Advertisement

High-Interest Loans Tempt Families Waiting For NFL Settlement Checks

If you Google the words "concussion" "settlement" and "loan,” you'll find ads. Lots of them. And they're all variations on a theme: The NFL has agreed to pay former players up to $1 billion. No one knows when the payments will begin. And former players are struggling, sick, bankrupt. They need money. Now.

Then comes the hook. Or rather, the promise: “We can solve this problem for you,” the ads promise former players. "It's not a loan. It's an advance on the money you’re due. And if the settlement doesn't go through or if your claim is denied, you don't have to pay back that advance." The small print may mention that if you get the money, you’ll repay that alleged non-loan and interest of 40 percent...or more.

The former NFL players being offered these deals are especially vulnerable to the pitch-man's lure.

We first read about the issue in The New York Times. Liz Nicholson saw that article, too. It was all over her Facebook and social media feeds. But she says the news wasn't exactly new.

“All of the people in the NFL were very aware of what’s going on," Nicholson says. "In fact, there had been a letter that I think was sent out, I wanna say, a couple years ago, warning families about this very thing.”

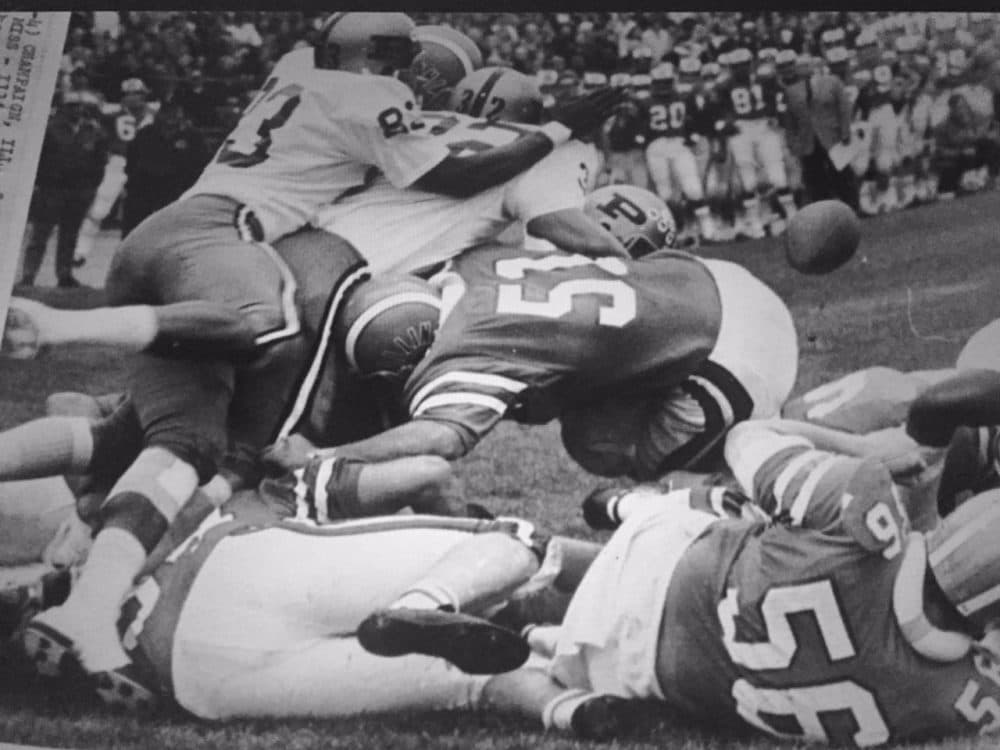

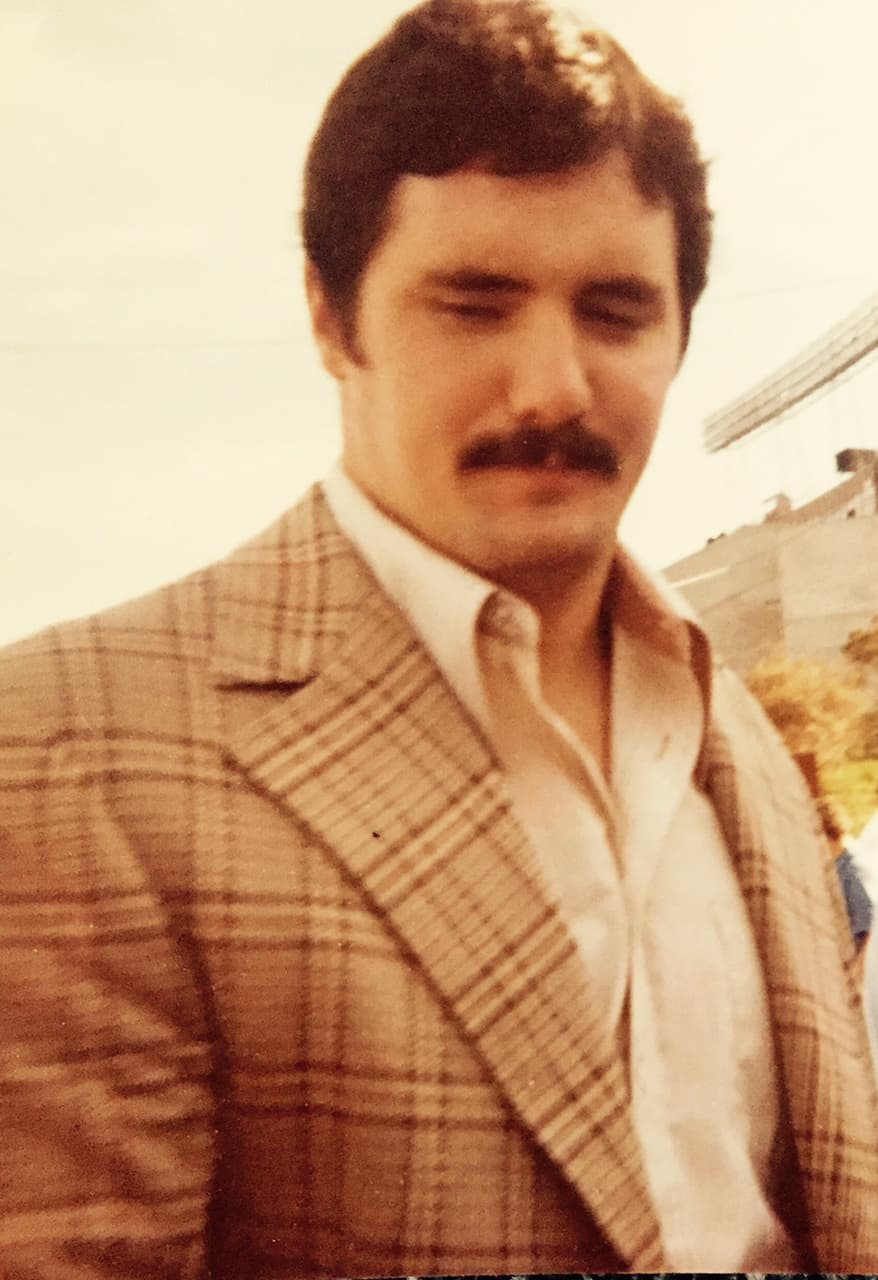

Liz Nicholson and her friends can't remember who sent the letter. It might have been from the Players' Association. Liz received the warning because she's the wife of Gerry Sullivan, who was a lineman for the Cleveland Browns from 1974 to 1981. She's also the Finance Director for the Senate Democrats in Illinois. She knows her way around a financial spreadsheet, and she would likely never recommend that someone take on a loan from an unregulated lender who charges upwards of 40 percent interest. But these loans aren't being offered to just anyone. They're being offered to former players who are showing signs of brain damage.

"So risky, so bad," Nicholson says. "I have a lot of love for my husband and his brethren in the NFL. I'm not saying anything disparaging against them. It's just that so many of them are suffering, and one of the biggest things, Karen, is that they lack impulse control. They’re not in the right frame of mind to be agreeing to these loans, and I know that from experience from my husband, Gerry.”

Advertisement

Liz and Gerry met long after his football career was over. He was divorced, with three daughters.

"When I first met Gerry back in 1997, he was $70,000 in debt to the IRS," Nicholson says. "He had so many issues going on. He could not manage his money.

"So we’ve been together a long time and been through a lot, a lot together. We had two years where I left him, due to his illness from football. I like to call it the football disease, because obviously you can’t diagnose CTE until postmortem."

For now, Gerry Sullivan's official diagnosis is early onset dementia. He was given that label when he was only 52 years old. Before that, doctors thought he was bipolar, because he had such dramatic mood swings and a difficult time controlling his rage.

"As a joke, people used to call Gerry — Gerry with a G — Scary Gerry. Now that I think back on it, it hurts my heart, because I know that Gerry was ill from football," Nicholson says. "It wasn’t that he was just this maniacal, violent human being. He was brain-damaged, and that’s why he acted out like he did.”

These days, doctors recognize mood swings and rage as possible signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, a degenerative disorder caused by multiple concussions and sub-concussive hits. But back when Liz and Gerry started dating, CTE hadn't yet been identified.

“So was Gerry already showing signs when you started dating? Like was this already happening?” I ask.

“I would say that yes, he was," Nicholson says. "He was showing signs, and I saw the signs and I chose to ignore them, you know, because I loved him, and I was literally so embarrassed by some of his behavior that I didn’t tell anyone about it for fear of people telling me to leave him. And I knew that, as an educated woman, I thought, ‘My God, am I like one of these women that’s gonna stay with a guy who has the capacity to be violent and scary?’"

Gerry Sullivan hadn't always been violent and scary. After he retired from football, he got a job — as most of the players from his era did. Sullivan never made more than about $90,000 a year playing football.

“He had a lot of good years. He’s a very, very bright, wonderful human being. Unfortunately there’s some — he thinks it’s embarrassing, but to me I tell him not to be embarrassed by this — there’s a lot of stuff on the internet that you can find due to our disability application process. As you could read, his rage and depression and lack of impulse control really fouled him up, and he was terminated because of his behavioral problems.”

So here's what Liz can't bring herself to say — the thing you can read about on the internet. Gerry was the Chief Operating Officer of a company that leased automatic ice machines. He was well liked. He did a good job. Until the disease took over, and he was fired for threatening other employees and punching holes in walls and ice machines.

“It’s painful to talk about. And it still is painful to talk about for a lot of women married to these fellas, because we love them, and we take care of them. But they are — they have serious problems, and it doesn’t help that they are larger-than-life characters in physicality and stature," Nicholson says.

It was about a decade ago that Liz left Gerry. She doesn't want to get into the details, but she says things were bad. Really bad. Divorce is common among those suffering from CTE.

But here's where Liz and Gerry's story is different from those of all but a handful of former NFL players and their families. Gerry applied for total and permanent disability from the NFL. He cited severe orthopedic injury and cognitive impairment as a result of his eight-year NFL career. The process took years. But on Jan. 1, 2005, the NFL approved Gerry's claim.

"Of course as the NFL continued to deny that there was a link between football and head injury, they were paying us for that very thing," Nicholson says.

Liz has never figured out why the NFL granted her husband's claim while denying so many others. Gerry went from having no money and no health insurance to receiving a modest pension and qualifying for Social Security and Medicaid.

"Had he not received that, I don’t know if I would’ve come back to our home that we shared together because things were going really, really bad," Nicholson says. "And I’m not saying I returned to him because he got the disability awarded. I returned to him because his spirits went up and he started getting medically treated. Because he needed to be treated — he needed to go begin the ungodly road of treating early dementia and depression and rage."

Today, Liz says Gerry's violent episodes have softened a bit, as the dementia has started to take over. Still, she loves him.

“My husband is very bright, and he’s one of the funniest guys you’ll ever meet. He’s very self-deprecating, he’s very witty. And even with all of the brain damage, Gerry’s strong enough where you can still see the shining light of his humor. And I think that’s something to be commended because a lot of people would have given up by now for the things that he’s gone through in his brain. The things that go on in his head, I can only imagine.”

Gerry is eligible for an award from the concussion lawsuit. All players who retired before 2014 are in, unless they opted out of the settlement. Some former players are still trying to block the deal in court in the hopes that they can negotiate a better one. But Liz says she's not in that camp.

"The whole thing about a class-action settlement, nothing's ever going to be perfect. You settle. That's the term. There are people in dire need right now. And it needs to be settled, and the football players and the brothers of Gerry's who need that money need to get that money."

It wasn't until two years ago that Liz started talking with the wives of other players. Before that, she says, she was too embarrassed. But now the women swap stories through a private Facebook group. They no longer need to feel alone and isolated. The group has more than 2000 members.

Liz knows some families are desperate for the settlement. She understands why they're considering the high-interest loans. If the league hadn't granted his disability claim, Liz says that she and Gerry might be that desperate.

"I don’t know if he’d be alive today," she says. "I don’t mean to say it like that, but it saved Gerry in a way.

“But had he not gotten that, like all these other players didn’t get, of course an award like this might seem very promising, you know, because he’d have no money."

It could take years before the settlement starts paying out, and it could take even longer before a player's claim is approved. All the while, interest will be piling up at the rate of 40 percent or more.

And at the same time, the amount of money that player will receive from the settlement pool will be getting smaller. Much smaller. It's a sliding scale. The older you are, the less you get paid. So, by the time the NFL pays up and then the lawyers take their share and the lenders take their share, there might be nothing left. Liz is worried that some players won't even bother to pursue their claim — or seek treatment — because of the amount of money they would owe.

Liz Nicholson has considered all the ways in which these loans could go wrong for men who are suffering from the same condition as her husband. But she's spent less time considering what she would say if one of her new friends asked for advice on whether to take one.

"You know what? I would never judge anybody else in this world of the football disease, as I call it," Nicholson says. "I would never judge them. But what I would tell these women is, hold off. As much as you can."

This segment aired on May 21, 2016.