Advertisement

Featured Book

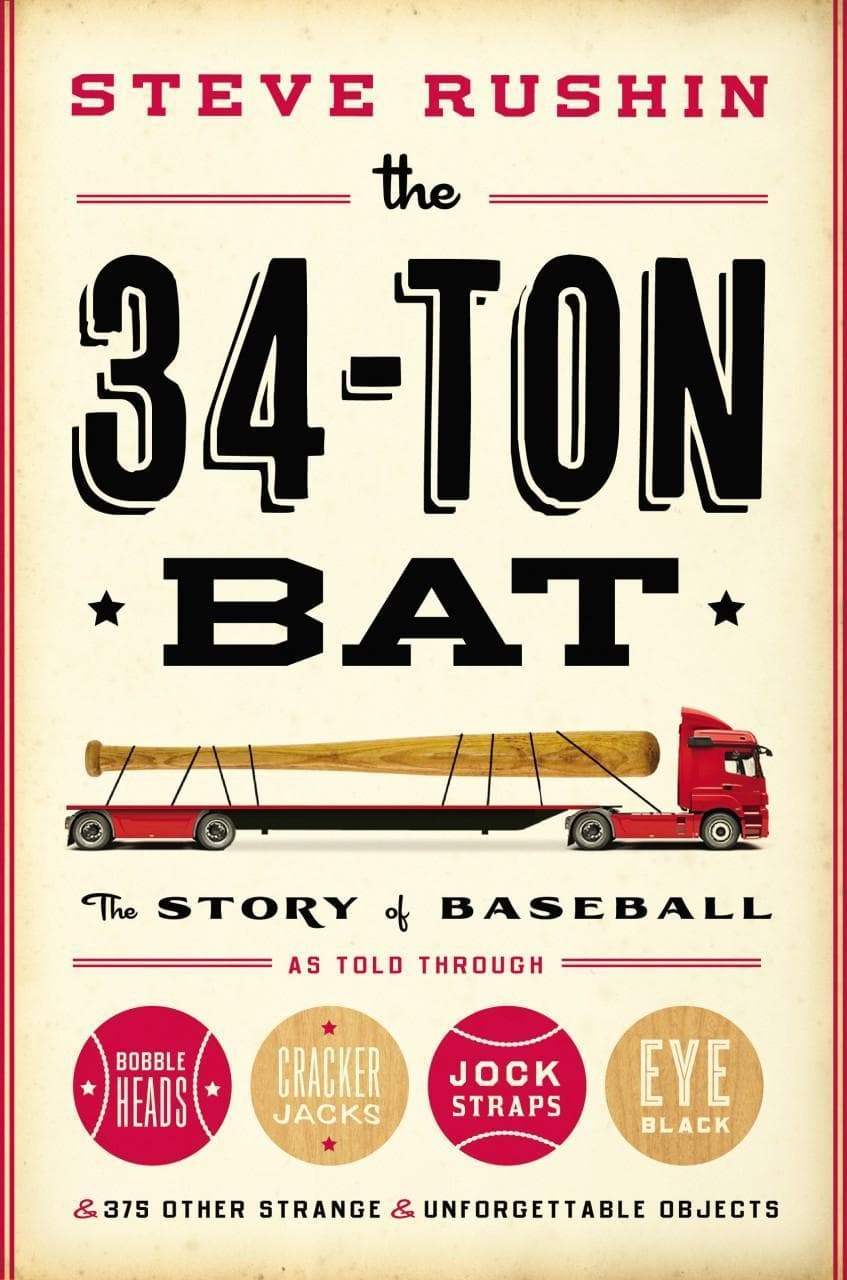

Steve Rushin: 'The 34-Ton Bat'

Resume

In the age of books with long subtitles, Steve Rushin has raised the bar. His new book is The 34-Ton Bat: The Story of Baseball as Told Through Bobbleheads, Cracker Jacks, Jockstraps, Eye Black, and 375 Other Strange and Unforgettable Objects.

Highlights From Bill's Conversation with Steve Rushin

BL: As the subtitle suggests, there are lots of other intriguing objects in your book and intriguing characters, too. And one of them is "Foulproof" Taylor. Tell us about "Foulproof" and how he earned his nickname?

BL: As the subtitle suggests, there are lots of other intriguing objects in your book and intriguing characters, too. And one of them is "Foulproof" Taylor. Tell us about "Foulproof" and how he earned his nickname?

SR: Well, Foulproof emigrated from England in 1907, went to his first baseball game a year later, became kind of fascinated by American sports, and he worked in a telegraph office in New York but moonlighted in the chorus of the Metropolitan Opera. And one night during the opera he was speared in the groin by a spear carrier and that night went down to the Bowery and bought some rubber cigars, which he put around some aluminum and he fashioned a protective cup — what he thought was the first protective cup — wore it the next night to the opera, asked the guy to spear him there.

The guy complied, happily, and he started taking this prototype around to New York boxing gyms and asking them to kick him in the groin. He then tried to sell this invention, the Foulproof Cup, to the New York State Boxing Commission because boxing had a real problem in the 1920s where a fight would end on a low blow and all bets then would be cancelled. So if a mobster at ringside had his guy losing, he’d just tell his guy to throw a low blow and all bets were called off and the fight was called off. And boxing really had to do something about these low blows, and Foulproof tried to sell the New York State Boxing Commission on the Foulproof Cup as he called it, and thereafter he always insisted on being called Foulproof Taylor.

BL: And eventually Foulproof’s invention made it into baseball, at least in a manner of speaking. You write in the chapter about Mr. Taylor, “His market research involved epic bouts of self-endangerment.” He went around ordering professional ball players to hit him over the head with bats, right?

SR: He talked his way into the Dodgers clubhouse and a few guys would sort of reluctantly tap him on the helmet with their bat, and then he’d say, “No, no, give me a real shot.” And they would always find somebody game enough to just whang him over the head with a Louisville Slugger. And he did the same thing with a prototypical football helmet that he’d invented. He butted heads with the Fordham Ram mascot, which was a live ram at the time. He would run head long into a granite wall.

As his great niece told me, he claimed to be fouled, as he put it, 30,000 times while testing the Foul Proof Cup. When I asked his great niece if he and his wife had had any children, she kind of laughed and said, “No, we expect that all of that quality control prevented him from having any children."

BL: Of Danny Goodman, the king of ballpark souvenirs, you write, “No idea was too crazy except for those that were.” Tell us about some of the ideas in the latter category.

SR: He was credited with the first guy to bring bobbleheads to the U.S.—plastic batting helmet day. He was quoted in the late 1950s as envisioning ballparks as sort of souvenir shops with the stadium attached, and that’s exactly what we have in modern day stadiums. He was really a visionary.

Bill's Thoughts on The 34-Ton Bat

"Foulproof" Taylor may be the most thoroughly bizarre character in Steve Rushin's new book. He is certainly the most thoroughly bruised.

Rushin also speculates on spectacles, as in the glasses worn by outfielders. They used to be called "smoked glasses." Several versions of them flipped up and down. Among the outfielders who didn't need them was Babe Ruth, who always insisted that somebody else play the outfield position where the sun was a factor. He could do that because he was Babe Ruth.

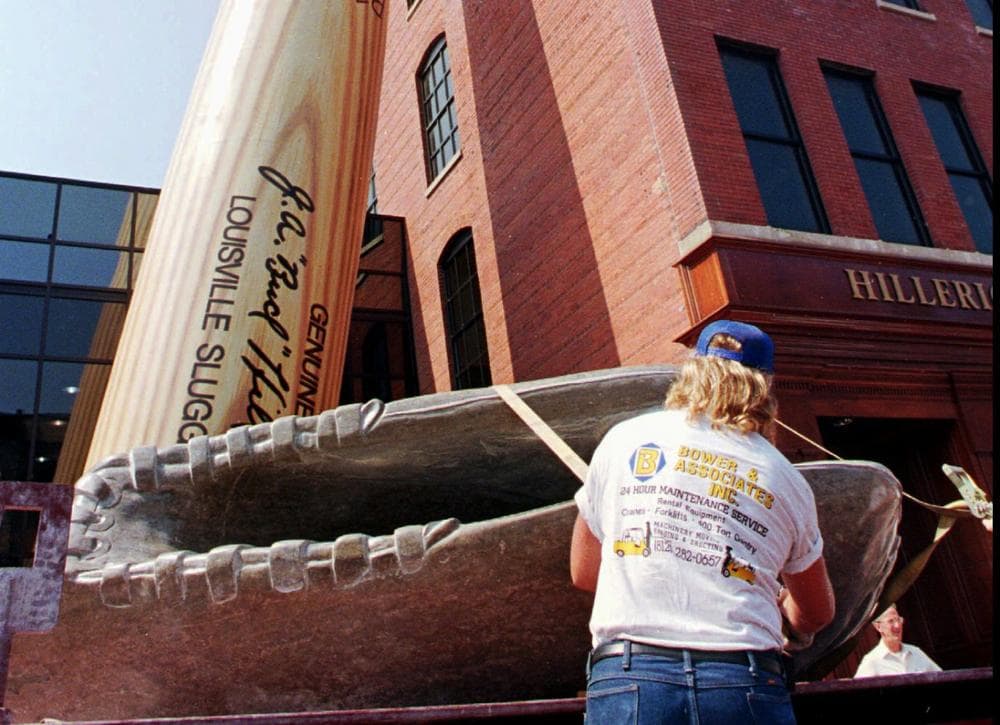

Elsewhere in The 34-Ton Bat there are stories of bobble head dolls, eye black, and various treats served at various ball yards over the years. There is also the 34-ton bat itself, which is made of "hollow carbon steel." Think about how much that bat would weigh if the carbon steel was solid. Yikes.

Because it's Steve Rushin writing about these things, they become very entertaining subjects.

This segment aired on October 12, 2013.