Advertisement

John Wilson's portraits at the MFA blaze with humanity

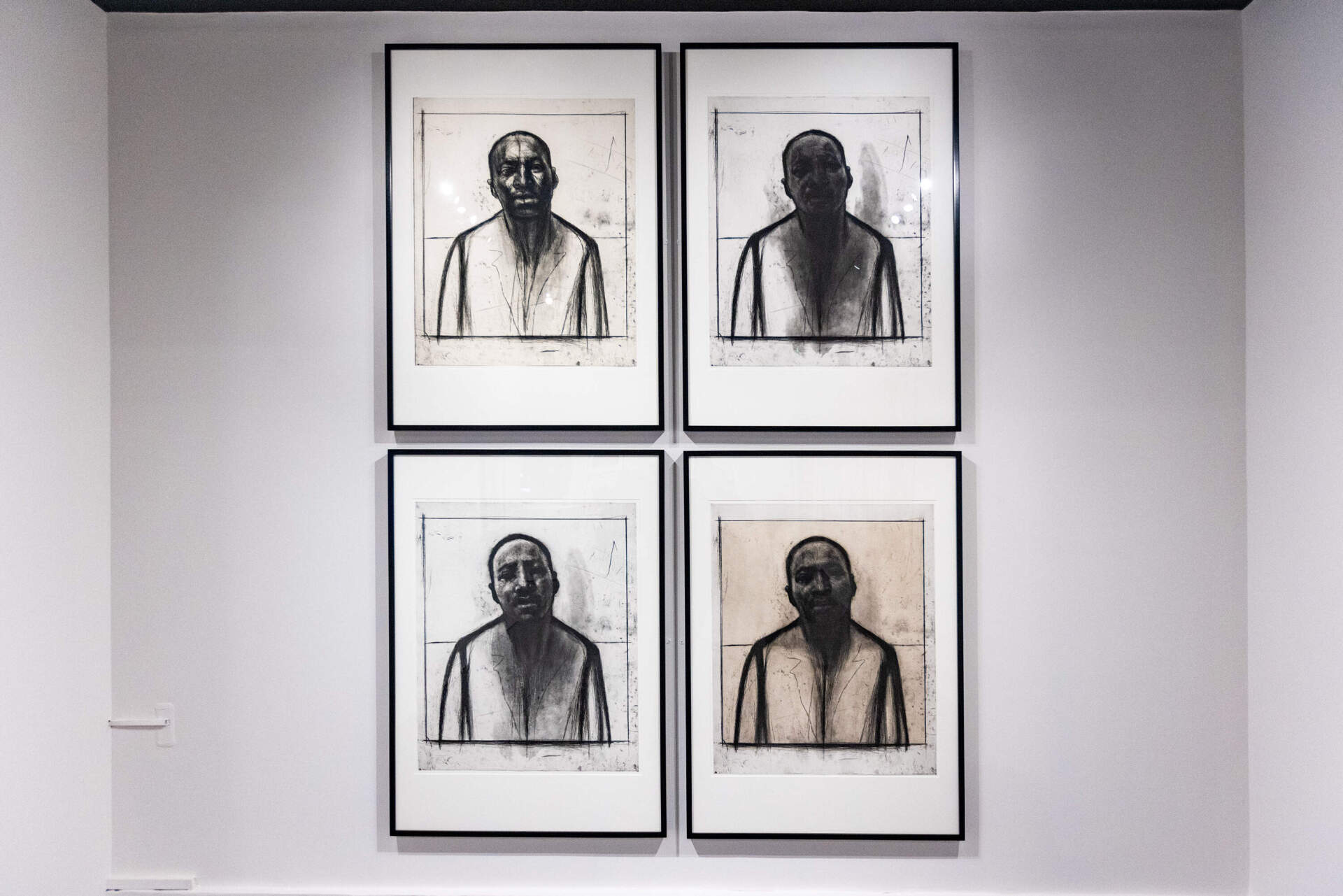

Roxbury artist John Wilson spent his decades-long career creating drawings, paintings and sculptures that explored what it meant to be human. Born in 1922 to Guyanese immigrants, his work was deeply informed by his experience being a Black man in twentieth-century America.

More than 100 of his works are the subject of “Witnessing Humanity: The Art of John Wilson,” a new exhibition on view through June 22 at the Museum of Fine Arts. “Wilson described what he wanted to achieve in his work was to create what he called 'powerful images' that would force others to see what he saw,” said Edward Saywell, one of the curators of the exhibit. “He wanted to force others to experience what he was experiencing growing up in Roxbury.”

Wilson wrote in notes for a lecture at Tufts University that he was often exposed to images that depicted Black people “as dehumanized caricatures.” A graduate of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and a global traveler, Wilson was also keenly aware of the absence of Black artists and Black bodies as autonomous subjects in major museums.

“Many artists of that generation were being swayed towards the dominance of abstraction,” said Edmund Barry Gaither, the executive director and curator at National Center of Afro-American Artists in Roxbury. Gaither met Wilson in 1969 and remained close with him for decades. “There were many people in that time who felt that the use of figurative subject matter was old fashioned. But John remained committed to the figure as the image at the center of his work.”

This is evident in the portraits of Wilson’s wife, his children and family friends on display in “Witnessing Humanity.” Some are done in charcoal and others are rendered in vivid colors. “You see in these portraits a particular person and place and time,” Gaither pointed out. “But when you step back and look at it, you also see a universe of people.”

By recreating the scenes and people he knew, Wilson was able to connect the personal to a global conversation about race, identity and belonging, said Leslie Hammond King, another curator of “Witnessing Humanity.” “He was so acutely sensitized to what is necessary to tell a story visually that will bring people to the understanding of why portraiture is so important.”

Advertisement

Wilson extended this idea of using the figure to expand notions of humanity through his illustrations for children’s books. A display of books features different titles like “Striped Ice Cream,” “Malcolm X” and “Street Children” that helped provide positive representations of Blackness to children. One book, “Becky,” was written by Wilson’s wife, Julia. It depicts a little Black girl searching for a birthday gift with her mother. She finds a doll that looks just like her and the doll eventually comes to life.

Boston locals, like artist Ekua Holmes, were invited by the curators of the exhibit to contribute their personal experiences reading children's books that featured Wilson’s illustrations. Some of the quotes from these personal experiences are displayed with the books. “ In the U.S., books are being banned in libraries and schools,” said Saywell. “What Ekua speaks so powerfully to is how important and critical these types of images were for her growing up.”

Wilson was often not overtly political in his work but he didn’t have to be. "I don't sit down and think 'Well, I have to do a picture on Black people today,'" Wilson said in a 1995 interview with the Boston Globe. "What I'm doing... is exercising some of these conflicting kinds of messages that this racist world has given me." His depictions of the realities of being marginalized in a place like the United States and his dedication to providing figurative examples of Black life were as important as the colorful, bold and heavily political works of other Black artists of his time.

“ How do we see beauty? How do we interpret beauty?” asks Hammond. “What does beauty mean to us when [Black people] are so disparagingly portrayed in the media in the most unconscionable, toxic ways? The battle has been to constantly find ways to retrieve humanity.”

Hammond said that the “retrieval” of humanity is as important as the “witnessing” that’s included in the exhibition’s name. Wilson did more than just see the people around him for who they were; he was intentional about reclaiming that representation through his work so that others in the world could see that humanity too.

“ You hope that as people walk around 'Witnessing Humanity,' that some of the works really touch them,” said Hammond. “That they have an emotional response, meaning that they can see themselves or their children or their relationships in what he was trying to do.”

At the end of the exhibit, there is a maquette of “Eternal Presence," a sculpture that Wilson conceived in the 1970s. The full-size version was installed in 1987 on the lawn of the National Center for Afro-American Artists and has since become an important landmark in the local neighborhood. It's impossible to determine the gender of the face depicted in the sculpture, nor is there any indicator of whether it represents the past, present or future.

It was created to be a “vision of shared humanity,” said Gaither. “ The eternal is never missing from our concept of ourselves and how we go forward. Wilson especially wants that for his neighbors, friends and the Black community but he also wants it for the universe.”

Near the maquette, a video highlights members of the Roxbury community who share their personal connections to the sculpture. Some locals acknowledge that they didn’t actually know the piece’s official name and often just call it "the big head.” It's so widely known as "the big head" that the NCAAA has affectionately been dubbed "the big head museum." According to Hammond, knowing the actual name of the piece doesn’t really matter.

"‘Eternal Presence’ is a reality, but ‘big head’ is the heart of the community,” she said. “That's something that every artist longs for. If you know it, you love it, and you're prepared to take care of it, then the message has been received.”

“Witnessing Humanity” is an important moment in celebrating the life and work of John Wilson but Gaither points out Wilson has always "loomed large" in Roxbury. Through “the big head," Wilson’s work became an indelible part of the community landscape. This is vital in a place like Roxbury, which is rapidly changing due to gentrification and displacement. “Big head” silently observes the area, an omnipresent and constant reminder of the people, like Wilson, who call the area home.

" Lay hands on 'big head' and feel the synergy that has been imbued into that massive bronze sculpture," said Hammond. "Know that 'big head' is a guardian, an ancestor, a warrior spirit. And know that this is a sacred space."

"Witnessing Humanity: The Art of John Wilson” is on display at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston through June 22.

This segment aired on March 4, 2025.