Advertisement

The heyday of local disco remembered in 'The Boston Hustle'

Fifty years ago, a streetwise East Boston tough kid named Joey Carvello, tossed out of the Army for selling drugs, chose a new destination for one of his frequent nights out on the town. He and his pals, bathed in English Leather cologne, ended up at Zelda’s, a hot spot located on the stretch of Commonwealth Avenue in Brighton that now houses a Herb Chambers auto dealership.

Carvello was used to “bucket of blood” joints with 25-cent beers, brawls, goldfish-eating contests and a live band. Instead, he found a line of impeccably dressed patrons hoping to get in — bribing the doorman helped — and inside he saw a parade of astounding dance moves. And while Carvello had spun records himself, on this night, he witnessed something new: A DJ who could seamlessly blend and remix funky discs to create a nonstop soundtrack for the dance floor.

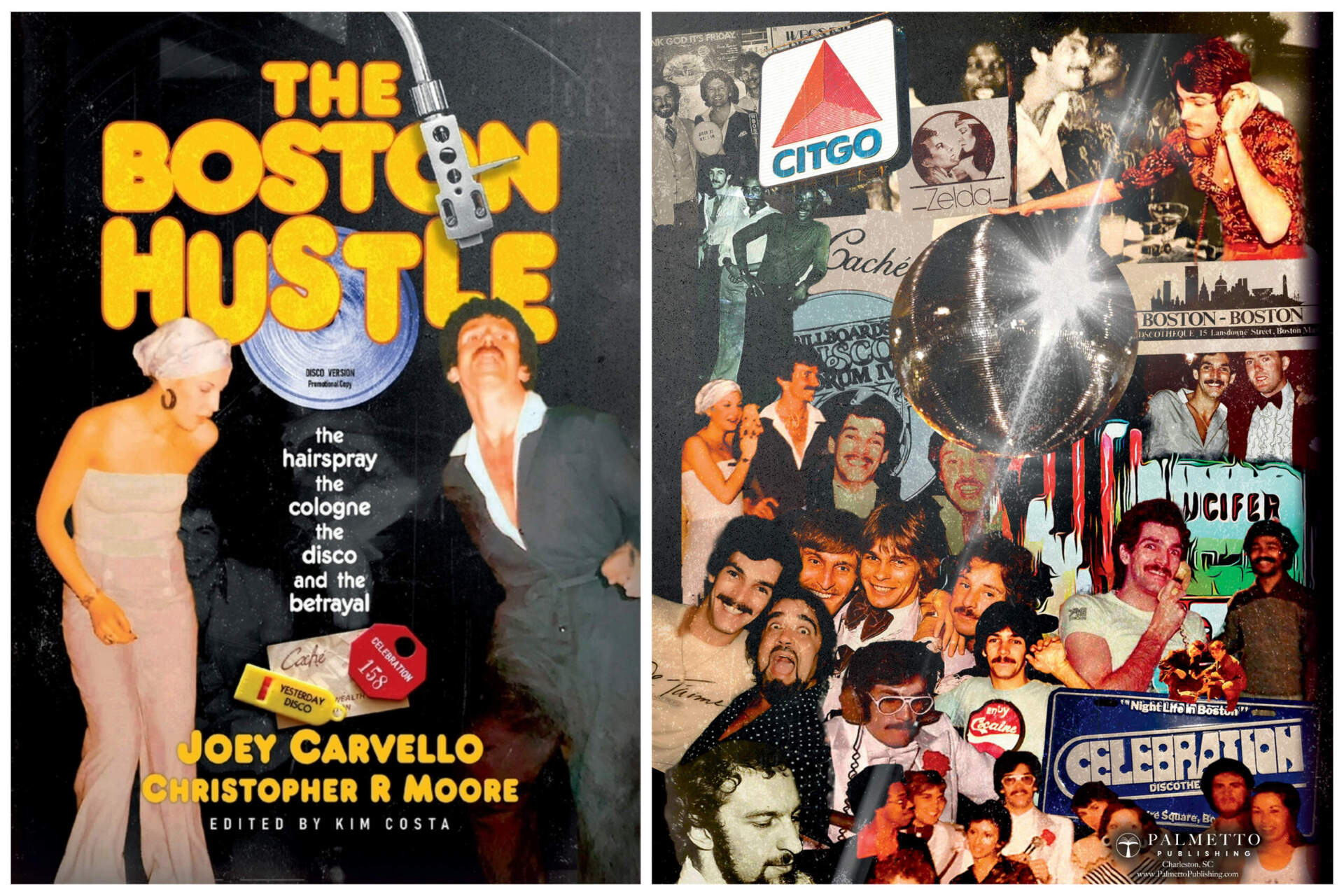

Soon Carvello himself would be the one in the DJ booth, playing at seminal Kenmore Square discotheques Yesterdays and Celebrations. Now those heady, cocaine and Quaalude-fueled nights are captured in Carvello’s memoir “The Boston Hustle: The Hairspray, the Cologne, the Disco and the Betrayal” (co-written with Christopher Moore), a tale about how disco ruled the city in the years before “Saturday Night Fever” and the disco backlash.

While most disco histories focus on the New York club scene, Carvello, now a New Yorker himself, says Boston played a key role in dance music history.

“New York had gay, Black, Hispanic and some quiet, mobbed-up Italian American spots,” he says. “In Boston we were a melting pot. RCA Records would come to Boston before they went to New York to break records. When Billboard and Record World Magazine had disco reports, they were watching Boston because we were so progressive.”

New England wasn’t just the home of disco superstars Donna Summer and Tavares. Carvello says that much of Boston’s influence on the disco charts came from the 1975 founding of the Boston Record Pool by his mentor John “TC” Luongo. The two met after the famed Charlestown R&B collector known as Eddie B. told Carvello to go see Luongo spin at The Rhinoceros Club, a downtown spot that catered to a Black audience. Before Carvello dropped Luongo’s name, the doorman implied that a white patron might want to go elsewhere.

Advertisement

The record pool sent out new music to DJs who would then rate the songs after seeing how clubgoers responded. “It united all the DJs — gay, straight, and Black — and that solidarity meant we could break new music here.”

Boston’s dance music venues initially reflected the segregation of 1970s Boston. When Carvello’s Thursday night residency at Yesterdays began, he recounted how the club’s management made sure that Black people rarely got past the doorman, even though the music being played was mostly by Black artists. Carvello ended up quitting over the admission policy, and after the club saw a massive drop in revenue he was reinstated and allowed to play to an integrated room.

Carvello says that the famous velvet ropes at Studio 54 were about “keeping people out of clubs, being elitist.” In contrast, he says that Boston’s early discotheques “had blue collar guys who at night turned into dancers and players. Then they would go home, go to their 9-to-5 job, have dinner, take a nap, and go back to the club.”

There were also plenty of underworld figures, and in “The Boston Hustle” the drug use of Carvello and his friends is recounted with the same detail he gives to the colognes and polyester outfits.

“The drugs were fantastic,” he says unapologetically when asked about that aspect of the culture. “It was part of our lifestyle. The cocaine wasn’t cut, so there was no hangover.”

On his nights off, Carvello also checked out what his fellow DJs Jimmy Stuard and Danae Jacovidis were playing at the Back Bay clubs like Chaps, Styx and 1240 that were part of Boston’s then-vibrant gay club scene. “Jimmy had gone to MIT for engineering — he was an absolute master of the blend,” recalls Carvello.

“The Boston Hustle” isn’t just a richly detailed and often shockingly uncensored tale of ungentrified Boston. It’s also a look at the music’s death. Carvello says after “Saturday Night Fever” came out near the end of 1977 the scene became oversaturated, with so many discos popping up that it seemed like “every Chinese restaurant turned into a disco at 10 p.m.”

And while Carvello was proud of how his generation of Italian Americans were integral players in disco culture — “Fly Robin Fly” by Silver Convention was a favorite with that crowd — he knew the end was near when “my uncle came to the club with his orange jumpsuit and comb over hairdo.”

More nefariously, Carvello writes that the same record labels that hit paydirt with disco literally helped burn it down by aiding Chicago DJ Steve Dahl’s infamous Disco Demolition stunt. Carvello adds that while disco was profitable for labels, the employees tasked with promotion often resented how disco outsold other genres.

“This was the first time Black artists had an unfettered lane to promote their music,” he says. “They could move out of small Black clubs into the mainstream… But there were people who hated that they had to promote this music that was Black and gay. I was there, and that’s why I wrote this book.”

As new wave and house music came, Carvello’s DJ sets changed with the times, and — like several of his 1970s Boston peers he went on to a lengthy career in the music industry. He still DJs from vinyl, and in an era where dance clubs are focused on selling expensive bottles, he still thinks there’s a place for venues that cater to regular people who want to show off their dance moves when the workday is done.