Advertisement

The Controversial History Of Headgear In Girls' Lacrosse

John Hulbert is a dad and a coach. First, it was soccer and baseball. A while back, John and his family moved to Florida. That’s when John’s son decided he wanted to play lacrosse.

"And next thing you know, I became a lacrosse parent," Hulbert says.

Every time he played, Hulbert's son would put on gloves, elbow pads, arm pads, shoulder pads and a helmet. But when Hulbert's daughter started playing the game, something was different.

"They only wore goggles," Hulbert says. "That's all they wore — goggles and a stick and cleats — and that's all they were required to have."

Boys’ lacrosse is a contact sport. In the girl’s game, stick-to-stick contact is the only contact that’s allowed.

But Hulbert grew up playing ice hockey. He knows that, sometimes, things happen.

"I've always had a helmet and full face mask. And some of the worst times I've ever been hit is always by accident," Hulbert says.

Hulbert is now the head girls’ lacrosse coach at Estero High School in southwest Florida. Last year, for the first time, high school girls in Florida were required to wear specially designed girls’ lacrosse headgear. It was a move that Hulbert welcomed.

"The ladies are getting bigger, faster and stronger," Hulbert says. "The game is getting better. It's developing. They're shooting balls, you know, anywhere from 35 to 55 miles an hour. The way the play is going, you know, I want my players — I want my daughter — to be as protected as she can."

But John Hulbert knows that the question of helmets in women’s lacrosse is anything but simple. The controversy surrounding this issue runs deep.

"It's like the Hatfields and the McCoys," he says.

More Protection = More Risks?

It might not make a lot of sense at first. What could be wrong with helmets? After all, the more we learn about concussions and the long-term effects of brain injury, the more reasons we have to worry.

But here’s the thing: Those who are arguing against the use of helmets are doing so because they also want to keep players safe. And they know about the studies that show that wearing more protective equipment in sports leads to a higher level of aggressive play.

"And we know, we know, we know, we know from science that helmets will not prevent concussion," says Nancy Burke, a retired athletic trainer who specializes in injury avoidance.

Advertisement

This claim she’s making — that helmets don’t prevent concussions — a lot of other doctors and experts have told me the same thing.

Burke compares the brain to the yolk of a raw egg inside the shell. Shake the egg, and the shell remains intact. But you can feel the yolk banging against the inside of the shell.

"No helmet is going to stop that," Burke says. "It just isn't."

All of this has left people like Rose Marie Marinace wondering who — and what — to believe.

Marinace is a teacher and a high school girls’ lacrosse coach in New Hampshire.

"I really like the game the way it is," Marinace says. "But if I'm going to be a responsible coach, I have to know what's true instead of just go with my biases."

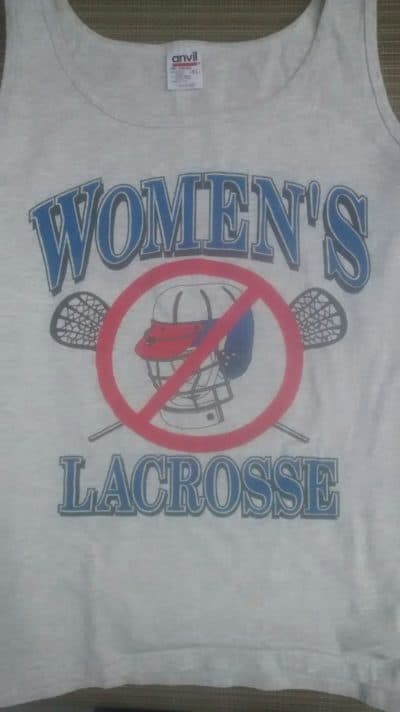

Last season, one of the towns in Marinace's division required all of its players to wear the new, specially designed women’s lacrosse headgear. (US Lacrosse avoids using the word "helmet" for reasons that will become clear later.)

"I've had teams where one or two girls will wear headgear because their parents wanted them to, but we've never faced a team where the entire team was wearing headgear," Marinace says.

Marinace didn’t want to name the team, because she says they didn’t do anything wrong. There was no unsportsmanlike behavior. No unusual aggression.

But Marinace missed a lot of what was happening on the field in that game, because she was busy attending to the only major injury her players suffered all season: a broken elbow.

"The girls were the ones sensing that, physically, the other players were just too close and just felt just a little too safe coming close — with their sticks, with their bodies — and that it just changed the nature of their space on the field," Marinace says.

And this is the big fear when adding head protection to girls’ lacrosse. Or any sport, really. Will adding more protection make players feel like they’re more protected? Will they then take more risks? Will there be more injuries?

Rose Marie Marinace is looking for proof — some sort of scientific data comparing girls in Florida who are required to wear the new headgear to girls everywhere else who are not.

"Headgear didn't seem to prevent boys from getting concussions, so what's the result with girls?" Marinace asks. "If I'm going to be a responsible coach, I definitely want the answer to that question."

I’m just going to be upfront about this: I’ve spent almost a year looking into this story, and I don’t have an answer to that question — yet.

But I can answer some other questions. Like, what happened to make so many women’s lacrosse coaches so skeptical about protective headgear? And why might what’s happening today be different from what happened then?

Two Sports, One Name

Before we get to that story, we need to establish one thing. And that’s that boys and girls do not play the same game.

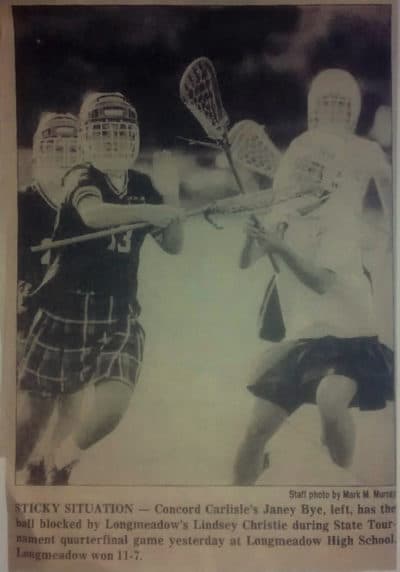

"There is nothing similar except for the lacrosse ball and the name," says Kathy Tomassetti. She officiates in Western Massachusetts and was the longtime girls' lacrosse coach at Longmeadow High School. "There's not one rule the same. The field is different. The number of players on the field is different. There's just no similarities. They have the same name, and that's all I can tell you."

How did we get here: two sports, one name? Well, lacrosse was originally a Native American sport played by men. It was sometimes called "the Little Brother of War."

"And the story is that Queen Victoria, at some point when she was visiting Canada, saw this game and thought it was a marvelous game and introduced it to women in England," says Susan Ford, a longtime coach and official and the president of the US Women’s Lacrosse Association from 1995 to 1997.

Women’s lacrosse developed into a free-flowing game of keep-away with very few rules and no strict boundaries. By the time coaches from England brought the sport back to North America, the emphasis was on fast breaks, skilled passing and catching, and …

"Staying reasonably within the definition of what we would call now ‘field space,’ " Ford says.

If the game’s played in that spirit, Ford says, players don’t come into contact with each other — and they shouldn’t come into contact with the ball or sticks, either.

And there’s something deeper going on here. Because women like Ford aren’t just committed to keeping the players safe. They also want to protect and preserve the unique nature of the women’s game.

"This is a game that belongs to us," Ford says. "We've nurtured it. We've taken responsibility for it. And we want to keep it this way."

"This is a game that belongs to us. We've nurtured it, we've taken responsibility for it. And we want to keep it this way."

Susan Ford

But back in the 1980s, something happened in Massachusetts that threatened all of that.

"The court case, as I remember it, it was brought by a family whose daughter had been hit in the eye with a ball," Ford says.

To avoid a lawsuit, the Massachusetts Interscholastic Athletic Association, or MIAA, held a meeting and decided that high school girls' lacrosse players would be required to wear helmets.

"It was a gut punch, you know — it really was," Ford says. "To take responsibility away from the people who knew the game best and give it to people who had no idea of the history of the context of the game was just palpably unfair. And I think all of us left that room really dejected."

To make matters worse, lacrosse helmets that would fit high school girls weren’t available. So the MIAA decided the girls would wear youth ice hockey helmets.

"You put a helmet like that on a young girl, and when she turns to the right or the left, she sees to the side of the helmet," Ford says.

"A lot of them didn't fit properly, because they didn't buy new ones. They just used the what they currently had," former Longmeadow coach Kathy Tomassetti says. "The recklessness happened right away. Everybody just thought she was protected, so they just swung crazily. And there were plenty of head checks that weren't even called because it didn't hurt them, is what the officials were saying."

"I think things just got sloppier," Ford says.

After a few years, Tomassetti took a break from coaching. And when she came back, she had a mission.

"My goal was to get the helmets off the heads," Tomassetti says. "It was so bad."

'Take Them Off'

In 1995, almost a decade after the MIAA put girls’ lacrosse players in helmets, Tomassetti sent a survey to each of the 16 public high school girls’ lacrosse coaches in the state asking if they were for or against helmets in girls’ lacrosse.

"Actually, I sent 'em a little postcard in the mail inside a No. 10 envelope," Tomassetti says. "It was the old-fashioned way."

"And they said, ‘Take them off,’ " Ford says. "It was a unanimous reply from every single one of them."

But it was going to take more than a postcard survey to convince the MIAA. That’s where athletic trainer Nancy Burke comes back into the story. At the time, she was heading up the safety committee for US Women’s Lacrosse, and she’d been asked to study the injuries that were happening in the sport.

"Quickly, it became apparent that the injuries were not to the head as much as the injuries were to the nose and to the orbital bone — and, in some cases, a fracture to small, very thin bones that support the eyeball," Burke says. "And these are serious injuries. There’s no question about it."

Burke believed that what the sport really needed was eyewear. But there was nothing appropriate on the market.

And then one day, Burke was having lunch with a representative from an equipment manufacturer.

"I drew something out on a napkin, which was a version of a very shortened catcher's mask and asked, ‘Do you think you could do this?’ " Burke remembers.

A while later, Burke had a working model. But it wasn’t easy convincing college coaches to test it out. She showed up at an annual coaches' conference with a slideshow of graphic photos of the injuries girls were suffering — injuries she believed the eyewear would protect against. By the time she was done, 10 college coaches agreed to participate in the trials.

A Compelling Case

Five teams wore the eyewear. Five teams did not. And the results were promising.

"Orbital injury, head-and-face, nasal injury dropped to just about nothing with protective eyewear," Burke says.

But even more important was what those coaches told their colleagues at the next annual conference.

"They stood up and said, ‘This did not change the game,’ " Burke says. "That was huge."

It was during this time that Nancy Burke got a call from Kathy Tomassetti, asking for help.

Burke flew to Massachusetts to show the MIAA the data she had collected. She was nervous about how the board would react. But she didn’t need to be.

"They wanted to do the best by their student athletes," Burke says.

The board had heard that helmets were changing the game — that college coaches weren’t recruiting girls from Massachusetts because they didn’t want to have to break them of bad habits.

So when Burke presented them with evidence that eyewear was a better solution, the board listened.

Burke flew back to D.C. Later that night, she got a call from Tomassetti. The MIAA had voted to remove the mandatory helmet rule. Instead, girls would be required to wear eyewear.

Tomassetti was "beyond the moon" over the news, Burke says. "She was over the moon, and the other coaches were, too."

"Everybody was looking around and saying, ‘Well, let's not ever let that happen again.’ " Ford says. "You know, ‘Let's be sure that any equipment that's introduced meets a certain standard to protect the integrity of the game.’ "

Protecting The Integrity Of The Game

Over time, what had happened in Massachusetts became a cautionary tale. And the myth surrounding it kept growing. And it kept giving lacrosse coaches another reason to resist equipment changes in the sport.

In 1998, the governing bodies for the men’s and women’s games merged, coming under the umbrella of US Lacrosse.

And about a decade later, when concussions started to become part of the national conversation, Ann Kitt Carpenetti at US Lacrosse took another look at the data comparing the injury rates of lacrosse to other sports.

"And so the studies were showing us that our rates of concussion were, I think, in the rankings, you know, fourth or fifth for women," Carpenetti says. "We weren't the No. 1, but we weren't No. 10, either."

No matter how many changes US Lacrosse made to the rules and to training for coaches and officials to make the game safer, there were always those who would drive past a lacrosse field and say, "Helmets are good enough for the boys’ game. Why aren’t girls wearing them, too?"

But still, whenever the organization floated the idea of headgear, there was a large contingent of coaches — especially in college — who would remember what happened in Massachusetts and say, "Not again."

"For me, it was, like, the enigma," Carpenetti says. "Like, I kept hearing about what happened in 1986. What I'd heard was, ‘Oh, it just got so violent. They just decided it was safer for the players to take them off.’ I'm like, ‘I need to see what this looks like.’ I actually got a copy of a video — I think a state championship game that someone sent me.

"And it just ... I didn't see any of that kind of physicality that in my mind I was expecting to see, like girls just swinging at each other's heads. That wasn't it at all."

Creating The Standard

In 2010, US Lacrosse decided that it was time to develop a standard for head protection that would mitigate stick and ball impacts in the women’s game. No, it would not stop concussions. But maybe it would help.

The organization knew that this time, they needed to get it right. So they made sure that everyone had a seat at the table, from researchers who knew the latest injury data to people who had fought against the use of ice hockey helmets in Massachusetts.

"I went to those meetings. I listened to the manufacturers. I listened to the doctors," Susan Ford says. "They were very, very clear on what the women's game was all about and why we wanted to do the best for the players on the field. And the standard took a while to get to where everybody felt comfortable with it."

The headgear (US Lacrosse is still careful not to call a helmet) came on the market in spring of 2017. (And I have to say, it looks a lot like a helmet to me.)

For most players, wearing the headgear is still optional. And while the design worked well in the lab, US Lacrosse is currently funding a study to address the bigger questions: Does the headgear reduce concussions? Are players more likely to suffer other injuries because they’re taking more risks? And does the headgear change the character of the game?

Those answers aren’t ready — yet. But Ann Kitt Carpenetti says she hopes to have some data to share by August.

This segment aired on May 11, 2019.