Advertisement

Review

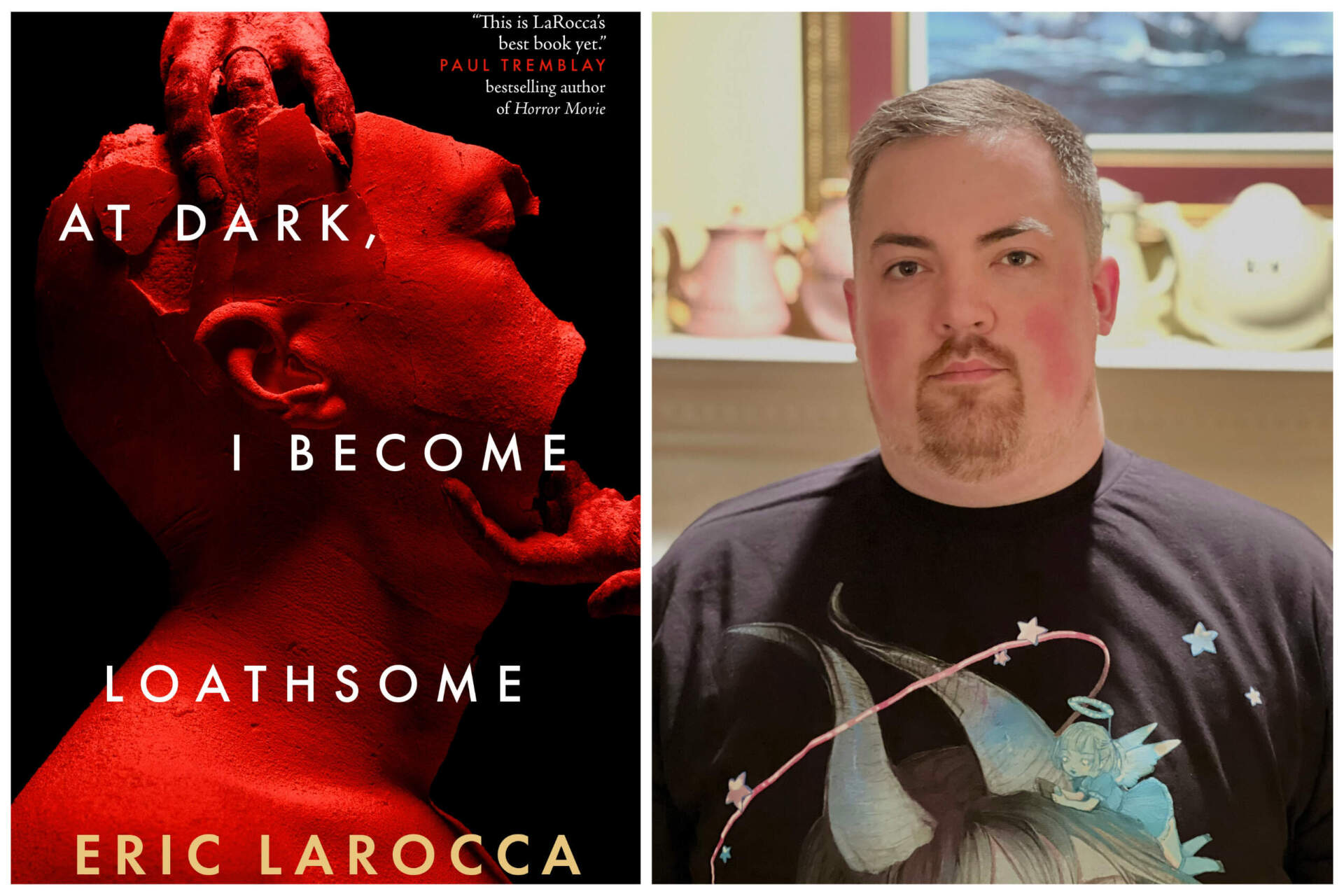

Boston author Eric LaRocca's latest novel delves into the horror of grief

Transgressive fiction has a rich and controversial history in literature, from the antique obscenities of Comte de Lautréamont and the Marquis de Sade to the gruesome fantasies of more modern authors, such as J. G. Ballard, Bret Easton Ellis and even Stephen King. Perverse sexuality, unflinching violence and inverted moralities are the hallmarks of the genre, practiced by prurient protagonists who revel in their cruelty and challenge readers to consider whether the guilty pleasure they feel when reading such horrors hints at something darker within themselves. The purpose is to shock; the hope — when there is some intention beyond mere gratuitousness — is that by exploring the extremities of experience, some deeper truth might be revealed or some moral hypocrisy may be shattered.

It doesn’t always work out that way, though.

Boston author Eric LaRocca has been lauded as a bright light in horror fiction, particularly its “splatterpunk” subgenre, marked by its emphasis on gore and violence. In 2023, Esquire magazine named them as one of the writers at the forefront of the “next golden age of horror fiction,” citing their blend of queer themes, online tropes and unrelenting extremity.

Their latest book, “At Dark, I Become Loathsome,” is squarely in line with that description, telling the story of Ashley Lutin, a man whose grief over the loss of his wife and son, and struggle with accepting his own sexuality, have sent him into a deep, nihilistic depression. He’s become a kind of immersion therapist for immiserated people, burying them alive for 30 minutes at a time to provide them with a new perspective on life. But when a potential client captures his attention with a gruesome story, something dark is awakened in Ashley, and he begins down a path that threatens to lead him somewhere from which there’s no coming back.

In total, “At Dark, I Become Loathsome” feels more like three short stories in a soiled trench coat than a proper novel. Though Ashley’s story provides a modicum of structure, it’s interrupted by two extended digressions. The first, which we can call Keane’s story, is a tale of illicit sex and murder, told to Ashley via an online chat by his mysterious potential client. The second, which Ashley reads on a blog, is titled “The Ordeal of Victor and Tandy” and recounts a man’s paraphilic fetish for his partner’s cancer.

These stories, which are only incidentally related to Ashley’s descent into darkness, take up a large part of this already slim volume. Moreover, these stories are perhaps a little too true to their supposed media — they really do read like the kind of thing someone would DM you or that you would read on a random person’s blog — meandering and rough, in need of a little more thought and editing. LaRocca presents Keane’s story in chatroom format, without indentation and with each new sentence prepended by the client’s username, “<masterjinx76>.” Points for verisimilitude, I suppose, but not easy to slog through as a reader.

Ashley is a peculiar character. The book’s title is a kind of mantra for him, something he repeats while reflecting on the abased state he finds himself in. As a reader, however, it’s not clear that he’s particularly loathsome at night, or any less so during the day. This is of a piece with Ashley’s general perspective — he’s convinced that the world sees him as a monster, but you get the feeling that it’s mostly all in his head, a symptom of his own self-loathing (and, potentially, his narcissism).

The net effect of this, though, is that he comes off a little goofy. It doesn’t help that his screen name is “<sad_boy>.” “I’m sure that some of my clients expect me to behave a certain way,” he muses, “given the outlandishness of my appearance — the large, bee-stung lips, my forehead with its silver horn implants, my jewelry-decorated ears, bent and reshaped to resemble the ears of an elf.” A middle-aged man, he stalks around his small, Connecticut town brooding like a teenager who just discovered Hot Topic and Nine Inch Nails.

It appears that LaRocca wants us to see Ashley as a thoughtful, erudite, philosophical character, but the dense, overwrought way in which he speaks makes it seem like the only book he’s ever read is a thesaurus. If we were viewing him in the third person, there might be an air of mystery and intrigue surrounding his dark dealings. But in the first person, with full access to his thoughts and motivations, Ashley is mostly just irritating. “I think of the blood they found,” he says. “I imagine it pulsing beneath me like a gentle current, carrying me off toward a godless infinity where starlight is eaten by the fanged monstrosities we build inside our minds.”

For all the book’s pretensions to transgression — and it is filled with plenty of gross, violent and sexually explicit scenes — “At Dark, I Become Loathsome” never really reads like much more than boilerplate erotica, something you might’ve seen a decade or so ago on someone’s LiveJournal or Tumblr page. Though LaRocca is familiar with the vocabulary of transgression, they seem not to grasp its grammar, failing to employ their vivid grotesqueries into something meaningful or coherent. What’s left is a story about grief and loss that seems to misunderstand the very nature of those things, packed with grim imagery that I’d hesitate to call gratuitous, only because that might imply there’s something remarkable about it.