Advertisement

The Man Behind Joe Frazier's Mean Left Hook

Resume

The rivalry between Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali went far outside the boxing ring. Just days before their second fight, 1974’s Ali–Frazier II, the heavyweights met at ABC’s New York television studios for an interview with Howard Cosell.

"That shows how dumb you are," Ali said to Frazier. "That shows how dumb you are."

Ali called Frazier "ignorant." Joe Frazier rose from his chair and threatened the seated Ali. Their handlers tried to intervene, but soon the two were wrestling on the floor while horrified stagehands looked on. It was not a hoax.

At other times, Ali called Frazier a "savage" and an "Uncle Tom." Ali’s act was seen by many as entertaining theater and good boxing promotion. But it hurt Frazier. Because much of what people thought they knew about him wasn’t true.

No Future In Beaufort

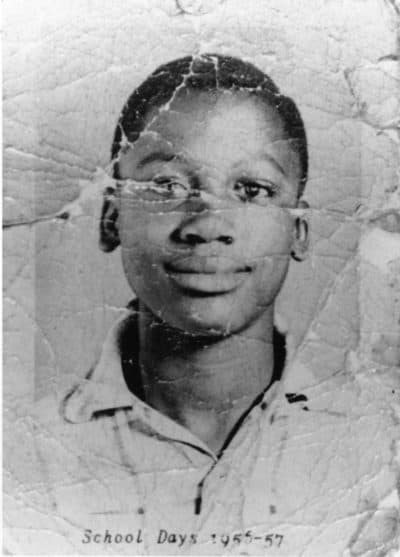

Joe Frazier was born in 1944 in Beaufort, South Carolina. He was one of 12 children. His father was a bootlegger.

"His mother picked vegetables in the fields, as did many other members of his family," writer Mark Kram Jr. says. "He grew up in a house that was more or less a shack. He grew up amid malnutrition, disease and, essentially, the enslavement of the Jim Crow laws.

"You couldn't look a white man or a white woman — and particularly a white woman — in the eye, for fear of retribution. He said that Beaufort never got tired of reminding you that you were the 'N-word.' "

But Frazier’s mother had a rule.

"Dolly would not stand for anything said about white people," Kram says. "You know, if her kids made some sort of offhanded remark, she'd slap them down. She wouldn't stand for it."

But that didn’t mean Frazier suffered abuse easily. Once, when Frazier was in his teens, he was working at a farm in Beaufort. When a white foreman threatened to take a belt to another young African American, Frazier stopped him. He just couldn’t stand watching others being pushed around.

"And that's fundamental to his nature," Kram says.

In 1959, Frazier saw no future in Beaufort outside of working in the fields and helping his father run the family still. So he hopped on a Greyhound bus headed for New York City, where he joined members of his extended family. He was just 15. But there wasn’t much of a future in New York City, either.

"He found it hard to find work," Kram says. "And to supplement what little money he had, he and a friend would steal cars and sell them to junkyards.

"There was a sense among his family that, if he stayed in New York, it wouldn't be a positive outcome for him. So they sent him down to Philadelphia to live with his sister, Mazie. She sat down with Joe and she said, 'Look, if you get into trouble down here, there's nothing I can do for you.' "

Mazie suggested that Joe join the Police Athletic League. At least he’d be safe in a gym filled with cops.

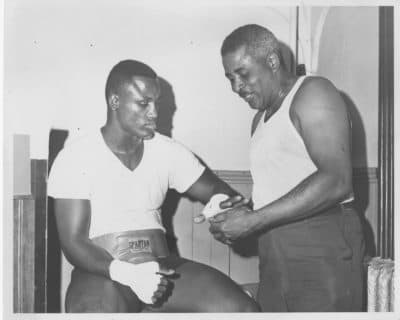

"So he went over to the gym," Kram says. "And when he hit the heavy bag, it made such a resounding 'crack' that you could hear it across the street."

War Of Words With Ali

Over the next few years, Frazier rose quickly up the boxing ranks. He won gold at the 1964 Olympics. In 1968, he captured the New York Athletic Commission heavyweight title, which marked the beginning of a long championship run.

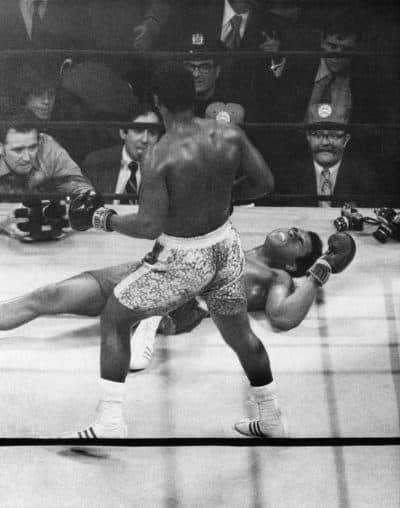

In 1971, Frazier fought Muhammad Ali in what was billed as the “Fight of the Century” at Madison Square Garden. In the lead up to the fight, Ali intensified his attacks on Frazier, saying he was too dumb and ugly to be champ, and calling him an “Uncle Tom” for working with white trainers. It was the biggest sporting event of the year.

Frazier won by unanimous decision and became a celebrity. Politicians wanted to see and be seen with him.

On April 7, 1971, just one month after his win over Ali, Frazier became the first African American man to speak before the state legislature in Columbia, South Carolina.

"It was an extraordinary event," Kram Jr. says. "He reached out and tried to implore the members of that assembly to be open to bringing the races together. And, indeed, he wanted to."

Frazier told the legislature that not much had changed since he left Beaufort, about 140 miles south of the state capital.

"We must save our people, and when I say our people, I mean white and black," Frazier said in his address. "We need to quit thinking who's living next door, who's driving a big car, who's my little daughter going to play with, who is she going to sit next to in school."

"Publicly, they were all for it," Kram says. "The governor was behind him. The politicians shook his hand. They were thrilled to have him. He was the champ."

After his address to the state legislature, Frazier sent a representative to Beaufort to propose the building of a public playground that he would pay for himself. But when officials learned that Frazier wanted the playground be open to black children and white children, with one water fountain for all of them ...

"He was slapped down," Kram says.

When news reached Frazier in Philadelphia that Beaufort officials wouldn’t agree to his terms ...

"Joe said, 'Forget it, then,' " Kram says. "Because he wasn't going to be a party to furthering the separatism. It bothered Joe. That's not what Joe was about."

While Frazier was losing this private battle, Ali continued attacking him in public.

In May of 1971, Frazier took a portion of his $2.5 million "Fight of the Century" purse and purchased the Brewton Plantation in Beaufort.

"His family, generations back, had been enslaved in places of this sort," Kram says. "And now he was the owner of one. The symbolism shouts at you."

Frazier’s mother lived at Brewton Plantation along with other family members. Frazier continued to live in Philly.

"He basically kept his ties to Beaufort," Kram says. "In fact, all during his life, he was connected to Beaufort."

'You Need Help, Man'

Joe Frazier’s boxing career ended in 1981. He continued to run his boxing gym.

"He was available," Kram says. "You didn't need to make an appointment to find Joe Frazier in Philadelphia. All you had to do was walk up to the gym on North Broad Street, walk in, and he would have genuine time for you.

"He performed all these acts of generosity the public never really knew about or found out about. He would see a motorist stranded on the side of the road with a flat tire. And he would pull over, get out of his car, get the jack out of the trunk and fix the tire.

"He did this not just once, but again and again. It was almost if he was his own AAA. And, you know, his friends were driving with him. It became such a commonplace occurrence that they'd say 'Oh, Joe, not again!' He'd say, 'Well, what if it was your mother that was stranded there?' "

"In a sport that many think is inhumane, Joe had a great humanity."

Mark Kram Jr.

On a cold December day in 1986, Frazier was driving in Philadelphia with his son and another boxer. He spotted a legless man in a wheelchair trying to cross Broad Street. The man had a can of kerosene in his lap.

"Joe pulled over, stopped in the middle of Broad Street, got out of the car in his fur coat and cowboy hat, picked the guy up and put him in his car [and] drove him home," Kram says.

The only items in the man’s home were a table and chairs, a television, and two kerosene heaters.

"The man's wife couldn't believe that Joe Frazier was standing there in the middle of her living room," Kram says. "And he takes a roll out of his sock and peels off a couple hundred dollars. And the guy says, 'Why are you doing this?' He couldn't believe it. And Joe would say, 'You need help, man.'

"That was his nature. In a sport that many think is inhumane, Joe had a great humanity. He was a good man. Not a perfect man, but a good man."

Frazier's 'Private Voice'

Joe Frazier made many trips back to Beaufort to visit family. Over the years, he noticed that something had changed.

"He would come to town and he was treated very well," Kram says. "Far better than he was when he was even champ."

In 2010, Joe Frazier was presented with the Order of the Palmetto, South Carolina’s highest civilian award. The state that had rejected Frazier’s vision of racial harmony was now honoring him.

Ali tried on many occasions to apologize for his name-calling, but Frazier refused to forgive him. Joe Frazier died in 2011.

What did the boxing world in particular, and the greater world in general, lose?

"Someone who understood that being the champion meant more than just holding a belt in your hand," Kram says. "It meant that you had a voice. And, even if you did not use that voice in the public square, you could use it privately and in ways that helped people along the way. He understood that."

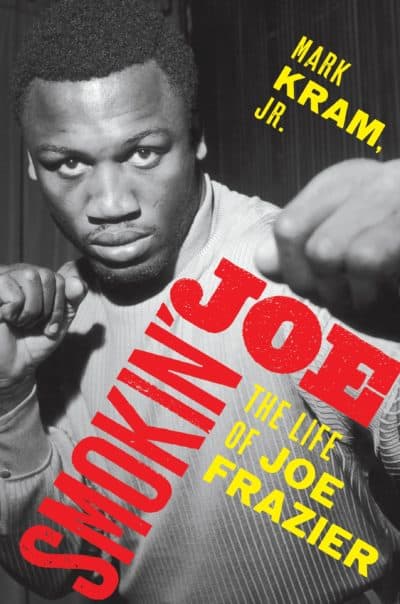

Mark Kram Jr.’s new book is called "Smokin’ Joe: The Life of Joe Frazier."

This segment aired on October 12, 2019.