Advertisement

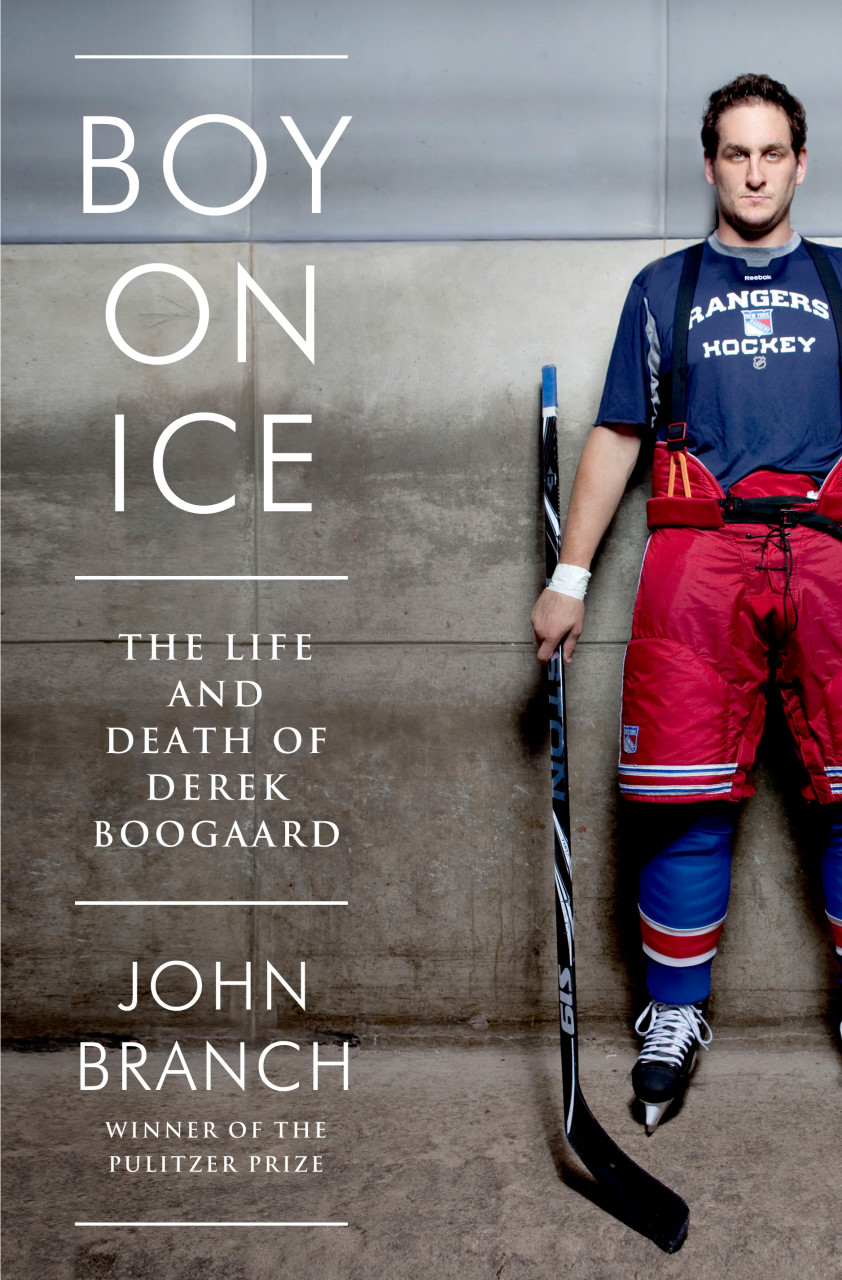

'Boy On Ice' Details Troubled Life Of NHL Enforcer Boogaard

For a brief and bloody time, Derek Boogaard was among the most feared players in the NHL. He spent nearly all of his six years in the NHL with the Minnesota Wild. He died of an accidental drug overdose in 2011 at the age of 28, which raised questions about the continuing role of enforcers in pro hockey. John Branch tells his story in "Boy On Ice: The Life and Death of Derek Boogaard."

Highlights from Bill's interview with John Branch

BL: John, we spoke a few years ago when you wrote about Derek Boogaard for The New York Times. He was a big guy, stood almost seven-feet tall on skates. Sometimes he weighed as much as 300 pounds. How early in his hockey career was he identified as what NHL teams call an "enforcer?"

JB: You know what, he was about 14 or 15. He was playing youth hockey. He was a decent player — nobody ever expected he would amount to much. And it wasn't until he very unexpectedly went ballistic on the ice one night in a small arena in Saskatchewan, and there happened to be scouts there.

He just started pushing kids around. They were getting beat badly. He started just taking swings at kids and scattered the opposing team and their coaches, like spooked cats almost. But it turns out the scouts were very excited about what they had seen. And that was when he kind of got put on to that conveyor belt toward where he became an NHL enforcer.

BL: Boogaard was beloved in Minnesota for five seasons. His jersey was an enormous seller. The team gave out bobblehead dolls of him, and they were the only bobblehead dolls that had bobbling fists as well as bobbling heads. But they traded him in 2010. Why?

JB: You know, his contract was up. He had been through substance-abuse rehabilitation the year before, which was kept a secret, so a lot of people did not know that. And he was beaten up. He had missed a lot of action because of injuries. And he was going to earn a lot of money, and the Wild said, "You know, we don't need to pay this guy this much money."

BL: The substance abuse is a particularly strong element in the book. Boogaard was constantly injured. He was constantly in pain. And you write that over one period of 33 days in 2008, Boogaard "received at least 195 hydrocodone pills from six NHL doctors, five of them affiliated with the Wild." Is it fair to conclude that the team and the league were complicit in Boogaard's addictions?

JB: You know, I would say you can draw your own conclusions. I think the family certainly believes that. Derek discovered that if he went to one doctor and had some procedure done and they prescribed him pills, if he had another procedure done, he could then get prescription pills from the next surgical procedure. And it became pretty obvious to him pretty quickly that the doctors were not speaking to one another.

BL: You also write about a phenomenon that you call "the circular culture of concussion denial" in pro hockey in general and particularly in the NHL. Explain what you mean by that term and what it had to do with Derek Boogaard.

JB: Derek, if you were to ask the medical reports, he had about three concussions during his NHL career. If you were to ask his family, they would probably look at it and say there was probably 10 to 12. Nobody ever really defined what a concussion means to Derek until very late in his career.

When he went to a doctor and the doctor explained, "A concussion is really when you get hit in the head and you black out for just a moment, even for a split second, and sort of shake your head a little bit and say, 'Whoa, what just happened?'" And Derek laughed at that and said, "Wow, well if that's the case then I've probably had hundreds."

And he was responsible for that too — enforcers need to be the toughest guys on the ice. If you say you're out with a concussion, doctors and team officials say, "Well, what does that mean? How badly are you hurt?" And they might even question your toughness. There are a lot of reasons why he would deny it. The teams then went ahead and denied it, too. They would never make it official that this is why a player was out, for a concussion.

Advertisement

BL: An autopsy of Derek Boogaard's brain indicated that he had chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), although he was only 28-years-old when he died. In the months before his death, Boogaard was displaying the symptoms of that condition. What were those symptoms and why was nobody around him paying attention to that?

JB: Nobody had linked those symptoms to CTE at that time. They saw Derek as depressed, and so people looked at him as lonely. They didn't really connect it to the drugs — and to, certainly, the concussions — unfortunately until pretty late. We'll hopefully see that change as we see that CTE can be diagnosed before somebody dies. But at that time, and still today, it can't be diagnosed until somebody dies. And so we don't know why somebody's acting the way they are acting until, unfortunately, they're gone.

Bill's Thoughts on Boy On Ice: The Life And Death Of Derek Boogaard

Derek Boogaard made it to the National Hockey League.

That's the bright side of his story.

[sidebar title="An Excerpt From Boy On Ice" width="630" align="right"] Read an excerpt from John Branch's "Boy On Ice: The Life and Death of Derek Boogaard" [/sidebar]

But he made it because he was big and because when he was still playing in one of the lowest levels of pro hockey in Canada, he went nuts one night, tossed aside a couple of referees, and challenged the entire opposing team to fight. They declined. A couple of scouts were at that game to check out several players who were not Boogaard. But when they saw how intimidating the kid who was bigger than anybody else could be, they wrote down Boogaard's name as a potential "enforcer" (aka "goon").

Once he earned a job with the Minnesota Wild, Boogaard became a fan favorite. They roared for the coach to put him on the ice, knowing it would mean a fight.

In order to keep his job, Boogaard played when he should have been healing. Through physicians employed by the team and drug dealers whom he met through other players, Boogaard acquired the painkillers that made it possible for him to do that. He acquired them by the pound. Attempts to help him recover from the addictions he developed were unsuccessful. He died from a combination of alcohol and drugs when he was 28.

John Branch's account of Derek Boogaard's life is sad, though given what we've learned about the lives and deaths of other NHL "enforcers," it's not shocking. What is at least surprising is that nobody connected with the Wild or the NHL — no team doctor, no trainer — has been indicted for dispensing medications so irresponsibly.

Derek Boogaard's death was the consequence of his own determination to get and keep a job in the NHL and the fabulously derelict conduct of his employers and the alleged "professionals" charged with treating him. But the culture of the league is also to blame. Nobody expected Derek Boogaard to score or to steal the puck. Boogaard's job was to stride out on to the ice and fight the other team's enforcer. As a consequence of that work, he suffered injuries to his hands, shoulders, head and brain. His pain was constant, as was his anxiety about keeping his job. If he didn't show up and fight, the Wild would find somebody who would. And his future was likely nil. The posthumous diagnosis of post traumatic encephalopathy probably explains his bizarre behavior in the months before he died, and certainly suggests that had he lived, his life after hockey would have been severely compromised.

The NHL has long maintained that fighting is intrinsic to the game, and that the result of its elimination would be more troublesome mayhem. The league has never acknowledged that damage to players like Boogaard is the natural consequence of that self-serving and cynical position. Nobody has offered proof that the elimination of fighting in the NHL would usher in chaos. The life and death of Derek Boogaard should haunt people who accept that hoary premise, but there's no indication that it does, or that it will.

This segment aired on October 4, 2014.