Advertisement

Review

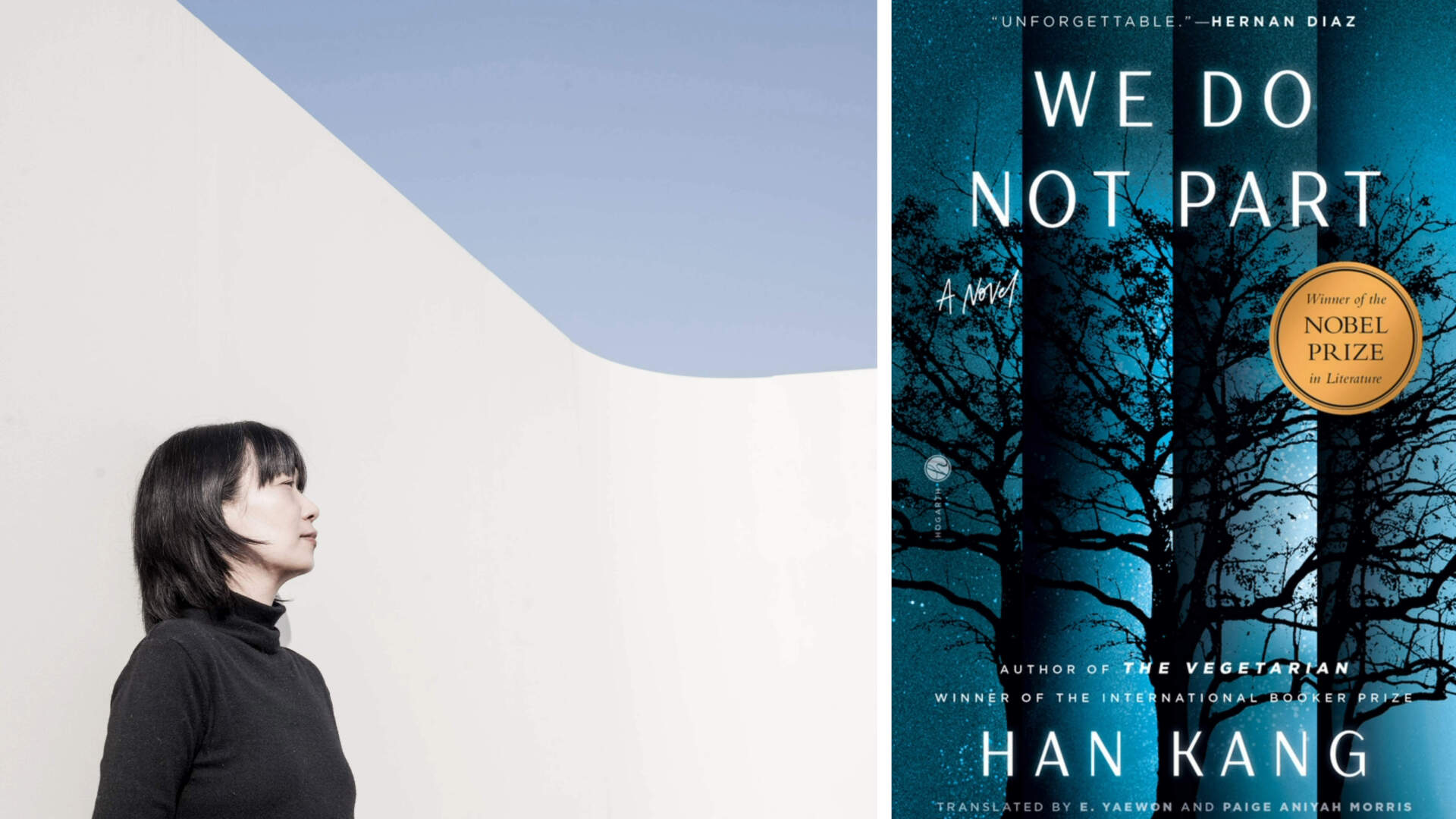

Han Kang's 'We Do Not Part' counters unimaginable brutality with courage and empathy

Last year, novelist Han Kang became the first Korean writer to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. In her banquet speech, she posed some questions that, as she stated, “have been asked by literature for thousands of years.” One of these: “How difficult is it for us to remain human, come what may?”

Han has addressed this question often in her writing, notably in her 2017 novel “Human Acts.” She does so again, in ways haunting and beautiful, in her fifth novel, “We Do Not Part.” This is a work of fiction in which unimaginable brutality, based on real-life events, is countered in great part by actions of profound courage and empathy.

Set mostly in present day, “We Do Not Part” highlights the generational trauma that flows through one family from the massacre on Jeju Island off the coast of South Korea, whose waves of brutal killings began in 1948. In the name of stopping the “communization” of Jeju, at least 30,000 people, including 1,500 children, were killed by authorities and by extreme-right militant groups. The actual numbers are unknown; news of the event was suppressed by the government for decades.

Han’s works, which are resonant with conscience and revealed history, have been translated into more than 20 languages, and have received numerous awards, including the 2016 International Booker Prize for “The Vegetarian,” a novel that is also included in The New York Times “100 Best Books of the 21st Century.”

American readers were initially introduced to Han’s writing in the literary journal of the Harvard University Korea Institute, “Azalea: Journal of Korean Literature & Culture.” Its 2010 issue included an English translation excerpt of “The Vegetarian” six years before the novel’s 2016 U.S. edition.

Signaling that “We Do Not Part” may require more than one dimension to fully tell its story, it opens with the protagonist, Kyungha, waking from a nightmare she has had before. It is so real that she considers the idea that “with some dreams, you awake and sense that the dream is ongoing elsewhere.”

A journalist, Kyungha has written a book about a massacre that took place in a city only identified as “G–.” We learn glancing details about her: her work may have ruined her marriage; she has spent recent months alone in an apartment in Seoul, barely eating, beset by migraines; she spends most of her waking hours obsessively writing and rewriting a will.

When Kyungha does finally venture out, some activities on the streets seem unreal; her nightmares have so merged with her waking hours that she doubts her own perceptions. From the novel’s beginning, there is a sense that much more is happening beyond what can currently be seen or heard.

Advertisement

And then Kyungha receives an unusual request from her friend Inseon, who is in a Seoul hospital after a horrific accident. Could Kyungha travel to Inseon’s home (in a remote village on Jeju Island) to feed her pet bird? Inseon had been airlifted out so quickly she is worried her pet will die.

Though very different personalities, the women have been close for almost two decades. Inseon, a documentary filmmaker, is assured and outgoing; Kyungha more introverted. They’ve spent their careers bringing lost lives to light; as Kyungha always remembers of her research, “the blood running beneath the numbers.”

Kyungha lands on Jeju in a raging blizzard that has reduced the world to snow and wind.

Throughout the novel, Han uses snow as a narrative frame and a nearly otherworldly presence, in turns majestic and ominous. It can expose or obscure the footprints of those who have fled into hiding; it can absorb the sound of voices and breath. Snowflakes can lie, unmelted, on the lifeless faces of the fallen.

After a treacherous bus ride and even more treacherous hike, Kyungha arrives at Inseon’s home. The bird at first appears dead and then seems to be alive. Much of “We Do Not Part” involves a duality of seeing, and of learning to exist with the unknown.

Even with the relentless snow, Inseon soon arrives, which would seem impossible given her injuries. But to Kyungha, she is quite present, getting items from cupboards and firing up the stove and, most importantly, sharing her family story of the Jeju massacre.

Inseon had grown up amid the aftershocks from these events, but never with an explanation of them. The few who survived, like her mother, “never talked about what happened.” Only toward the end of her mother’s life did Inseon learn that she had led a group that pressured authorities to disclose truths about the Jeju massacre and a related massacre on the mainland. How it took decades to gain answers.

Han tells the mother’s story in the character’s first-person voice. Phrases are planed down to their essence, the better to carry the weight of the horrors endured and the many departed she mourned. How in village after village, residents were rounded up and butchered “in a nearby field or by the water” and then their houses burned. How she searched for years for her brother, on the slim rumor that he had also escaped.

During the snowstorm, regular actions between the two friends, like making tea and talking as they usually do, amplify the dreamlike, between-worlds atmosphere.

Is Inseon actually on Jeju or is she a fever image? Is Kyungha alive or now a spirit? Han’s masterful storytelling makes the enigmatic aspects feel spellbinding more than confusing, large enough to encompass how, even when met with crushing circumstances, the basic human bonds — between friends, within families, among the living and the lost — can hold.

In a 2017 New York Times opinion piece, Han noted that in war there is a “critical point” when “human beings perceive certain other human beings as ‘subhuman.’” The “last line of defense” against this, Han posits, “is the complete and true perception of another’s suffering.”

As a bulwark against the loss of humanity, “We Do Not Part” is a best defense.