Advertisement

A rare silent film with an all-Black cast screens at the Somerville Theatre

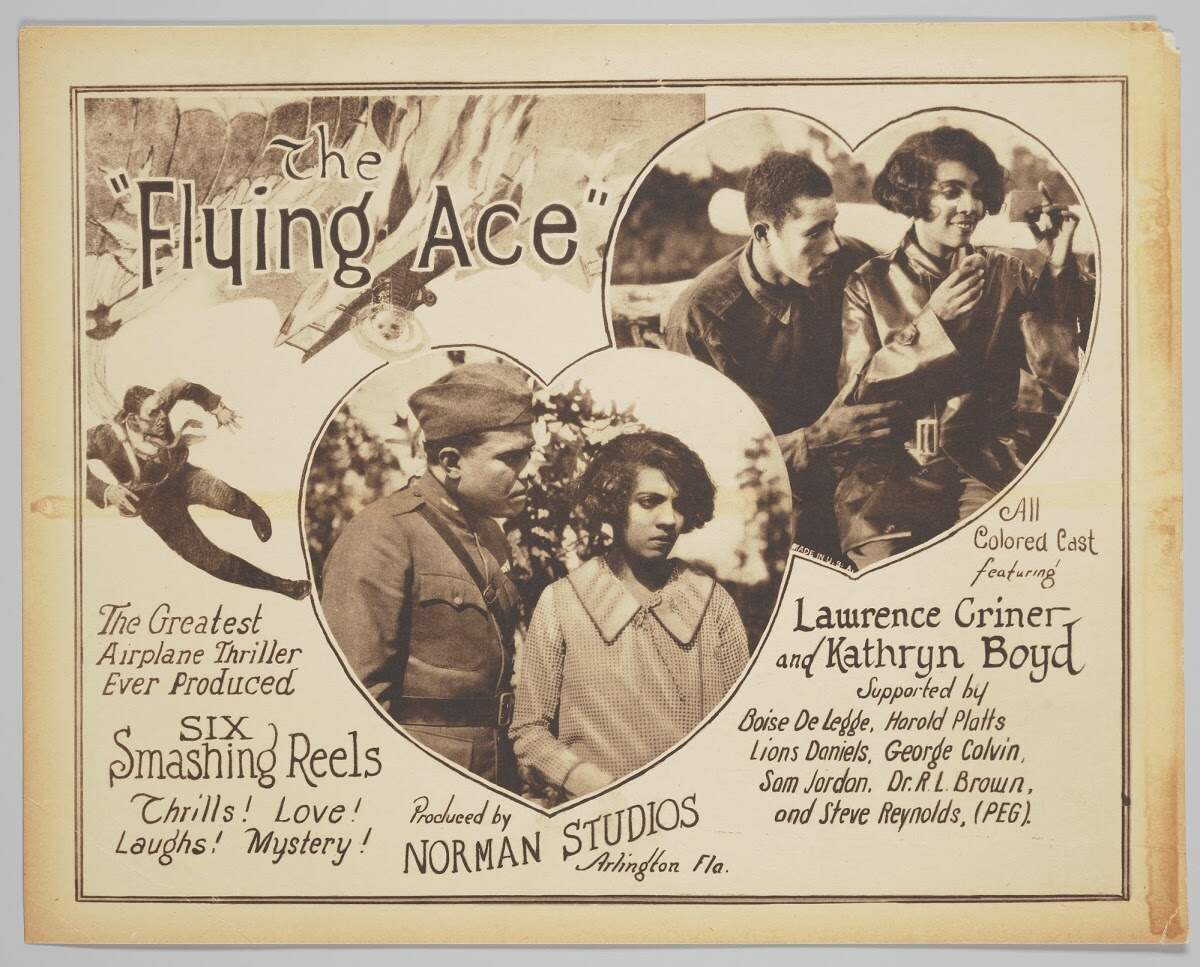

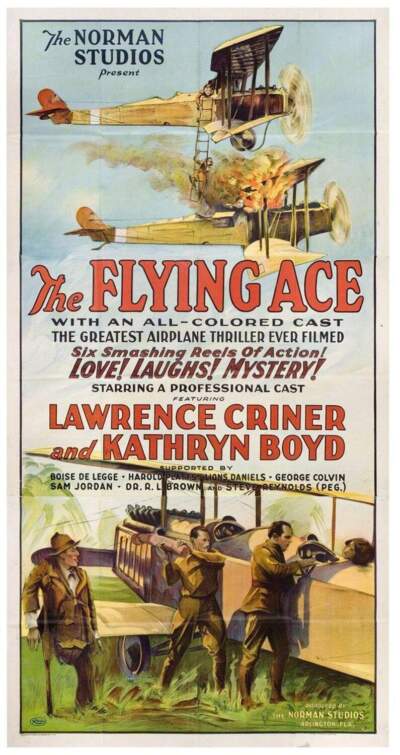

A death-defying rescue; a robbery involving trains; a love triangle: the 1926 silent film “The Flying Ace” employs some of the most durable tropes in cinematic history. But it’s got something that was rare back then and remains so: an all-Black cast.

“The Flying Ace” will be screened with live musical accompaniment at the Somerville Theatre on Feb. 2 in honor of Black History Month. The film, which was named to the U.S. National film Registry in 2021, is one of the few remaining examples of a genre of early cinema marketed to Black audiences during the era of segregation. Race films, as they were called, featured Black actors and offered an alternative to mainstream Hollywood depictions of race, where white actors in blackface were par for the course.

“This was a moment when mainstream film was consolidating around stars, around genre filmmaking and around forms of spectacle,” said Allyson Nadia Field, a professor of cinema at the University of Chicago. “All of which race films were trying to emulate, while centering Black subjects and stories.”

“The Flying Ace” concerns the disappearance of a large sum of money from a railway station. Investigating the case is Captain Billy Stokes, a World War I fighter pilot and war hero who returns to his old job as a railroad detective and is played with quiet authority by the popular stage and screen actor Laurence Criner. In the midst of many life-threatening escapades, he courts the station master’s daughter, Ruth Sawtelle, a charismatic Kathryn Boyd.

Criner and Boyd were a real-life couple, which would have been part of the appeal to audiences who were already showing an interest in the lives of film stars. The aviation theme was a draw, too. Boyd’s character was modeled on Bessie Coleman, the first female African American pilot. Coleman was in talks to play the part of Ruth, but died in a plane crash in the spring of 1926. Ruth appears in the film in a belted jacket and an aviator hat, an homage to the aviatrix who inspired her.

But perhaps most notable about “The Flying Ace” is its absence of racism – or, for that matter, any white people. Black actors play every part in the movie, from the station master to the pilot to the criminal he apprehends. The character of Stokes is aspirational, too, as African American soldiers were not allowed to serve as fighter pilots until 1941.

“ It's a fictional narrative, but it has references to real world heroism of Black veterans in World War I,” Field explained. “[It] is creating a hero that really responds to audience desires, offering a role model that's absent in Hollywood films.”

This mode of Black cinematic storytelling was not the only approach filmmakers took at the time. Some chose to deal directly with racism, refuting the damaging and violent beliefs promoted by films like “Birth of a Nation.” There were examples, too, of race filmmakers relying on tropes and caricatures that Black audiences found offensive.

“ People were, I think, mixed,” said Charlene Regester, a professor of African American studies at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “On one hand, they were excited to see Blacks on the screen, yet at the same time, they realized that they were being caricatured in particular ways, and I imagine that they would have resented that.”

Race films were produced by both white and Black filmmakers, perhaps the most famous of whom was the prolific African American director Oscar Micheaux. “The Flying Ace” was made by the white filmmaker Richard Edward Norman in Jacksonville, Florida, where a motion picture industry thrived at the time. Many such films were made on shoestring budgets, and “The Flying Ace” appears to be no different; the movie's airplane, clearly a mock-up, is only ever pictured on the ground.

Advertisement

That scrappiness makes it all the more remarkable that “The Flying Ace” survived.

“We have a sense of what American film history is based on the survivors, and those survivors are skewed towards the very well capitalized film companies, the ones that were copyrighted and therefore saved at the Library of Congress,” Field said. “When in fact, American film history is so much more diverse, far more representative of the nation, than the survivors account for.”

Many of those survivors depict shocking racial caricatures that modern audiences will likely find as objectionable as Black moviegoers did when the films were first released. In this way, “The Flying Ace” offered a rebuttal to the time's mainstream cinematic sensibilities, and expands the modern understanding of what early cinema was.

“ When you see these films projected, you get a sense of what was so valuable about race films,” Field said. “The impact of scale, seeing these faces and figures given the star treatment that Hollywood denied them.”

"The Flying Ace" (1926) will be screened Feb. 2 at 2 p.m. at the Somerville Theatre, 55 Davis Square, Somerville. The screening will feature live music by silent film accompanist Jeff Rapsis.