Advertisement

Baltimore And The Colts — A Bond 'You're Never Gonna See Again,' Upton Bell Says

Dallas loves the Cowboys. Pittsburgh loves the Steelers. Lots of other NFL cities feature fans who spend more than reason could dictate on season tickets, paint their faces in team colors and sit in freezing weather, howling like dogs ... because some people in Cleveland still love the 0-16 Browns.

But where are the roots of the love between a pro football team and the town where it lives?

'In A Family'

Upton Bell thinks he knows. He started learning the answer 57 years ago.

"And you were how old?" I ask him.

"Twenty-two, going on 10," he says with a laugh. "It was a summer job, but with the idea that the following year, when I finish college — which I didn’t — that I would come back, and I would have a full-time job with the Colts."

Upton Bell is the son of Bert Bell, who was the commissioner of the NFL from 1945 until his death in 1959, so a summer job as a gofer in the league was natural enough for young Upton.

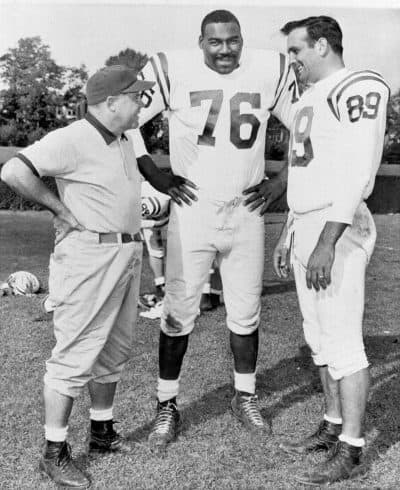

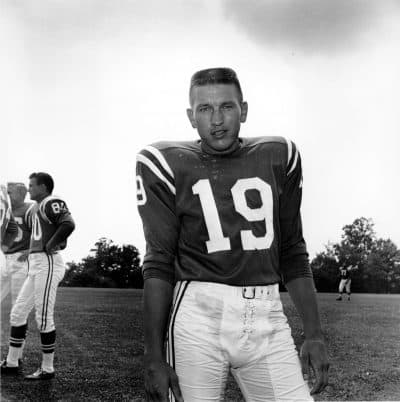

Upton Bell feels he was especially fortunate that his first employer was the Colts. He began feeling that way when he entered the team’s training camp locker room for the first time to encounter quarterback Johnny Unitas, star receiver Raymond Berry and defensive standout Gene "Big Daddy" Lipscomb, among others.

"Every one of them walked over: 'Hiya, kid. Your father was great. Welcome to the Colts. What can we do for you?' " Bell recalls. "Can you imagine getting that today? It was like I was almost — already, in the first few minutes — in a family."

According to Ron Borges, who covered the Colts for a time, even fans without Bell’s entre felt that way about the team in those days.

"Johnny Unitas ran an acetylene torch at the Bethlehem Steel plant in the mornings," Borges says. "Artie Donovan was a liquor salesman. A lot of these guys, they had to work, and then they would go to their other job, which happened to be football."

Advertisement

Overcoming The 'Great Inferiority Complex'

So fans of the Colts could identify with the players, and the players were good with that. Borges says that at training camp, there were no ropes between Unitas and the working stiffs who came to see him. Beyond that, those Colts were good. They’d won championships in 1958 and 1959 for a town that needed a champion.

"Baltimore has the great inferiority complex," Borges says. "They’re trapped between New York and Washington. There’s no VIP room in Baltimore. Most cities, you got a VIP room for the athletes and the politicians. And in Baltimore, you went to Gussie's --"

"Gussie's Downbeat," Bell interjects.

"Gussie's Downbeat, and it was just as likely you were gonna run into Gino [Marchetti] and Unitas and those guys as you would run into me and Upton," Borges continues. "And I think Unitas set the tone. Unitas was about as down-to-earth a guy as you were ever gonna find in professional sports."

The accessibility of the players — Johnny Unitas in particular — bred familiarity, or at least the powerful illusion of familiarity. As Borges puts it, the city of Baltimore embraced the Colts the way a small community sometimes embraces a high school team that wins a state championship.

Bell feels as if those players who stayed around after they retired helped establish and reinforce the relationship between the team and the community, a relationship that the active players also enjoyed.

"It was like watching an old movie of the guy that works in the shipyard, comes in, he has a shot and a beer, and he’s talking to his buddy: 'Oh, I gotta go home. I’ve gotta pay the bills,' " Bell says. "They might end up sitting next to one of the players, and the player’s saying, 'Oh, my god, I got hurt today. I can’t stand the coach. He’s a pain in the neck.' And you’re never gonna get that again."

'Baltimore Is Still Here In This Stadium'

Nope, you’re probably not. Most of the players in today’s NFL don’t have to learn welding or drive a beer truck in the offseason. They may sign autographs at training camp, but they aren’t ordering burgers with the fans when day is done. Such was already the case 33 years ago, when the team Upton Bell recalls with such affection left town. That fact was indisputable. The team became the Indianapolis Colts, and the owner, Robert Irsay, became the most hated man in Baltimore.

But it was a testament to the connection between team and city that numbers of citizens refused to acknowledge what had happened. The Baltimore Colts marching band did not disband. They played on, as if there was still a home team for which to play. And, as Borges recalls, the band members weren’t the only ones in Baltimore to firmly reject rejection.

"I don’t want it to come back. Because I had it, and a few other people had it. You’re never gonna see it again."

Upton Bell on the relationship between Baltimore and the Colts

"That fall, when what would have been the opening game of the season at Memorial Stadium, the band was there, even though the team was not, and one other person was," Borges says. "John Steadman was the leading columnist in town, who sat in the bleachers for four quarters and then wrote a column. 'There's no team here, but we’re here. Baltimore is still here in this stadium.' And they fought and fought and fought to get a team back, and ultimately, in true American fashion of the 2000s, they stole somebody else’s team and got it back."

Cleveland’s. They stole Cleveland’s team. Or maybe the people of Baltimore were just receiving stolen goods. Doesn’t matter. Or at least in one sense, it doesn’t matter to Upton Bell. Sure, he says, the Ravens won the Super Bowl in Baltimore. But no team’s ever going to capture the hearts of the people there the way the Colts did back in the late '50s and early '60s. And maybe Bell is right. But by building that powerful bond between team and community, the Colts became the envy of every other team in the league, and they gave the Cowboys, the Patriots, the Steelers et al. something to which they could aspire: brand loyalty built on something more human than mere “brand.”

But would Upton Bell want to see the return of those days when the players were without entourages? When they lived down the street from the plumbers and the grocery clerks rather than in gated communities with the movie stars?

"I don’t want it to come back," Bell says. "Because I had it, and a few other people had it. You’re never gonna see it again."

Maybe not. But what we do see every weekend — and on Monday and Thursday nights as well, and on a couple of Saturdays, once the playoffs begin — is the contemporary version of what those Colts created in Baltimore: loud enthusiasm, bordering on hysteria, for whoever’s wearing the home team’s jersey.

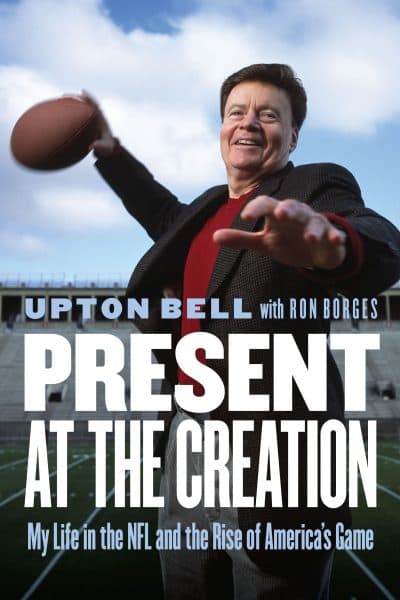

Read more about the Baltimore Colts of the 60s in Upton Bell’s new book, written with Ron Borges, "Present at the Creation: My Life in the NFL and the Rise of America’s Game."

This segment aired on January 6, 2018.