Advertisement

'Prince' Hal Chase: 'The Babe Ruth Of Ballgame Fixers'

Resume

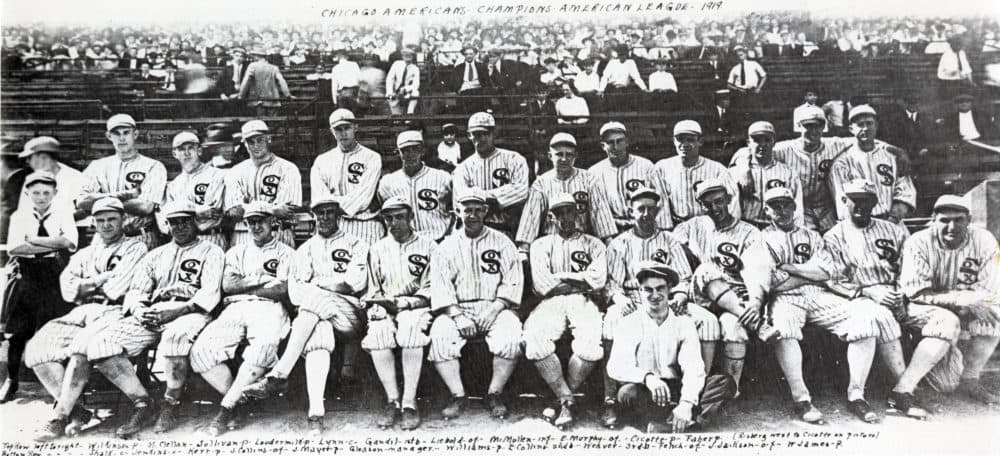

OK, free association time. I say "crooked ballplayers," and you say ... "Chicago Black Sox, 1919," because eight of the White Sox conspired to throw the World Series that year. Or maybe you say, "Pete Rose," because he acknowledged that he bet on games as a manager, unless it was one of the days when he didn’t acknowledge that.

But your free association probably wasn’t "Hal Chase." Maybe it should have been. And maybe, after you hear his story, it will be.

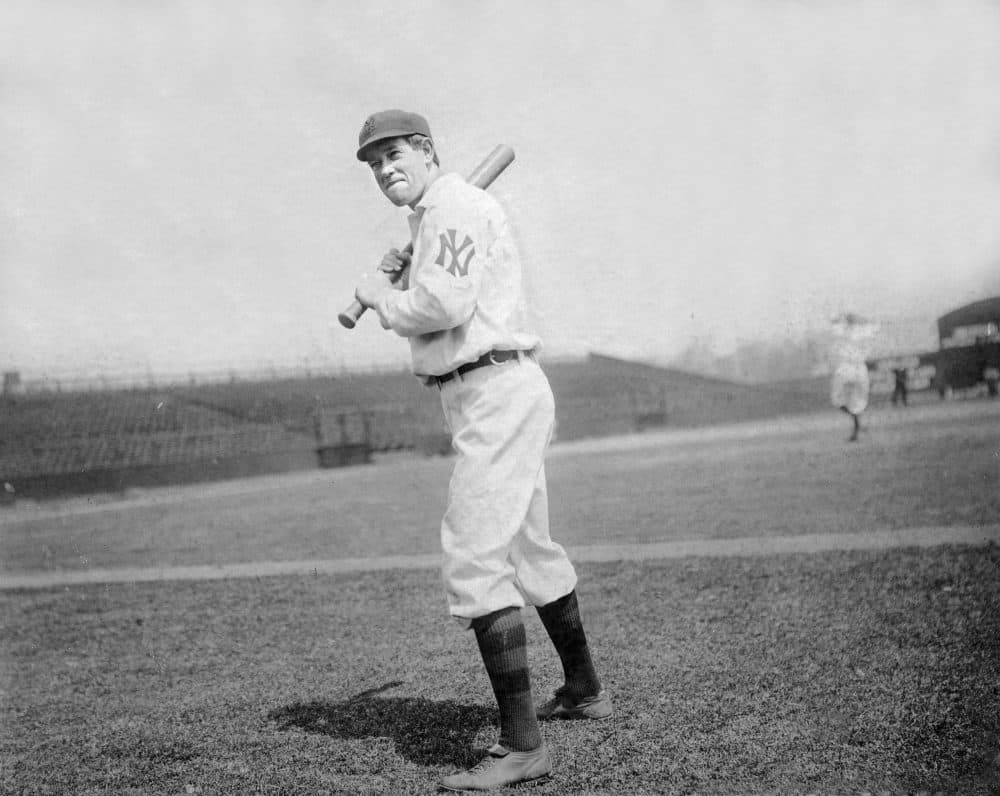

Hal Chase broke into Major League Baseball as a first baseman with the New York Highlanders, destined to become the Yankees. This was in 1905. By then, fixed ballgames had been common for some time.

"Baseball and crooked baseball grew up together, good twin and evil twin," baseball historian Charles Fountain says. "The first game-fixing scandal was three months after the end of the Civil War."

Fountain says there were even rumors of a fix at the first World Series, in 1903.

"There were rumors of games being fixed whenever games were played, literally," he says.

Into that baseball era came Hal Chase. He was handsome and personable. The New York writers soon dubbed him "Prince Hal." He was also, by all accounts, a bright and observant fellow. He could see the signs outside some ballparks that read, "Place your bets." And he was a terrific player.

"The people who saw him play said that he was the best defensive first baseman that they had ever seen," Fountain says. "These are people that saw all of the Hall of Famers: George Sisler and Bill Terry and Lou Gehrig. And everyone felt that he would have been a lock for Cooperstown, had he been a player who concentrated on baseball."

Rumors And Whispers

Alas, Chase didn’t do that. Maybe it was in part because he was contemptuous of his less talented peers, which, as far as Chase was concerned, meant all of them. One anecdote about an especially good play by Chase so illustrates:

"A writer came up and said, 'Good job on that,'" Fountain explains. "And he said, 'I could make plays like that every day, but I’m afraid of cutting loose, because I’m afraid of hitting one of those dopes in the head.'"

The first indications that Hal Chase was supplementing his income as a ballplayer by partnering with gamblers came in 1907. Some of his teammates became suspicious. The front office didn’t want to hear about those suspicions.

"This was one of the great stars, and no one wanted to know the truth," Fountain says. "It was much better for the game if it remained whispers. Rumors weren’t good, but proving those rumors to be true would have been lethal."

So Chase kicked the odd ground ball away or lost a crucial pop fly in a sun shining only on him. And sometimes he got more creative.

"He would, in the locker room, go to Player A and say, 'Do you know what Player B said about you?'" Fountain says. "And he would then go to Player B and say, 'Do you know what Player A said about you?' And, in so doing, would create dissension and cliques in the locker room. And if players are distrustful of one another, it’s an easy task to go up to one of them who’s frustrated and say, 'Hey, you wanna get back at all those guys? What do you say we let the other team win again today? And here’s 500 bucks for your efforts.'"

"Everyone felt that he would have been a lock for Cooperstown, had he been a player who concentrated on baseball."

Charles Fountain on Hal Chase

Over the last seven years of his major league career, Chase switched teams five times. In New York, Chicago, Buffalo and Cincinnati, managers tried without success to get him to play it straight. Opponents who’d come to know Chase well sometimes taunted him by shouting, "Hey, Hal. What are the odds on today’s game?”

'What A Prince Of A Guy He Was'

And then, in 1918, Chase became too ambitious. He was with the Reds by then, and more and more of his teammates had begun to resent that their efforts to win were so often in vain.

"Christy Mathewson, the former Giants star, was the manager of the Cincinnati Reds at the time, and a number of the Reds came up to him during the season and said, 'Chase is throwing games. He’s reached this player. He’s reached that player,'" Fountain says. "And they documented specific games, and they documented specific players. They pointed to 27 games where they felt that Hal Chase may have cost them that win."

The disgruntled Reds — the guys inclined to play games rather than fix them — urged manager Mathewson to try to get Hal Chase tossed out of baseball, and Mathewson went to the league office with their plea.

And, against all the odds, considering that Chase was hardly the only ballplayer working with gamblers in those days, the National Commission, precursor to what is now the Office of the Commissioner, held a hearing.

"And Hal Chase came with a phalanx of lawyers and character witnesses, including New York writers, who testified to what a prince of a guy he was," Fountain says. "And one of the witnesses, who was ostensibly a prosecution witness, was Giants manager John McGraw, who was a curious witness for the prosecution, because he was on record as saying that, 'I don’t think Hal Chase is guilty. And, in fact, if he’s proven innocent, I would welcome him on the Giants in 1919.'"

Sounds a little self-serving, doesn’t it?

"And sure enough, Hal Chase was found not guilty of that, and, in spring training, 1919, he was with the Giants," Fountain says.

'Indict Hal Chase Anyway'

John McGraw’s defense of Chase had it that "Prince Hal" was a fun-loving practical joker who just liked to stir things up. But by that stint with the Giants, even McGraw couldn’t keep Chase in line. He spent the last part of the season on the bench, probably less for bad play than for suspicious play. And though he was out of the big leagues by then, when the Black Sox went on trial for tossing the 1919 World Series to the Reds under the direction of various professional gamblers and gangsters, Chase’s name came up, despite the lack of any evidence against him.

"I think the sense was that, 'Look, let’s indict Hal Chase anyway,'" Fountain says. "'He’s gotta be guilty of something. If he’s not involved in this, he’s gotta be involved in something else, and maybe we can bring him in and testify, and maybe we can get to the bottom of this.'"

"I thought the reasoning was, 'If there’s a fix in baseball in 1919, Hal Chase has gotta be involved, somehow," I say.

"Well, I think that that was his stature — that he was the Babe Ruth of ballgame fixers," Fountain says.

Chase was subpoenaed. "Let 'em extradite me," he said, and the court in Chicago never did. So Chase kept playing baseball in various so-called "outlaw leagues," where the players jumped — sometimes midseason — to whichever club offered them the most attractive salary. In that context, Prince Hal’s modus operandi remained the same, even when he had nothing to gain. Following one particularly suspicious performance ...

"A writer came up to him afterward and said, 'You were trying to lose that game today, weren’t you?'" Fountain says. "And he said, 'Yes, I was.' And he says, 'Why?' And he says, 'Well, you know, this guy from Lordsburg' — and he referenced one of the local gamblers — 'He came up to me before the game and asked me if I wouldn’t help him out, because he had money on the other team. And he’s a nice guy, so I said, "Well, why not?"' He was kind to strangers."

Chase played in outlaw or semi-pro leagues for another decade or so. Eventually drinking ruined his health, and according to an article published on Chase by the Society for American Baseball Research, "his last 15 years were miserable." He lived on the charity of his sister and her husband, who resented the imposition.

Interviewed in the '40s, Chase acknowledged that he had been involved with gamblers throughout his career, though Charles Fountain won’t go quite so far as to say Prince Hal repented.

"It wasn’t exactly that he expressed remorse or sorrow for what he did, but he was perhaps wondering what might have been," Fountain says. "'Was I really as good as everyone told me I was, and that I believed that I was? And what might I have been had I taken a different path?'"

Read more about Hal Chase and the players who were actually involved in the Black Sox scandal in Charles Fountain's book, "The Betrayal."

This segment aired on October 28, 2017.