Advertisement

Veterans Day Show

1942 Rose Bowl Rivals Reconnect During WWII

Resume

This story originally aired on Dec. 3, 2017. This week it appears again as part of our Veterans Day show.

The first thing Charles Haynes and Frank Parker had in common was that they played in the same football game.

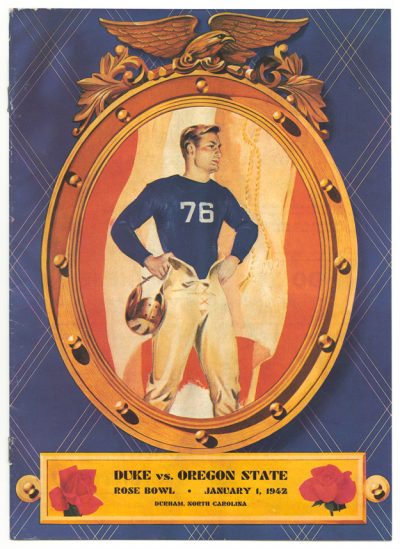

For a couple of reasons, it was an unusual game. It was canceled, argued about, then un-canceled and then relocated.

The game customarily took place on New Year’s Day in Pasadena, California. But not in January of 1942. That was because on Dec. 7, 1941, the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor. Pasadena was close enough to Hawaii to arouse concern.

"About six days after Pearl Harbor, Lt. General John DeWitt, who was in charge of the Fourth Army on the West Coast, based in the Presidio in San Francisco, made the determination that the Rose Bowl Game should not be played — that if that many people were in the same spot, the Japanese bombers were likely to target it and the Rose Parade. So, he asked the governor of California to call off the game, which he did," says Brian Curtis, who has studied and written about the events of that time, among them the debate over the fate of the 1942 Rose Bowl Game.

A Transplanted Game

"Many in America were split," Curtis explains. "And the newspapers nationally weighed in. There were editorials stating that 'We are now a country at war. Our young boys are going off to fight. The last thing we should be thinking of is playing some silly football game.' Then there were other newspapers and Americans that weighed in and said, 'Wait a minute. If we stop playing our games, if we stop living our lives, then the Japanese have beat us, even though they only attacked us in Pearl Harbor in Hawaii.'"

The latter point of view won out.

The 1942 Rose Bowl Game was played, but it was relocated to Durham, North Carolina, home of Duke University. Oregon State would play Duke because, as the winners of the Pacific Coast Conference, Oregon State had earned the right to pick their opponent. They chose Duke, the team generally regarded to be the nation’s strongest that season.

Oregon State graciously agreed to travel across the country for the game. Duke’s roster included Charles Haynes, a local boy from Durham.

"Charles was a good student, a great wrestler, an OK football player, a boy scout, an eagle scout, whose father worked for the American Tobacco Company in Durham, as tobacco at that point was still at the center of life in Durham and much of North Carolina," Curtis says. "He matriculated to Duke and played on the football team for Coach Wallace Wade. Often found himself as more as a cheerleader from the sidelines as opposed to playing."

Among those determined to upset Haynes and his highly regarded teammates was Frank Parker, an imposing Oregon State guard.

"Frank Parker couldn’t have been farther away, literally and figuratively, from Charles Haynes," Curtis says. "Parker was a very poor boy, whose father died running bootleg liquor on Christmas Day when he was just 12 years old. At the age of 13 or 14, he was helping to pick up trash and drive dump trucks with his step-father, who actually was his uncle, but that’s another long story. And he was smart enough and good enough and strong enough to go to Oregon State University and start studying agriculture."

Charles Haynes, the son of a wealthy tobacco merchant, may or may not have had any contact with Frank Parker, son of a dead bootlegger, before, during or after that transplanted football game, in which Oregon State upset Duke before an estimated 50,000 spectators.

Familiar Faces And A Life Saved

Shortly, thereafter Haynes and Parker had something else in common: They were both in the Army. Haynes was turned down the first time he tried to enlist. He had to memorize the eye chart to pass the physical.

Parker also enlisted, and during what must have seemed an interminable delay, he was shipped from base to base within the U.S.

By the early summer of 1944, Haynes was in Italy, fighting for territory, hill by hill, yard by yard. And that’s where he crossed paths once again with his former Rose Bowl opponent.

"In July of 1944, Frank Parker finally came over to Italy as a replacement soldier," Curtis says. "And within a day or two of his arrival, they met. Frank was very shy and quiet, contrary to his large, behemoth size. Charles Haynes was always willing to strike up a conversation, and he did with Parker. And very quickly they realized their connection — that they had both played in this remarkably transplanted Rose Bowl Game, at that point 2.5 years earlier. So they became friendly. They were stationed, obviously, in the same division, almost in the same platoon. So they often were fighting side by side in action."

On a day when the two former rivals were not side by side, Charles Haynes led his company up a hill he’d thought was quiet. He was surprised by a German artillery attack.

"So he was wounded, had wounds in his chest the size of a fist, wounds in his leg," Curtis says. "It started to rain. It was too dangerous for his fellow soldiers to rescue him. So for 17 hours, Haynes thought he was dying, coming in and out of consciousness.

"Word had gotten back to Frank Parker, who was at another part of the fight, that Haynes had been wounded. And it was Parker and another soldier that made their way up to the top of this ridge. Haynes was conscious at the time. He recognized Parker. Parker and this other soldier were able to carry Haynes, under fire, down a hill to a medical aid station."

Parker returned to battle immediately after the rescue. Haynes spent several months in hospital, then returned to his unit.

Taking Different Paths After The War

When the war ended, Haynes took up the life of a wealthy young man in Durham once again. He ran a construction business. He opened up a restaurant. He was apparently able to leave behind the horrors of battle.

The man who saved his life was not so fortunate.

"Frank Parker suffered, like many veterans did," Curtis says. "In fact, he stayed over in Europe an extra year or so when he didn’t have to, because he was so worried that he had changed fundamentally as a person, as a human, as a Christian, that he was not the same person that his wife, Peggy, had married."

Haynes, gregarious after the war as well as before it, thrived in business and in his personal life. He told people about Frank Parker and the exceptional coincidence that had found his former opponent on the football field saving his life on a muddy hill in Italy.

"Charles Haynes embraced Frank Parker, gave him a hug, told everyone at the reunion, kept pointing out, that this was the man who saved his life."

Brian Curtis

Parker eventually returned to Oregon. He rarely told his family anything about what he’d seen and done during the war, and he found adjustment to civilian life as hard as he’d feared it might be.

"I think even his children understood at an early age that dad had issues and at times would disappear into a bar for a day or two," Curtis says. "Never hurt his kids, never hurt his family — you know, got into fishing and would disappear for months on end."

Parker apparently felt that absence would spare his family embarrassment and shame.

"And it really wasn’t until he was about to attempt suicide after his wife’s passing, well into his 70s, that he finally went to a VA and was hospitalized for a couple months," Curtis says.

Opponents, Comrades Reunited

During the years after the war, Haynes and Parker wrote each other a few times.

Duke hosted a reunion for both teams from the '42 Rose Bowl, but Frank Parker didn’t make the trip from Oregon.

So Haynes — restaurateur and businessman — and Parker — disappointed fisherman — didn’t see each other until October 1991, when Oregon State hosted a 50th reunion gathering for the veterans of the only Rose Bowl Game ever to have transpired outside of Pasadena. Haynes was determined to get to that second grand occasion.

"Charles Haynes made the effort to cross the country solely to be able to see Frank Parker and thank him," Curtis says. "Charles Haynes embraced Frank Parker, gave him a hug, told everyone at the reunion, kept pointing out that this was the man who saved his life. As they read the names of deceased players for Oregon State and Duke, Haynes started to cry and looked across the room at Parker."

Parker presented Haynes with a money clip carved from a whale’s tooth — a souvenir of the months Parker had spent at sea as a fisherman.

Haynes was the beneficiary of Parker’s exceptional courage, and Parker was a hero. “Hero” is a word too often applied to football players and other athletes who save nobody. But though Frank Parker saved Charles Haynes, he couldn’t rescue himself from the consequences of the terrible personal damage he suffered during the war.

The unraveling of Parker’s life after the war is something Brian Curtis feels shouldn’t be forgotten.

"We think of this generation as the greatest generation, for their heroism, which is absolutely true. What we don’t hear a lot about is the homelessness, the divorce, the alcohol, the lack of mental health care that many of these gentlemen got," Curtis says. "Frank Parker suffered like many veterans did — never fully came to grips of the man he became."

Charles Haynes suffered a heart attack and died in 1994, just three years after the reunion in Oregon. Frank Parker was eventually diagnosed with PTSD and depression. He died in a nursing home in 2002.

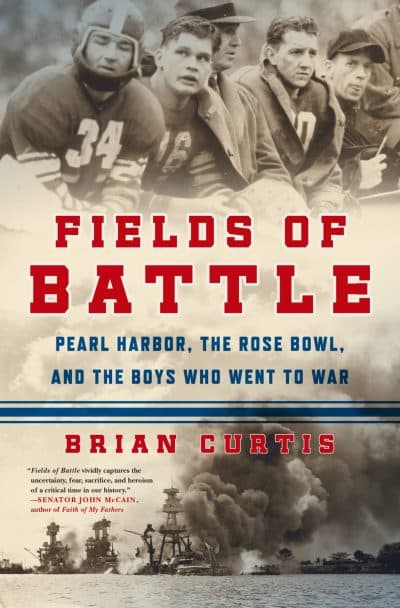

In his book, "Fields of Battle: Pearl Harbor, the Rose Bowl, and the Boys Who Went to War", Brian Curtis explores at greater length the lives of Charles Haynes, Frank Parker and some of the other young men who went directly from the football field to the war in Europe.

This segment aired on November 9, 2017.