Advertisement

Peking To Paris: Completing A 10,000-Mile Journey ... 112 Years Later

Resume

The idea came to him in the winter of 2017. Anton Gonnissen was re-reading a book he’d read twice before.

The book follows four teams in 1907 as they race nearly 10,000 miles from Peking to Paris. But five teams had actually started that event.

"There wasn't much written about the fifth competitor, which was Auguste Pons. They sort of left him out in this story," Anton says. "And I thought, like, 'Why did Auguste Pons ... not get his place in history?' Well, it's clear. Because he didn't make it."

And so, as Anton was reading this book for the third time, he had an idea.

"What if," he remembers thinking, "we finish what this guy started?"

'You're Mad'

In a sense, Anton knew what he was getting himself into. The Peking to Paris was brought back in 1997 as an endurance rally for classic and vintage cars. It’s a point-to-point over 36 days. All the competitors stop at the same hotel — or campsite — every night.

Anton and his wife completed the rally six years ago, in the relative comfort of their 1950 Bentley.

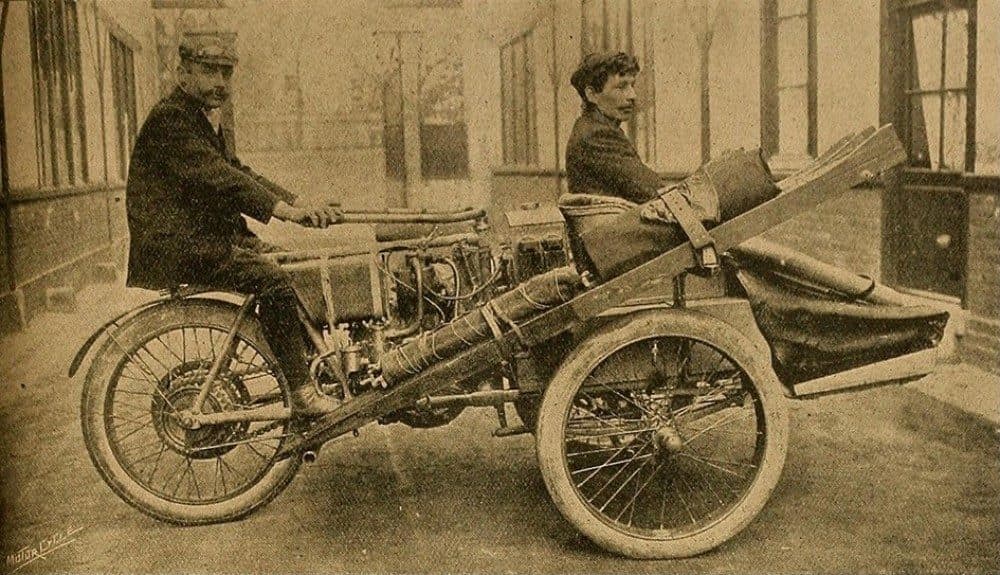

But to “finish what Auguste Pons had started,” Anton would need to complete the journey in a 1906 Contal Mototri.

It’s basically a motorcycle on three wheels, two in the front, one in the back. The co-driver, or navigator, sits between the front wheels in a seat so dangerous the Contal factory gave it a special name:

" 'Le tue Belle-mère,' which means 'the kill your mother in law seat,' " Anton says.

The Peking to Paris is held every three years, and by the time Anton got up the courage to email the race director to ask for an entry, the rally was already full.

"But, since I had a proposal that had never been done before, I was sort of hoping that he would say 'yes,' " Anton says.

The race director got back to Anton a few days later.

"And he said, 'You're mad,' " Anton says.

"Since I had a proposal that had never been done before, I was sort of hoping that he would say yes ... And he said, 'You're mad.' "

Anton Gonnissen

But he accepted Anton’s entry anyway.

"So I — there was no way back from that moment, I think," Anton says.

'No Roads, No Maps ... Uncharted Territory'

The automobile was just over two decades old when the first Peking to Paris race was announced.

"Well, it was a newspaper called 'Le Matin' in France in January 1907," says Tony Jardine, the communications director with HERO/ERA, the company that puts on the modern Peking to Paris rally. "And essentially what they were doing was challenging the automakers of the time to show that modern cars were more than just a novelty for the rich, really."

Forty teams entered, but only five actually made it to the starting line in China.

"No roads, no maps," Tony says. "Uncharted territory."

The route followed telegraph poles all the way from China through Mongolia and Russia.

"So what they decided to do was dispatch mules and camels with fuel into strategic spots, where they could pick up their gas along the route," Tony says.

Without any real roads to rely on, Pons hoped he and his co-driver Oscar Foucauld could just pick up their tiny trike and carry it over obstacles. Still, with just nine horsepower, the Contal was very slow.

"He was the slowest one," Tony says. "But at the same time, I think he was the bravest one. And certainly Oscar, his co-driver, was very, very brave indeed. Because, you know, if you hit any bumps you went over, you would just get ejected straight off the front of it. But I don't think they got that far to find out."

In Search Of A Contal Mototri

If he was to have any chance of finishing what Pons started, Anton Gonnissen first needed to get his hands on a 1906 Contal Mototri.

"I thought in the beginning that I would find one," Anton says. "But that appeared to be extremely difficult. And now I know there must be about four, five or six left in the world."

Where they are is anyone’s guess. Private collectors tend not to advertise vehicles they have no intention of ever selling. Which sent Anton on to Plan B.

"I got a tip, and they said they have one in the storage of the Le Mans 24 Hours Museum," Anton says. "I made an appointment. I spoke to a lot of people, and then I got in. And this was actually quite an important moment, because we were allowed to take all the dimensions. We could measure it up. We took a million pictures."

"And did seeing it make you have any second thoughts?" I ask. "Because I think if I was standing in front of something like that and saw how small and not comfortable it was, I would start thinking 'Maybe I shouldn't do this.' "

"Funny you ask," Anton replies. "Everybody I spoke [to] about this project, they told me to stop it, not to do it. 'It was impossible. I would hurt myself. It couldn't be done. And there was a reason Pons didn't make it.' And, actually, they were all right. And, as the project evolved, I understood more and more what I had to do to get it done."

Attempting Peking To Paris ... 112 Years Later

Since Anton couldn’t find an original 1906 Contal Mototri, he built one using the specifications he had gathered.

And, like Pons had 112 years earlier, Anton made some improvements. He strengthened the chassis. He put on sturdier wheels.

"It also had an engine, 45 horsepower instead of the nine horsepower that Pons had," Anton says. "But, then again, I needed those horsepowers to make it from Peking to Paris on the time that the rally gave me."

While the 1907 competitors could take as long as they needed to get to the next refueling station, Anton would need to make it to the rally stop every night.

But manufacturing a vehicle from scratch took a lot longer than Anton had planned for, and he received his finished 1906 model Contal Mototri with time to do just 150 kilometers — roughly 90 miles — of road testing.

"I thought it was a mistake," Anton says. "But still, as I always say, half the rally is getting to the start."

And so, on June 2, 2019, Anton Gonnissen and his co-driver Herman Gelan lined up at the Great Wall of China near Bejing in a vehicle that had barely been road tested.

"It was raining a little bit, like this drizzle," Anton recalls. "It doesn't make you happy — it drizzles. It's a bit brrr. The flag goes down. You start. People clap. You hear the photographers clickety-clickety away. The mass of people goes open like the Red Sea. You drive through it.

"And one minute later, you're totally alone. There's nobody cheering anymore. There's silence. There's the engine. And you know you're gonna be there for 36 days with a lot of trouble. So it feels amazingly alone when it actually happens, when you drive away."

But when Auguste Pons drove away from the start line in 1907, he felt anything but alone.

From A 'Heart Full Of Hope' To 'Nothing'

"We left Peking on June 10 with a heart full of hope," Pons wrote in an account of the race in August 1907. "All the drivers had a friendship that one might have thought sincere."

"He knew that they would probably be last," Tony Jardine says. "And yet — and yet, in the month they all spent together in the Hotel Peking making all their preparations, they all got on extremely well. And they all made these vows and these promises together that each would help the other out."

But just a week into the race, it all started to go wrong.

"It was the 18th of June that began — what I can call without exaggeration — my ordeal," Pons wrote.

"Pons had got lost from the telegraph poles, and he'd wavered off over to the left, because the track was quite good over on that side," Tony says.

"I continue without worry, thinking to find the telegraph poles a little further," Pons wrote. "After half an hour, no more tracks on the ground, and we had not encountered any path. I was getting very worried, because the gas that I had did not allow me to make an extra trip."

"Then he was very lucky to come across, you know, some Mongolian riders," Tony says. "They’d seen four other vehicles. So they pointed out [a] shortcut for him to get across this grassy section, I don't know, 10, 12 kilometers. And he managed to catch up with the other four vehicles before, you know, he finally got lost again."

"The situation became agonizing," Pons wrote. "Wanting to preserve the petrol that remained to me, I decided to stop next to a camp of Chinese who gave us water."

"By this time, they're already very thirsty, very hungry," Tony says.

"The Chinese water was terrible," Pons wrote. "It was mud. But with what delight we drank it."

"They felt sure that the others, after this time, you know, a day and a half or so, would be looking for them," Tony says. "So they took turns to sleeping and on look out."

The next morning, Pons and Foucauld scanned the horizon, looking for other drivers.

"Nothing," Pons wrote.

'There's Something Strange With Those Front Wheels'

The pair drove on for a few kilometers, before their fuel tank ran dry and they were forced to continue on foot to the next stop.

"Then they marched for something like 6 kilometers, believing it was just over the horizon," Tony says. "It wasn't. They're in a real state. They decide to go back to the motorcycle."

"Stunned by the sun, stupefied by fatigue, tormented by thirst and hunger, we arrive at 7 o’clock in the evening at our motorcycle," Pons wrote. "Without eating, without drinking, we fall asleep with hope again, but a hope that weakened more and more. On the morning of the 20th, nothing, still nothing."

Auguste Pons’ race would end at that spot, in Mongolia.

"Without eating, without drinking, we fall asleep with hope again, but a hope that weakened more and more."

Auguste Pons, August 1907

112 years later, Anton Gonnissen hadn’t even made it out of China when his trouble began.

"After the first day, I looked at the Contal. And I said, 'There's something strange with those front wheels. But anyway, we'll see tomorrow," Anton says.

The next day, when Anton and Herman stopped for fuel, they noticed the front wheels, which were supposed to be straight, cambered in by 10 degrees. The axle had bent almost to the point of failure.

"I showed it to the guy in the petrol station, and he pointed out to a village that was 3 kilometers further, and I understood that he said, 'Ask there,' " Anton says.

'Already Old History'

Anton found the welder and, pointing again at his crooked front wheels, asked him to insert a metal pipe inside the axle to straighten it and make it stronger.

"The way he took the axle off — it was like a surgeon," Anton recalls. "He did it so carefully. And so I was completely reassured. The axle went away with the guy on this small motorcycle. Two hours later, it came back. It was all straight again. So this surgeon puts it back on. Problem solved."

" 'Problem solved,' but you still had a lot of worries in your brain," I say. "A lot of visualizations of what could go wrong if this broke again, right?"

"Something went wrong in my head," Anton says. "So I started to imagine that this axle was going to break while I was on the highway following a truck or with a truck behind me. I mean, I have a very imaginative mind. And then I saw Herman projected out of the seat on the tarmac. And I thought, 'Jesus Christ, this guy's going to die.' So I became a lot more cautious — perhaps too cautious."

"Did you tell Herman that you were having these thoughts?" I ask.

"Nope. Nope. It wouldn't have been smart, I think," he replies.

So Anton kept his worries to himself as he and Herman climbed aboard the Contal for day three — the day they would pass that spot in the desert where Pons ran out of fuel.

"That was an important day — the third day," Anton says. "Everybody started complimenting us. 'Yes, well done.' And, 'You're further than Pons, at least you have this.' But I wasn't satisfied with that result. I didn't come there to get a bit further. I wanted to get to Paris, of course."

By the third day of his ordeal, Auguste Pons had lost all hope of continuing on to Paris as part of the race. But he still had to find a way out of the Gobi Desert. Pons believed the other drivers must have turned around to rescue them by now. But, with no signs of help on its way, he and Foucauld set out again on foot.

"Suddenly, I utter an exclamation of joy," Pons wrote. " 'What is it?' Foucauld asks me. 'Look over there, there. Do you see these tents?' "

"And it was Mongolian tribesmen," Tony says. "And they were saved yet again."

The tribesmen brought oxen to pull the Mototri to the safety of their camp. But Pons couldn’t let go of the fact that it was locals, and not his fellow drivers, who had saved him.

"I think, Karen, you read one the reports that I read when he said, you know, that 'My house,' you know, meaning his whole family house, had put so much into this," Tony says.

"And all this is destroyed by the lack of comradeship of my companions of the road," Pons wrote.

"He tried all the options to try and, you know, get the Mototri out of there," Tony says. "But he had to leave all spare parts. He had to leave the trike."

Pons and Foucauld eventually made it back home, riding with a caravan of camels part of the way.

When Pons’ account was printed in a French magazine two months later — in late August 1907 — Prince Scipione Borghese had already arrived in Paris, three weeks ahead of the second-place finisher. Nobody ever went back for Auguste Pons and Oscar Foucauld.

"But it’s already old history. We cheer those who finish the race," Pons wrote. "And I have already been forgotten."

'Making It A Happy Ending'

On day three of the 2019 rally, Anton Gonnissen had made it further than Pons ever had, but he was still in Mongolia, and he had yet to face his biggest challenge.

"Let's skip ahead to day seven," I say. "What happened with your axle then?"

"We drove into the campsite," Anton says. "And I saw people looking at my wheels."

Anton already knew something was going on with his wheels. He’d been staring at them all day. But, just as he and Herman pulled into the campsite, the axle broke completely. The only thing holding the trike together was the pipe that had been inserted into the axle on day two.

"Again, for the second time, I was sure, nearly sure, that the rally was finished," Anton says. "So I was a bit heartbroken for 10 minutes."

The repair took four or five hours, but eventually a Mongolian welder was able to use a rusted piece of scrap metal to fortify the axle.

"At that moment, I sort of realized that probably we were going to make it," Anton says.

I don’t want to say that the rest of the journey was easy. In fact, it was miserable. By the end, Anton Gonnissen could no longer feel two fingers on each hand — they had gone numb from the vibrations coming up the handlebars. But he and Herman passed through Mongolia, then Russia, Kazakhstan, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Poland and into Germany.

"Once in Germany, you know you're there. Actually, you know you're there. Nothing is gonna go wrong there," Anton says. "And even if it does, you can fix it."

"So take me to the end of the rally. How did it feel to actually legitimately finish this thing that Pons had started?"I ask.

"That's a good question," Anton says. "It didn't — I didn't [feel] anything. So when I arrived in Paris, I thought that the world would be too small, and that explosions would happen in my head, and that I would dance on this amazing, beautiful square. I didn't. I was just extremely happy that it stopped. That it was done. It only came to me a week or so after. Slowly, in bits and pieces.

"I really think — it sounds silly — but, 1907, five teams set out to do something incredible. Four of them arrive. One gets stuck in the Gobi Desert, goes back home. Nobody talks about him anymore. He gets forgotten. Finished. I pick it up 112 years later. I think that the gold medal is his. Or at least his and mine. So what I will do, I'll go back to Paris and put the medal on his grave, making it a happy ending."

Actor Benjamin Bailleux read the words of August Pons. Arlo-Moore Bloom helped produce this story.

This segment aired on December 14, 2019.