Advertisement

The public defender crisis isn't just a Massachusetts problem

Massachusetts has received national attention since it began dismissing criminal cases last month because of a pay dispute with public defenders. But it's not the only state struggling to pay for attorneys to represent defendants who can't afford their own.

" There are problems all over the country, and they're all the same problem," said Jennifer Nash, chair of the Oregon public defense commission. "It's extremely difficult to recruit and retain public defense lawyers. The pay is too low, and the caseload is too high, and the work is very difficult."

Across the country, states are struggling to maintain a roster of attorneys to take on public defense cases. The number of criminal cases is rising while more attorneys are balking at what they say are low rates of pay to do the work.

The legal bills for indigent defendants largely fall on the states. The 1963 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Gideon vs. Wainwright said the 6th Amendment right to counsel applies to criminal defendants in state, as well as federal, courts. But the ruling left it up to each state to determine how to provide legal representation for those who can't afford it.

Twenty three states, including Massachusetts, have a state agency that employs public defenders, according to the 6th Amendment Center, which tracks public defender spending. Each state has a different patchwork of state agencies, private attorneys and nonprofits helping provide attorneys for indigent defendants.

"States have the obligation of making sure that every person receives an effective attorney," said Aditi Goel, executive director of the 6th Amendment Center. "So the question is: how much and why should defendants pay the price for the state not being able to meet its mandate?"

For defendants, the lack of an attorney can result in a case languishing for months, sometimes longer. Several states have faced lawsuits in recent years over the number of people without legal representation and the length of time it takes to adjudicate their cases.

"America's dirty little secret is that there are thousands of people who go to jail without ever speaking to a lawyer," Goel said.

The pay for public representation is often much lower than what an attorney earns working for a private client, so many attorneys are opting out. Massachusetts attorneys who take public defense cases, called "bar advocates," say they're paid the lowest rate in New England: $65 per hour in district court, $85 in superior court and $120 for homicide cases. Maine and New York both pay about $150 an hour, New Hampshire pays $125 to $150, and Rhode Island pays between $112 and $142. These attorneys are essentially independent contractors, and most pay to run their own offices.

Advertisement

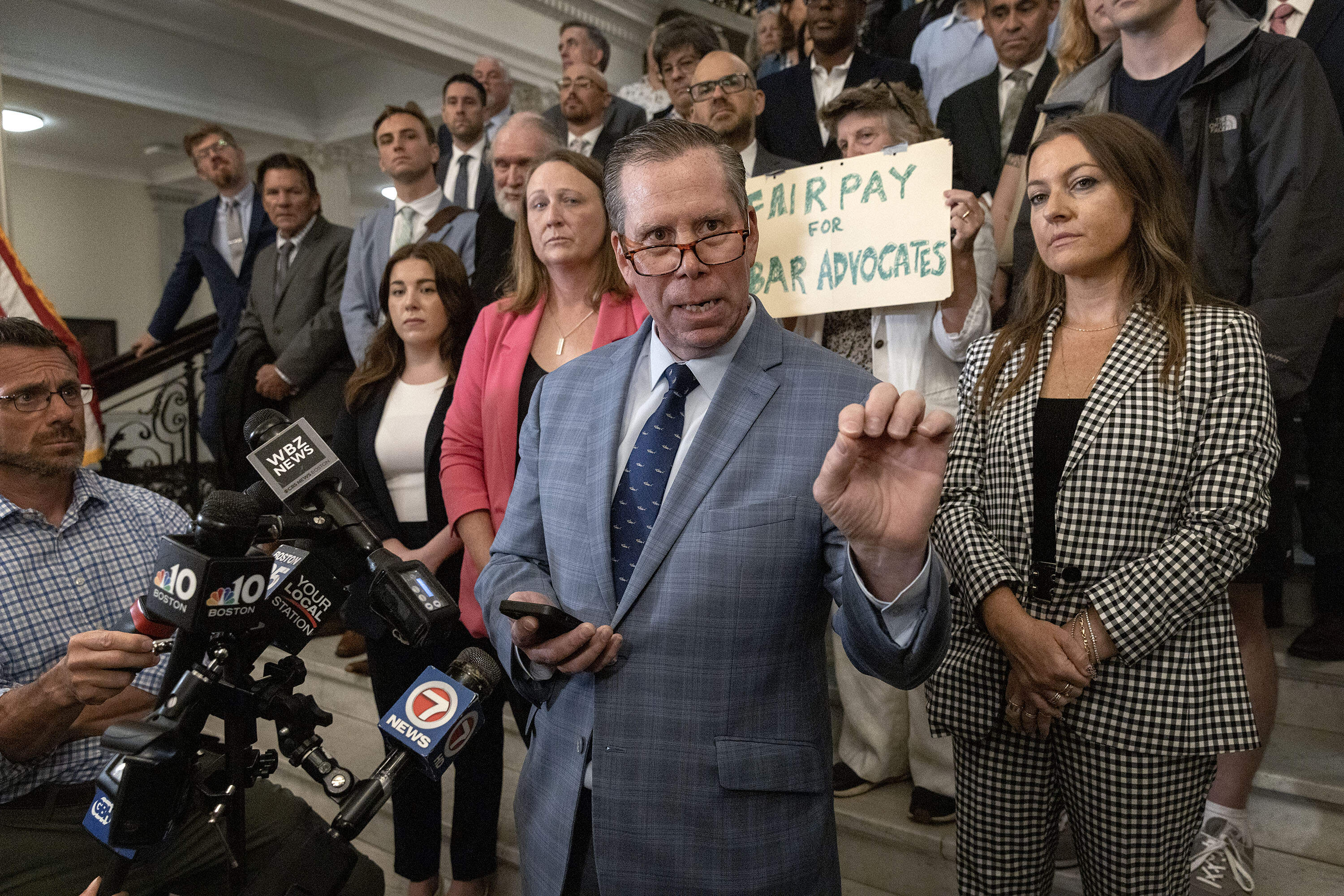

"If you want the right to counsel to continue, then you have to fund the defense program and there's a shortage of lawyers that are willing to do this for the current rate," said bar advocate Jennifer O'Brien, who is among the leaders of the effort to increase bar advocates' pay.

"The state certainly prosecutes enough people," O'Brien said. "They can't just pay for the prosecution side of it and then underfund the defense side of it."

"America's dirty little secret is that there are thousands of people who go to jail without ever speaking to a lawyer."

Aditi Goel, executive director of the 6th Amendment Center

Bar advocates in Massachusetts have been refusing to take new cases for more than two months as they push for higher pay. That's led to more than 100 cases being dismissed and dozens of people released from jail because of a shortage of attorneys.

Judges in Massachusetts are following emergency protocols from a state Supreme Judicial Court ruling that says if a defendant is not appointed counsel within 45 days, the charges are to be dismissed. If someone in custody does not have legal representation within seven days, they must be released.

At least one Massachusetts prosecutor says the office will refile the cases once attorneys are available. More hearings are expected that could result in additional dismissals without a resolution of the wage dispute.

The state public defender agency, the Committee for Public Counsel Services, estimates more than 3,100 people in Massachusetts currently do not have legal representation.

Other states facing this challenge include Oregon, where litigation is pending over unrepresented defendants. Jennifer Nash, chair of the Oregon public defense commission says more than 4,000 people in Oregon currently do not have an attorney. The state made efforts to reduce the backlog and temporarily increased the hourly rate for private attorneys who take public cases to start at $164 an hour. Oregon lawmakers, however, let the increase lapse, and the starting rate will go back down to $140 an hour.

" The system is broken," Nash said. "We are denying defendants the right to counsel when they don't have a lawyer and it is very problematic for crime victims who aren't having any resolution of their cases."

Maine is facing a similar crisis. The state expanded its public defender program two years ago, but lawmakers recently voted not to continue the same level of funding long-term. That's despite a high-profile incident last year when a judge reduced bail for a defendant because there were no attorneys available. Within days the man committed a violent crime and was killed in an armed police standoff.

Logan Perkins, a public defender in Bangor, says part of the problem is there are too many cases.

"The politicians and the prosecutors think that we need to be tough on crime, and we need to prosecute more people," Perkins said. "And they're increasingly unwilling to pay the cost to do that while providing them counsel."

In New York City, unionized public defenders averted a strike after reaching a tentative deal last month over better pay and smaller caseloads.

Attorneys say there are several reasons why this issue is coming to a head now. They cite a pandemic-induced backlog of cases, poor defendants' lack of political power, law school debt and a high cost of living.

Massachusetts attorney Lisa Newman-Polk says she stopped taking lower-level public defender cases eight years ago because of the pay.

"The rate is just so abysmal," Newman-Polk said. "Inflation has raised the cost of everything, and I think all of us know that just getting somebody to come to your house to fix something often costs substantially more than $65 an hour."

Massachusetts lawmakers have offered bar advocates a $20 hourly raise over two years. The offer calls for private attorneys to agree that another work stoppage would constitute evidence of anti-trust violations. Several attorneys say they won't accept that, and they want at least a $35 hourly wage hike.

"It's not sustainable," O'Brien, the bar advocate, said. "I will not go back if it's under the $35, and there are a great deal of attorneys like me who will not go back unless it's $35."

The jury is still out on whether some bar advocates might begin taking new cases and whether more charges will be dismissed.