Advertisement

Steve Young Remembers His Days As The USFL's $40 Million Man

Steve Young is in the Pro Football Hall of Fame for lots of reasons, all of them having to do with the way he performed as a quarterback for 15 years in the National Football League, more specifically, the last 13 years of that span, when he was with the San Francisco 49ers. He led them to victory in three Super Bowls.

But Young began his professional career in 1984 with the late and not particularly lamented United States Football League. He played for the Los Angeles Express. After he signed his first contract, his agent, Leigh Steinberg, began calling Young “the $40 million man.” Young, for one, was not amused.

When he sat down for an interview with me, I didn’t think Steve Young would be so excited when I said I thought we should talk about the early days of his pro career.

"Oh, great. That’ll be fun," Young said. "Oh my gosh, that’s one of my favorite subjects, to be honest with you."

'The $40 Million Man'

Perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised. Young was young. He anticipated that a fine career at Brigham Young University would seamlessly develop into glorious days in pro football. And, I mean, who wouldn’t want to reminisce about being “the $40 million man?” Who wouldn’t be thrilled to recall that he once passed up an opportunity to play in the NFL, where he’d have been a back-up quarterback, to be billed as the most lavishly compensated athlete…ever.

"The nickname, huh. Well, Roger Staubach was my hero. I wanted to play. At the same time the USFL was really hopping. They had signed Reggie White. They had signed Herschel Walker. And so when they signed me they took an annuity that…I don’t want to make light of it. I mean, to fund the annuity was a million and a half dollars. And if you took the payments for the next 50 years it would total $40 million. And so, they said that I signed a contract that was worth $40 million," Young says.

"And so immediately it was world news: An American athlete’s been paid $40 million. Whooph. It hit me when I signed the contract, I want to say, at the Beverly Wiltshire Hotel in LA. I’ve never had this happen in my life except for this moment, where I got lightheaded and started to faint on the camera. And I’m like, ‘Oh, my gosh, I’m going down! I'm going down! I’m completely overwhelmed and this is…' And so I grabbed the table behind me and kinda fell into it, and I was like, 'Oh, excuse me.' And I kinda regained myself."

Advertisement

Although Young would never see the lion’s share of that $40 million, before he’d tossed a single pass as a pro, according to the hype, Steve Young was making double what Magic Johnson and Wayne Gretzky were pulling in. Overnight he became exhibit “A” for the case that the inmates had taken over the asylum, at least in the sports world.

"I just kept thinking to myself, 'Man, if I’m gonna be the $40 million man, at least give me $40 million. I mean, gee…'”

"People reacted. It was visceral. People responded, like, 'This world’s gone crazy. And the reason why it’s gone crazy is because Steve Young’s being paid $40 million.' So it didn’t matter how I played. My mom, that season in the stands, she’d gone to her first pro game, I want to say the New Jersey Generals down in New Jersey. I threw an interception, or something bad happened, and all of a sudden in the corner of the end zone a chant started, '40 million down the drain.'

"And so the whole stand started doing it, '40 million down the drain.' My mom was sitting there, like she just couldn’t take it. And she stood up and turned to these guys and said, 'It’s not $40 million, it’s an annuity!' They’re like, 'What’s an annuity, sit down, you’re the ugliest woman…' It just got really ugly. I just kept thinking to myself, 'Man, if I’m gonna be the $40 million man, at least give me $40 million. I mean, gee…'”

Ground Support... Or Lack Thereof

Forty million dollars wasn’t the only thing Steve Young didn’t get as a member of the Express. Playing in the spring and summer for a league on shaky legs, Young, his teammates, and the rest of the players in the USFL didn’t get a lot of the amenities pro athletes had learned to take for granted…amenities like transportation that didn’t scare you to death.

"One time we were playing the San Antonio Gunslingers, and it was 105 degrees. So after the game, most of us were on IV, we were all struggling. We’re on this plane and Bam! Something hits the plane! It just rocked the plane! We're all kind of jostled out of our seats. We’re not even moving! We’re parked! We’re like, what is going on? And Don Closterman, I love the guy, he comes on and says, ‘Fellas, the equipment truck has backed into the engine, and it’s created a hole in the engine. But I flew in WWII, and I could tell you that this is going to be fine. We’re definitely flightworthy.'

"And we all stood up and we're like, 'You flew? In w..whaa — there’s a hole in the engine? No.' We went out and looked at the engine. There’s this huge steel piece that’s just ripped off the engine. You could see all the stuff that’s going to move around. We’re like, 'Maybe, maybe it’s just cosmetic. But I’m not..I’m not doing that. We’re outta here.' I remember making my way back from San Antonio on a commercial flight with all these other guys, that was just…that was…that was the good year."

Let's move on from the year of the airplane with a hole in its engine and the optimistic general manager who flew in World War II to the bad year when the players on the L.A. Express learned the team was lacking an owner.

"I don’t remember exactly how it happened, but he got indicted for ... something. Ugh. Then it got crazy, because there was no money for anything. And you take things for granted, like someone cutting the grass for practice. Or someone bringing the footballs. Or a copier. And, well, someone’s friend, JoJo Townsell’s friend can cut the grass. And then how are we going to take down the game plan? Well, someone’s going to bring in 15 different notebooks and we’ll just kinda do it by hand. And they had to pick and choose who to pay."

I suppose as a quarterback, you’d urge the owner to pay the offensive linemen first.

On the good weeks, of course, everybody got a check. It was on one particular payday halfway through the season when alarm first spread throughout the work force.

"And that one Monday, the woman who was running payroll said, 'Hey, you gotta go to the bank. If you’re gonna get paid, you gotta go to the bank.' And so there was this Cannonball Run from practice where the whole team’s in a different car trying to pass each other down the PCH to get to the bank to be the first one to get their money. Ahh…remind me of some funny stories."

"And you lost some guys, right?" I ask. "Some guys didn't get to the bank?"

"Yeah, some of the guys didn’t get paid, and they just quit playing. That was it. So, they were done. It was like, 'Oh, man, sorry you didn’t get paid. See ya later.'”

The Unglamorous Life Of A Quarterback

It was perhaps unsurprising that even with “$40 million man” at the helm, the L.A. Express had problems drawing fans. The lack of interest led the Express to add a line to the quarterback’s job description.

"I used to get stacks of tickets and try to hand them out around the Coliseum before the game. But it just didn’t matter because you could put 5000, even 10,000 people in the Coliseum and honestly, it looked like nobody was there. So I had to move the huddle back, because the guys on the defense would hear the play: 'Oh I heard it was a pass.' I’m like, 'Oh geez.'"

"So the final game, the league decided it was so embarrassing to play at the Coliseum that we were going to go up to Pierce Junior College. We get on the bus and the bus driver says, 'Hey, I can’t drive until I get paid. Cash only.' And then there was a rebellion in the back of the bus, 'Don’t pay him; let’s just go home.' We’re like, 'No, we gotta go play. You know, were playing Doug Williams and the Arizona Wranglers. We gotta get up there.' So this is a good football team that’s now having to put up with this insanity."

"You and I are laughing about this now, but I wonder if it must have been pretty frustrating and even depressing at the time?" I ask.

"Yeah, for me, when you’re 22 and you want to be Roger Staubach, this doesn’t feel like you’re going to get there. You can see that I have a very warm spot in my heart for the people that I was with, the good football that we played, what I learned. It was really a great time. But you had no appreciation for it at the time, that’s perfectly said."

Though the Express made the playoffs after going 10-8 in Young’s first season, and despite one occasion upon which he became the first pro quarterback to pass for more than 300 yards and run for more than 100 yards in the same game, Young felt as if he was spinning his wheels.

"There was this feeling like, you know, you’re just wasting your professional years and you’ve gotta get to the NFL, ‘cause this thing is not gonna make it. [laughter] Little did I know… get to Tampa Bay and woaaah!"

"Well, I was gonna say, once you got to the NFL everything was great, right?" I ask him.

"It was brutal. I thought, 'My gosh, this is worse.' That was a shock for me. To come to the NFL and have some things that were worse."

"Yeah. Oh, perfect! Yeah. I remember I landed in Tampa Bay, and right next to the facility there was this thing called the 'Buc Inn'. Ooh. It was the ultimate roach motel. It was brutal. I thought, 'My gosh, this is worse.' That was a shock for me. To come to the NFL and have some things that were worse."

A Different League, A Different Lifestyle

During Young’s two years with Tampa Bay, the Buccaneers won just four games. They lost 28.

"The years were chaotic, but yet, I mean, I was playing. Playing was what I wanted to do. I mean, the reason Bill Walsh took me to San Francisco was what I had done with the Buccaneers and the Express. And I remember him saying, 'I’m really impressed with how you play.' And I’m like, 'Jeez, Bill. You gotta have a keen eye to catch all that, with what I’ve been through.'"

Walsh was the Head Coach of the 49ers, who were owned by Eddie DeBartolo. He didn’t bounce his checks…even the big ones he wrote to star quarterback Joe Montana.

"Was there a moment when you got to San Francisco where you suddenly could say 'Aha! This is what it’s supposed to be like! I get it?'” I ask.

"Oh. Oh, the first minute. I came off the plane, landing in San Francisco. I went down to the Redwood City training facility, which is in the middle of a — kind of a public park. And Eddie Debartolo was there. And the first thing he said, he gave me a big hug, a kiss on the cheek, a scratchy beard, you know. And he says, 'Welcome to the family. Anything you need, you let me know.' I’m like, 'Holy cow.'

"Everything about what was happening in San Francisco felt comfortable. The teamwork, the comradery, the way we practice. I mean, honestly, I knew that this was the place I wanted to be. But my gosh, I do not wanna watch Joe Montana play football. I wanna go play. And so that was the beginning of what was in the next four year odyssey in the story."

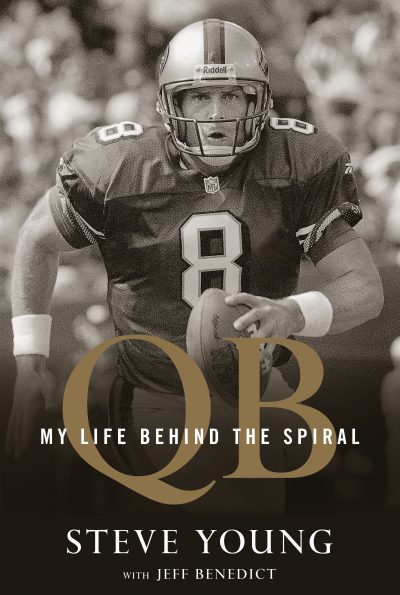

Good company as Steve Young is, we don’t have time to allow him to talk about how he eventually outlasted Joe Montana in San Francisco. But you can find his stories about those days and more in "QB: A Life", the book Steve Young has written with Jeff Benedict.

This segment aired on November 19, 2016.