supplies and lawyers. Wald says he discovered through his research that piano players in brothels were often hired so that patrons would stay after going upstairs and spend money on liquor.

Advertisement

“It’s the audience, not the artists, that supplies the scene, and in the case of early blues, I began to notice that when musicians like Jelly Roll Morton and Louis Armstrong talked about blues, they were talking about it as the music they would play for the women early in the morning, after the houses had closed down,” says Wald.

Noting the prevalence of lesbianism themes in early blues, Wald explains that “they don't want to hear about sex with men. That's work. But the other thing that was striking at that point is realizing how many of the songs about sex work are about the work, not the sex.”

While they would never have made it onto the radio, the songs Morton played for Lomax often had deep roots in oral traditions and went well beyond the South. One, “The Winding Ball,” seems to have been a descendant of a folk song collected by Scottish poet Robert Burns. Wald discovered that in 1934 the Bangor Daily News printed, upon a reader’s request, a few verses as remembered by a Maine logger. A blues song about sexual fluidity reminded Wald of a ditty his father, a Nobel prize-winning biochemist and Harvard professor, had sung.

Censorship has continued to impact music history in more recent decades, points out Bernard “Smok N Strok” Johnson Jr., a Boston hip-hop artist with the Hangaz and a contributor to the Massachusetts Hip-Hop Archives. Johnson notes that hip-hop albums have long carried parental advisory labels, and he remembers being confused at why lyrics were missing from songs when he would hear the so-called “radio edit.” “I truly didn’t understand what was going on,” he says.

Johnson says hip-hop lyrics and themes became especially scrutinized after white artists like Eminem rose in popularity. “Before, it was a culture that mainstream white America didn’t care about, but now there’s an eye on it, about who is saying what.”

While blues may no longer be linked to sex work the way it once was, artists who sing it still have to consider how far they can go. At book events, like the one happening April 29 at Harvard Book Store, Wald is bringing his guitar and playing some of the censored songs he writes about. He admits that he was initially reluctant to sing songs that are “dirty and funny” in public, but that audiences “want the R-rated presentation. So I’m learning to do what Jelly Roll Morton would have done: read the audience.”