Advertisement

Review

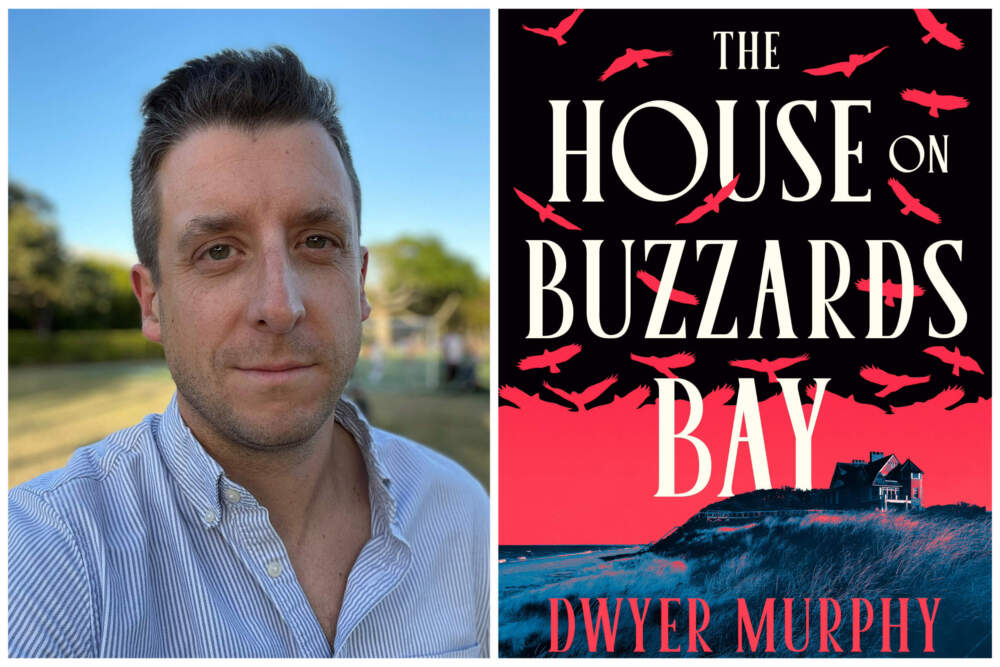

Dwyer Murphy's latest novel is a South Coast-set mystery

Wareham native and CrimeReads editor-in-chief Dwyer Murphy’s first two books — 2022’s “An Honest Living,” a New York crime thriller, and 2024’s “The Stolen Coast,” a heist story set in Onset, Massachusetts — earned rave reviews from prominent critics who were impressed by his modern, character-driven takes on the noir genre. Both earned “Editor’s Choice” accolades from the New York Times.

But among the plaudits, there were some caveats that might give a more discerning reader pause. Murphy’s books are said to rely heavily on atmosphere with little regard for plot; his pacing is “leisurely” (a polite word for sluggish); and his work is highly referential, leaning on familiar tropes and archetypes in a way that maybe implies coherence more than it actually delivers it.

All of this is certainly true of his latest novel, “The House on Buzzards Bay.” In it, Murphy demonstrates a knack for creating an uneasy mood. But in the end, what appears to be a calculated mystery proves to be merely meandering uncertainty. Three novels in a little over three years is a brisk output; one wonders whether a bit of a breather might’ve given him more time to figure this one out.

It all starts with a promising premise: A group of college friends, now in their late 30s, come together for a vacation on the South Coast of Massachusetts, hoping to recapture some of the closeness that has slipped away while they were building their own families and careers. They plan to meet at an old Victorian house owned by Jim, our narrator, who has deep roots in the small village and visits annually with his wife, Valentina, and their two children.

The guests include Maya, an artist, and her partner Shannon, who is expecting a baby; Rami, a globetrotting diplomat who seems to envy Jim’s settled domesticity; and Bruce, a novelist whose success has estranged him from the others. Despite Jim’s attempts to make everyone feel welcome, the vacation gets off to an awkward start, especially between him and Bruce. “There was, admittedly, a strange rivalry lingering between us whose exact origins and parameters eluded me whenever I got around to thinking about them,” says Jim. By the Fourth of July, things are so tense that a minor disagreement sparks a fistfight between them. The next day, Jim finds that Bruce has left without telling anyone.

To put it frankly, very little of what transpires after Bruce exits the story makes much sense. Shortly after his disappearance, a young woman named Camille arrives, claiming to be an acquaintance of Bruce’s. The group invites her to stay with them, inexplicably putting up with her probing, provocative questions and excessively familiar demeanor. Camille convinces them to host a seance in the house in the hopes of communicating with Jim’s great-great-grandmother, who we learn was a part of the Spiritualist movement once popular throughout 19th-century New England. She then abruptly switches gears, telling everyone they should try to contact Bruce because he is likely dead, producing his wallet as proof that something terrible has befallen him.

Advertisement

While the friends are confused by this, none seem especially alarmed — Rami even goes on to strike up a relationship with Camille. But after the two have a minor spat, she disappears as well. Jim is then drawn into a strange series of elliptical conversations with a teenager who is part of a gang that has been jailed for breaking into local cottages. The teen seems to know something important about both Jim and the house; what, exactly, is never quite spelled out. Meanwhile, strange noises make nights in the house uneasy, and the guests begin having unsettling dreams filled with sex, violence, infidelity and murder.

This pastiche of tropes — the mysterious stranger, the portentous dreams, the spooky old (and possibly haunted) house — are certainly intriguing. But Murphy does little more than introduce them, and the cadence with which he does so makes it seem like each new one is meant to distract you from thinking too hard about the last one.

At times, the characters themselves seem confused by Murphy’s plotting. At one point, Rami ponders about the missing Bruce “I keep thinking “if something did happen to him, why aren’t we looking?” Jim is constantly “at a loss,” perplexed by what people are telling him and befuddled by what’s going on, even when it’s patently obvious. Though some of his helplessness may be motivated, it’s also convenient in a story where a few well-placed questions would dispel a fair amount of the mystique.

This atmosphere of confusion and the eerie little setpieces Murphy designs are definitely compelling — you’ll want to keep turning those pages to see how all these seemingly disconnected elements fit together. That’s the real mystery. How is he going to make it all work? The disappointing answer is: he doesn’t. Nor does he really try to. The few revelations we do get at the book's finale are a letdown.

Reading “The House on Buzzards Bay” feels like trying to put together a jigsaw puzzle and discovering that the pieces you’ve been given all come from different boxes. They may look like they fit together, but they don’t. And even if you were able to force them together somehow, the picture they would make would be little more than an unsatisfying, incoherent jumble.