Advertisement

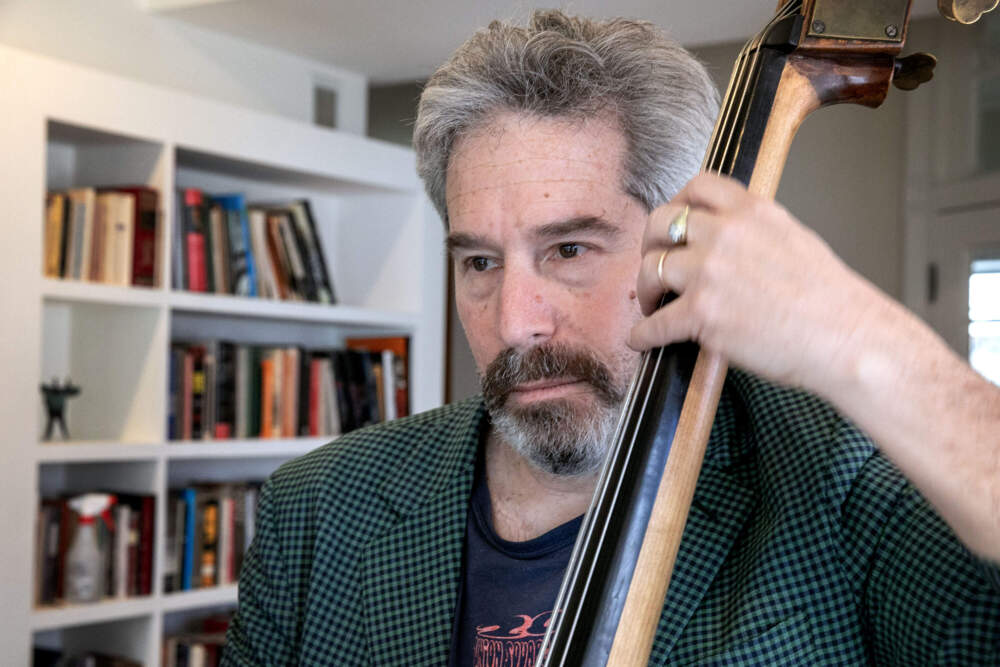

84-year-old musician Jim Kweskin returns with some new friends

In the 1960s, Jim Kweskin was famous for finding 78 RPM records of early jazz, blues and country. That collection helped fuel the sound and repertoire of the Jim Kweskin Jug Band, his influential combo that was a major attraction at Cambridge’s Club 47 and the Newport Folk Festival. The successor to Club 47, Club Passim, still displays in its tiny lobby a framed album that Kweskin recorded live at Club 47 in 1968.

These days, Kweskin is still crazy about those sounds — even if his collection now lives on his phone. “I know we’re doing an interview, but I’ve just got to play you this video of George Lewis, I think it’s one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever heard,” he says, before showing his bandmates a YouTube clip of the classic New Orleans clarinetist. Noting that as a child in the ‘50s he loved both folk music and early jazz, he points out that “when I was young this music was already old, but people are still attracted to it.”

That passion is why Kweskin, now 84, seems to be making as much music as he has in decades. The deft fingerpicking guitarist is about to release his second record in two years, “Doing Things Right,” which is credited to Jim Kweskin & The Berlin Hall Saturday Night Revue (out April 25). In a full circle moment, it’ll be celebrated with a show at Club Passim on April 8.

Berlin Hall is a reference to the Virginia function space that longtime Kweskin bassist and producer Matt Berlin’s family once ran in Newport News above their dry goods store. It hosted everything from Marcus Garvey lectures to Hanukkah parties, but mostly it had the kind of versatile bands that kept working by learning the full spectrum of early 20th-century American music. Berlin was raised in Cambridge but remembers how some vintage sounds would inspire his father to “turn around and in his Virginia accent say ‘That’s Berlin Hall stuff, boy!’ ”

That joyful versatility results in tracks that range from Western swing to New Orleans R&B. Berlin used to back Howard Armstrong, the Black string band pioneer who spent his final years in the Boston area. Armstrong had come up in an era when musicians might be asked to play hillbilly music one night and blues the next.

“Howard used to talk all the time about what he called skiffling, the string band ethos where you have to be prepared to know any song,” remembers Berlin. "You knock on the door and say, ‘I can play what you want to hear tonight.’ So this record is sort of a reimagining of what was going on at Berlin Hall.”

Berlin got to connect what he calls “two important threads in American music” when he introduced Armstrong to Kweskin. They first met at Armstrong’s Piano Factory apartment and then came together at a jam session in Fort Hill, the Roxbury home of the group once led by the charismatic and controversial Mel Lyman, a member of the Kweskin Jug Band. Fort Hill is sometimes referred to as a commune, while Kweskin has long preferred the term “community.” One thing everyone agrees on is that fixing up the Victorians in Fort Hill led its members to become very good at historic preservation. Kweskin spent decades as an executive with Fort Hill’s successful construction business, allowing him to play music when and how he wanted to.

Now retired, Kweskin mounted a major concert at the Regent Theatre last year to celebrate “Never Too Late: Duets With My Friends,” which found him collaborating with Jug Band member Maria Muldaur, his niece and longtime collaborator Samoa Wilson, and his granddaughter Fiona Kweskin. An after-party was held at Berlin’s Porter Square home, and Kweskin got to meet trumpeter and singer Annie Linders, Berlin’s bandmate in the rollicking traditional jazz combo Annie and the Fur Trappers. The band’s horn section is featured on the record, and Linders sings “Ducks Yas Yas.” It’s the kind of risqué song that was often part of early jazz and blues. Besides sex there were plenty of drugs in the pre-rock era, something captured by “Viper Mad,” which features Wilson’s wonderfully expressive singing. (In case that old jazz term is unfamiliar to modern listeners, the track starts with the sound of a joint being lit and inhaled.)

Advertisement

“Meeting Jim has been so refreshing, because the old folk music and blues are very closely related,” says Linders. “So I appreciate that when you’re playing with Jim, you can just strip down a song, and just play it and mean it.”

The album and release concert also includes such undersung Boston roots music figures as fiddler Matt Leavenworth and blues harpist and singer Racky Thomas. And earlier this year, Kweskin appeared at the Burren with an even younger group, the Stomp Street Serenaders. It’s the kind of lively Gen Z jug band that carries on a legacy that Kweskin is proud of.

When the Jim Kweskin Jug Band started, they were playing a style that had been largely ignored for decades. Their namesake proudly notes that there are now hundreds of jug bands around the world. (Many of them don’t have anyone blowing into an actual jug — Kweskin says that a jug band is simply “early traditional blues and jazz played on folk music instruments.”) Traditional jazz is likewise thriving and constantly reaching a new audience at informal gigs like the one the Fur Trappers play each Thursday at La Royal in Cambridge or at events like the Bay State Hot Jazz Festival, which Linders organizes each August.

In the ‘60s, the Kweskin band recorded with older blues artists like Sippie Wallace and Otis Spann. Asked if he now sees himself as a mentor, he demurs. “I don’t think a lot about the fact that I’m old and Annie is young. She’s a great musician and I get to play with her. I don't care how old somebody is. If they play good, I'll play with them.”