Advertisement

40 Years Before Title IX, A Rural Oklahoma Team Elevated Women's Basketball

As a writer, Lydia Reeder is twice fortunate.

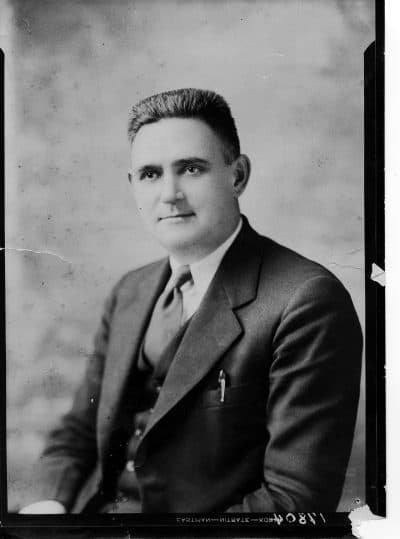

First she’s related to a man any writer would recognize as an intriguing subject. Her grandmother’s brother was a fellow named Sam Babb. He grew up in Missouri over 100 years ago. Sam’s dream was to become a preacher, like his father.

Ironically, it was Sam’s father who derailed that dream. He was a man quick to anger, and on one particular occasion when Sam was in his teens, his father exploded at two of Sam’s younger brothers for failing to clean the mud off his saddle after he’d returned home from a ride on the preaching circuit.

"So when he found out that it wasn’t clean, he became very, very angry," Reeder says. "And Sam jumped in to protect his younger brothers, and his dad had found what was called a trace chain, which hooked up the horses to the wagons. It’s a big chain, and injured Sam by lashing out with the chain. Back then they didn’t have antibiotics. The injury became infected, and eventually he lost his leg right above the knee. Because he had lost a leg, the ministry would not accept him into the school, because only a whole man can preach the word of God."

Putting that mad reasoning aside, we can move on to the other reason Lydia Reeder is fortunate, which is that her grandmother, Sam Babb’s sister, collected everything she could find about Sam. That’s how Lydia discovered what an impact her grand uncle — foiled in his attempt to become a preacher — had made as a basketball coach. An impact so impressive that Lydia’s grandmother campaigned to get Sam into the Oklahoma Sports Hall of Fame.

"His achievements had been lost to history, and she wanted to make sure that they were rewarded," Reeder says.

Becoming Coach Babb

Babb hadn’t planned to become a basketball coach. In the early '20s, he earned a masters degree in education at the University of Oklahoma. He became the superintendent of schools for Custer County.

Babb was in charge of everything school-related, including hiring the man who would coach both the boys’ and the girls’ basketball teams. He picked the wrong guy.

"Well, along the way, this coach had an inappropriate relationship with one of his students," Reeder says. "And the newspaper editor — his name was Buster McElhaney — found out about it and splashed it across the front pages of this little town newspaper. And the coach was married and had children, and they left town in the middle of the night."

Rather than hire another coach the next morning, Sam Babb added a line to his resume. He’d be the basketball coach, as well as the superintendent of schools.

Advertisement

Babb found he loved coaching, and he was good at it. He moved from the high school ranks to what passed for women’s college basketball at that time. The early 1930s found Babb at Oklahoma Presbyterian College in Durant, where he single-handedly assembled a team.

"In rural Oklahoma and in that region, there were lots and lots of potential players, and he would drive around the countryside going to see the players and meeting their parents," Reeder says. "And as a lot of the players I interviewed told me, when he drove up in his little Ford Roadster, they all thought a rich man had come to call, because they were all very poor."

Athletic Scholarships, 40 Years Before Title IX

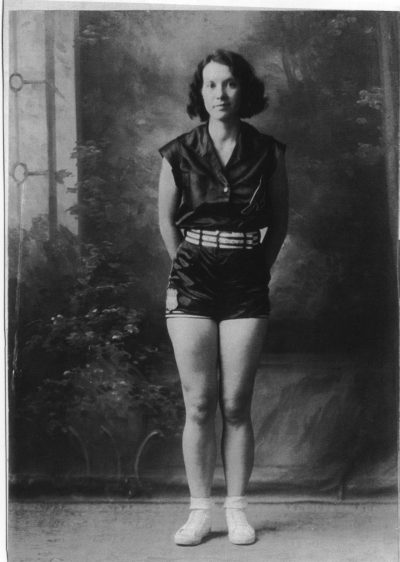

Oklahoma farmers had no monopoly on poverty during the '30s, though they were among the league leaders in that regard. But Sam Babb in his Roadster brought those farmers hope, at least regarding their daughters. One of the young women whom Babb visited was Velma Bell Harris, though she would not answer to that name.

"Her nickname was given to her by her sister, because she looked like just the cutest little baby doll, so she was called 'Baby Doll' for a long time, and then just 'Doll,'" Reeder says.

What Doll Harris — 5-foot-2, maybe 100 pounds — would eventually offer Sam Babb was tenacious defense and dependable shooting. What Coach Babb could offer in return was the opportunity to get off a dusty farm.

"Financial aid. A college degree. Her father did not have the money to send her to college, and she never would have gone if it hadn’t been the offer from Sam," Reeder says.

Babb had worked out a way to give athletic scholarships to women 40-odd years before Title IX. Doll Harris and her teammates worked part-time jobs to pay for their books, but their tuition was waived. And they played competitive basketball during a time when organizations such as the National Amateur Athletic Federation, sponsored by the U.S. Government, thought that was a very bad idea. Within the federation, the women’s division had friends in high places.

"When Mrs. Herbert Hoover took over, they went around systematically eliminating highly competitive sports from all of the universities," Reeder says. "They started a PR campaign that actually worked, and questioned whether women were emotionally or physically capable of performing those kinds of athletics."

Fortunately, the first lady’s influence did not extend to Durant, Oklahoma, where Sam Babb was building a juggernaut around Doll Harris. But the pernicious presumption that women shouldn’t sweat competitively limited Babb’s attempts to find worthy opponents. The Oklahoma Presbyterian College Cardinals played a few other schools, but their serious competition came from women’s teams sponsored by businesses.

'They Wanted To Beat Babe Didrikson'

In 1931, the most prominent among those teams was the Dallas Golden Cyclones, who worked for Employers Casualty Insurance ... as basketball players. The Cyclones were AAU defending national champions, and at the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles, one of them would emerge as perhaps the most famous female athlete of the first half of the century. She was Babe Didrikson: track star, champion golfer and high-scoring forward for the Dallas Golden Cyclones.

"They wanted to win, and they wanted to beat Babe Didrikson," Reeder says of the Cardinals. "And when they found out they were going to play the Golden Cyclones, it changed everything for them, and they worked harder."

Doll and the rest of the Cardinals, some of whom were as young as 16 and 17, earned the right to challenge the older, semi-professional Golden Cyclones by going on an extended road trip and beating everybody who’d play them. That led to an invitation to the AAU Championship Tournament in Shreveport, Louisiana, in early 1932. The Cardinals advanced to the final against Babe Didrikson and the rest of the Cyclones, thereby delighting the citizens of Durant.

"The rest of Oklahoma, who had read about the Cardinals, were definitely rooting for them, but I don’t know that they thought they could win," Reeder says. "And, of course, Sam always thought they could win, so. And he got quite a crowd to drive into Shreveport from Oklahoma to root for the Cardinals."

That crowd wasn’t disappointed. The defense Sam Babb had taught the Cardinals to play limited Babe Didrikson’s effectiveness. Doll Harris, who had excelled throughout the tournament, drew enough attention to free up some of her teammates, one of whom, Lucille Thurman, sealed the Cardinals' victory with a late basket.

"Oh, my gosh — they were overflowing with joy," Reeder says. "It was an immense achievement for them. Back in Durant, Sam and a couple of the other organizers back there had secretly arranged a surprise town parade, and, sure enough, hundreds of people turned out, because they knew they were coming home."

Overcoming The Odds

To say the Cardinals returned in triumph might be an understatement, especially as regards their star, Doll Harris. Perhaps to the surprise of some, she was named captain of the all-tournament team.

"I don’t know that she was that surprised," Reeder says. "But, she deserved it, and the Associated Press named her the top female basketball player that year. She was better than Babe Didrikson that year. So she won fans all over the country. I saw from her scrapbook postcards from Connecticut and other places, telling her how much they admired her."

"The rest of Oklahoma, who had read about the Cardinals, were definitely rooting for them, but I don’t know that they thought they could win."

Lydia Reeder

Of course Cardinals coach Sam Babb was admired, too, at least by those who acknowledged that in 1932, women should have as much right as men to excel at basketball and various other endeavors. Sam Babb’s quiet determination to demonstrate that now-obvious truth was one of the things that most impressed his grandniece.

"Writing about him and his life taught me how to persevere, because I think perseverance was one of the greatest qualities he gave the Cardinals," Reeder says. "Teamwork and sacrifice and perseverance. Because it took a while for me to gather all of the information and then to find and set aside time to write about it, and come up with the exact right way to tell the story. And eventually I realized that, 'Oh, yes. My Uncle Sam had taught me how to persevere.'"

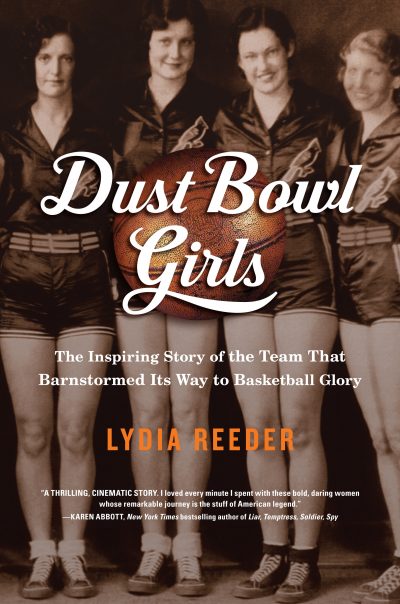

By the time she’d finished her book, "Dust Bowl Girls," it had also become obvious to Lydia Reeder that Sam Babb deserved the recognition her grandmother had worked so hard to get him, that he shouldn’t be forgotten. Nor does she think she’ll ever forget the young women Sam Babb coached.

"To me, the players seemed like real-life superheroes," Reeder says. "Because they seemed invincible back then, during a time when everyone felt so vulnerable."

Certainly the depression was such a time, albeit not the only one.

Sam Babb had imagination enough to see how good his players could be before they could see it, and the players found joy in the opportunity he provided. What chance does feeling vulnerable — in any time — have against imagination and joy?

This segment aired on March 4, 2017.