Advertisement

For 70 Years, Allied Navies Fought Over This Old Photo Of Esther Williams

Like every good romantic comedy, this story begins with a classic Hollywood “meet cute.”

Edward Bell was producing promotional events for the 1984 Olympics.

One day he got a call from McDonald’s wondering if he could find a celebrity from the sport of swimming.

"I said, 'Well. There's Buster Crabbe,' " Edward says.

Buster Crabbe was an actor who won gold in the freestyle at the 1932 Olympics. But Buster Crabbe didn’t work out.

"And they said, 'Do you know anybody else?' " Edward says. "And I said, 'Well, yeah. Esther Williams.' And they said, 'Fine, can you get her?' And I said, 'Oh, yeah, sure.' "

Edward didn’t actually know Esther Williams. But he did own a telephone.

"So I picked up the telephone, and I called her. And I told her what we needed," Edward says. "She said, 'Would you like to meet for lunch?' Of course I'd like to meet for lunch. Esther Williams, I saw her movies at Radio City Music Hall when I was a kid."

Edward arranged to meet Esther at a restaurant in LA.

"She was late. She was an hour late. And when I saw her walk in, I stood up and knocked the whole table over. Everything. The wine, the glass and everything. She thought that was very funny," Edward says.

Edward says he doesn't remember much about the rest of the lunch.

"I think I was so taken by the fact that — I loved movie stars, I knew a lot of them. But it was — she was extraordinary. She was so charming and bright that I just, I was so taken with her," Edward says.

Advertisement

McDonald’s ended up going in another direction, but Edward helped Esther get a different job at those Olympic Games.

"NBC was looking for commentators, because it was [the] first Olympics they had synchronized swimming," Edward says. "And Esther was referred to as 'the mother of synchronized swimming.' "

Esther Williams had almost gone to the Olympics herself. In 1939, she was the reigning American 100-meter freestyle champion.

"But, in 1940, the Olympics were canceled because of the war. So, as Esther said, 'As compensation, I became a movie star.' "

Esther's first movie was 'Andy Hardy's Double Life' with Mickey Rooney. "She gave Mickey Rooney an underwater kiss," Edward says.

Esther Williams starred in a new kind of movie – called "aqua musicals." They were huge MGM productions that spotlighted Esther’s grace and power as a swimmer.

"And I think, instinctively, women felt empowered by her. She was athletic, strong and powerful. I was very proud of her. She had this strength about her. This strength about her as a woman," Bell says.

Maybe you’ve already figured this out, but Edward and Esther fell in love.

"I was her fourth husband," Bell says. "She was my third wife. And we lasted for 30 years. We had a wonderful, wonderful relationship."

The Prize, The Face And The Voice

Esther Williams died in 2013. And I didn’t call Edward Bell to talk about her career. I called him because I recently learned that this swimmer-turned-movie star was the prize, the face and the voice of an international military competition that spanned seven decades.

"Aren't soldiers silly?" Bell says. "They're goofy."

"We've got lots of ways of being stupid in the armed forces," says military historian Dr. Tom Lewis.

Tom served in the Australian Navy for 20 years. And it wasn’t long after he joined in 1983 that he first heard about the Esther Williams Trophy.

"I think I remember thinking that it was just one of those trophies that ships compete for," Tom says. "So you do have competitions in sport, you have competitions for best gunnery ship and things like that. So I would have thought it was just one of those type trophies."

But it wasn’t, as Tom learned on a visit to a place called Spectacle Island.

"Spectacle Island is so called, because it was two islands joined by a little strip of land," Tom says. "They have these huge warehouses. They're incredible. They're a couple of hundred meters long — each of them — and air conditioned."

Spectacle Island is where the Australian Navy keeps its most prized artifacts. And it was there that Tom first saw the framed photo that the Australian Navy — and, later, the British, American and Canadian Navies — fought over from 1943 until Esther’s death in 2013.

"It's a rather odd looking thing and a rather odd concept of a trophy," Tom says.

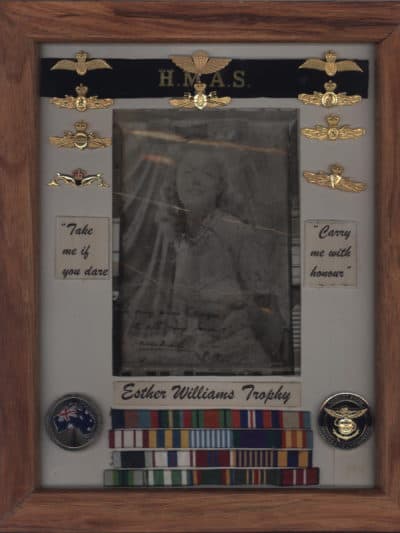

Over the years, a few copies of the Esther Williams Trophy have been made. The one Tom saw is called the "fighting copy." It’s a signed photo of a smiling Esther in a wooden frame inscribed with "Take me if you dare" and "Carry me with honor."

You’re probably picturing a photo of Esther Williams in a swimsuit with legs for days. But Edward Bell wants you to know this wasn’t that.

"It's not like Rita Hayworth or Betty Grable, where you were showing legs and bodies. This was a pretty picture," Edward says. "Looks like a star."

"She was the prettiest thing in the Pacific at that time. You know, it was wartime at the time, 1943," says William Fury, U.S. Navy, retired.

He first saw the Esther Williams Trophy in 1956 while serving aboard the aircraft carrier USS Boxer.

"She was the only picture that was on any of those ships, okay? We had a pin-ups, but they had to be in your locker," Fury says.

The Rules Of Engagement

But the Esther Williams Trophy could be displayed, right out in the open. In fact, that was one of the rules. If you "liberated" the trophy from another ship, you had to display it in your wardroom — the officer’s mess.

There were other rules, too.

- The trophy is to remain unsecured and in full view.

- The trophy may only be removed by force (preferably of the brute variety) or by exceedingly low cunning and vile stealth.

- Use of enlisted personnel in any fashion is prohibited.

- The only other restriction is against firearms and clubs.

- Unsuccessful suitors are to be given haircuts and lodging.

" 'Haircuts and lodging' would mean you probably have half your hair shaved off, and you'll be locked inside a bathroom for a couple of hours, or something like that," historian Tom Lewis says.

And did you catch that bit that prohibited the use of enlisted personnel? This was a game for officers. And William Fury was enlisted. Which meant, instead of khakis, he wore dungarees — we’d call them jeans today.

He continues his story...

"One of the officers come up to me, and he says, 'Hey, you're my size. Can I borrow your clothes?' I say, 'What are you gonna do, rob a bank, or what?' You know? So, "No, no, no, no, no, no." He says, 'You'll see.' So, anyway, I gave him my dungarees. And he went over to the USS Salem, and they went aboard and stole the picture of Esther Williams. And they brought it back and put it aboard our ship. And then the rest of the ships were all trying to steal it off us. It was a game."

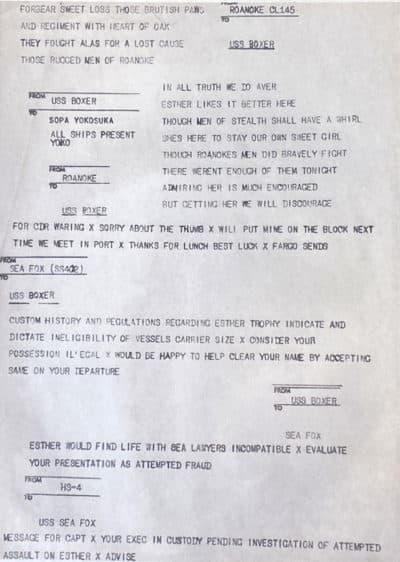

Once a ship captured Esther, they had to do two things. They’d fly a pennant — a special flag that let the rest of the fleet know that Esther was aboard.

And they’d send out a message, often written as if Esther herself was sending it, letting the fleet know that she’d been rescued.

THE IDEA OF FACING ANOTHER WINTER BOUNCING ALL OVER THE WEST AUSTRALIAN EXERCISE AREA MAKES ME A LITTLE CHUKY. I AM SICK OF FEELING GREEN AND VERY KEEN TO FEEL BLUE.

Those messages would end with...

ESTHER WILLIAMS SENDS

While in port, the Boxer was connected — via long ropes — to two submarines.

"Conventionals," William says. "They weren't nukes at that time."

And, once the submarine officers learned that Esther was aboard the Boxer, they attacked.

"Submarine officers [came] aboard our ship and threw a smoke bomb in the hangar deck," William says. "And we went to fire quarters. Everybody runs to their battle stations or fire quarters. Okay. Everybody's got a place to be."

And if you think sending sailors to battle stations over a photo of a swimmer-turned-movie star sounds dangerous, you’d be right. Many a raid for the Esther Williams Trophy ended with injuries and water rescues.

The attackers took Esther and sped back to their submarine. The Boxer’s officers pursued them, but when they climbed aboard the sub and started to try to open the hatches, the sub suddenly submerged.

"The submarine is submerging right there, and they're all floating on top of it. So that was the end of that. They lost the battle," William says with a chuckle.

Canada Joins The Fun

Les Wood served in the Canadian Navy for 28 years. He crossed paths with the Esther William trophy sometime during the Korean War. He doesn’t remember the exact year.

So, sometime during the Korean War, Les and his fellow officers of the HMCS Haida were invited over to another Canadian ship to see the trophy.

"And Canadian ships, of course, they have liquor," Les says. "So we went in and had a few drinks. And they brought out the Esther Williams trophy, showed it to everybody. And everybody was passing it around.

"And we had heard about the trophy as being things that the ships were having fun trying to steal from each other. So I was talking to one of my friends, and I said, 'You know, just for fun, we should steal it.' And he says, 'Good idea.' "

"I was talking to one of my friends, and I said, 'You know, just for fun, we should steal it.' And he says, 'Good idea.' "

Les Wood

Les and his friend had noticed that the ship’s gangway went right past one of the wardroom windows, or portholes. And it was open.

"And he went outside and down the ladder right past the porthole," Les says. "The rest of us passed it around until we got to the window or the porthole. And I passed it out to him. He took it, and took off to our ship. Took the trophy and hid it there."

And here’s where we get to the final rule of the Esther Williams trophy — it had to stay in the Pacific. And Les Wood and the Haida were about to head back home.

"There were three American ships there, too. And we passed the trophy to them," Les says. "And, of course, every other ship in the fleet now was after these three ships. So, when we sailed out the harbor that day, it was like a war going on, with fire hoses and everything else. And I don't know who ever got it in the end, but that's the last I saw of it."

An Unsucessful Retirement

The Esther Williams Trophy was retired in 1957. And that should have been the end of the story.

But Mick De Jong came across the Esther Williams trophy much later, in the 2000’s. He’s not in the Navy, but he spends months at a time cruising around in his sailboat. When he first saw the trophy, he was sailing the Wessel Islands in a very remote part of Australia’s Northern Territory.

"And, honestly, you just don't see a boat up there at all," Mick says. "And, in the bay just north of us, I saw a small patrol boat come in and anchor. It was a good five miles away."

Mick’s partner, Sheryl, has a brother in the Navy. And so they looked at each other and thought, 'Wouldn’t it be amazing if Sheryl’s brother was on that ship?'

Mick radioed the ship and, believe it or not, Sheryl’s brother was there. Mick and Sheryl were invited aboard.

"And, at the end of that tour, we were in the wardroom — the officer's mess. And on the wall was a picture of Esther Williams," Mick says. "The XO was showing us around — the second in charge of the ship — and I asked him, 'What's this all about?' And he said, 'Oh, that's a great story.' "

Turns out that back in 1997, 40 years after the trophy had been retired, it was being housed on Spectacle Island. You remember Spectacle Island — that place with the Navy’s most precious artifacts?

The officers of the HMAS Brisbane were there on a visit.

"Being shown through by the curator of the museum," Mick says. "And the museum curator was sort of saying, 'Back when men was real men, this was the Esther Williams trophy. And we used to fight for this.' And this is all speculation, of course."

Mick has no idea what was really said. But, whatever it was, the officers of the Brisbane took the curator’s words as a challenge.

"At the end of the tour, they said, 'We'd like to invite you back to the HMAS Brisbane,' " Mick says, continuing the story. "So, the next day, the curator of the museum comes to the HMAS Brisbane, they show him through. And at the end they said, 'We've got a presentation to make for you.' And they hand him over the stolen item."

After a 40 year hiatus, the Esther Williams trophy was back in service.

Over the years, some of the sailors wrote to Esther Williams — the real one, back in Hollywood — and they’d tell her of her trophy’s grand adventures in the Pacific. Esther would sometimes write back. Edward Bell says she was honored and a bit amazed by all the fuss.

"She had a good feeling about the trophy," Edward says, "that she was part of this."

Finding Lindsay Brand

And there’s one more story about the Esther Williams trophy I want to tell.

See, for many years, nobody was really sure how this whole thing got started. There were rumors. One popular tale suggested that a young officer named Georgie had told his mates that Esther Williams was his fiancée— and they stole the photo to teach him a lesson.

When Mick De Jong got back home from that sailing trip in the early 2000s, he decided to try to find the original owner of the photo. Mick’s only lead was the sailor’s name: Leslie Brand.

"We've got literally thousands of L. Brands in every state," Mick says. "So I thought, 'I'm never, ever gonna find this fella.' So I had picked one phone number out of all these phone numbers. And I thought, 'Ahh, I’ll just give it a go.' So I rang, and I got an answering machine saying, "Hello. You've got Lindsay and Betty Brand. Please leave a message after the beep.' I couldn't believe my luck."

Mick left a message, but he didn't heard back. A few days later, he called again.

"And I got hold of Betty," Mick says, "and she goes, 'Who are you? What do you want?' And I said, 'Look, I'm just, you know, doing some research on the Esther Williams trophy.' 'How do you know about the Esther Williams Trophy? That's just a story he tells the kids.' "

By this time, the Esther Williams trophy had changed hands more than 200 times and been held by ships from four different Navies. And Lindsay, Betty, and the kids — who were now in their sixties — had no idea.

"Betty said, 'Oh, he's gonna want to talk to you.' And I told Lindsey the full story," Mick says. "And he goes, 'I think I'm going to need a stiff drink.' "

And that’s when Mick De Jong was finally able to answer the biggest question of them all: How did a swimmer-turned movie star become the prize, the face and the voice of an international military competition that spanned seven decades?

The Origins Of The Trophy

It started with Lindsay Brand and Captain David Stevenson. They were in Durban, South Africa.

"They were both frequenting the Stardust nightclub and both trying to, you know, pick up a certain young lady," Mick says.

Just to be perfectly clear, this ‘certain young lady’ was not named Esther Williams.

Lindsay Brand tells the story in his unpublished memoir, "A Fortunate War."

"David Stevenson, pleased with himself for having beaten me for the honor of squiring a certain young lady, presented me with a framed photo of a luscious and eminently kissable Esther Williams," Lindsay wrote.

The captain signed the photo, “To my own Georgie, with all my love and a passionate kiss.”

"Why did he sign it as 'Georgie'?," Mick asks. "Well, as they were passing each other— any officer was passing each other on the ship. You would call him 'Georgie, and he would call you 'Charlie.' Or you'd call him 'Charlie,' 'G’day, Georgie.' "

This was during the war, remember? Officers were targets.

"That was going to be the end of the story," Lindsay said in an interview for a documentary. "I had this lovely picture of Esther. But then someone came along out of the blue, went into my cabin and took it away."

That wouldn’t do. So, Lindsay got some help and stole his photo back.

"No bloodshed. No blows. No nothing. Just – we took it," Lindsay said.

And that’s really all there was to that.

A few years after Mick found Lindsay Brand, the Australian Navy arranged a ceremony to re-unite the sailor with his picture of Esther Williams — if only temporarily.

And then, in 2010, Lindsay Brand died.

"I found Lindsay only a few years before he passed away," Mick says, "So I got to tell him all those years later that something that he and Captain Stevenson started was such a great morale booster for all the allied Navies. And it just went on for so many years. What a great tradition."

When Esther Williams died in 2013, the Australian Navy officially retired her trophy ... again. They sent out one more ship-to-ship communication:

I WAS THE MERMAID OF THE AUSTRALIAN NAVY

THE DESIRE OF ALL WHO GO TO SEA

WHOSE PRAISE I LOUDLY CHANT

THROUGH THE WATER I DID GLIDE

MY FACE CHARMED ALL ALONGSIDE

AND I TRAVELLED ACROSS MANY CHARTS

BUT NOW THE SUN HAS CEASED TO SHINE

YOUR ATTENTIONS I MUST NOW DECLINE

AND SEEK THE SECLUSION THE HERITAGE CENTER GRANTS

FOR THE FINAL TIME

ESTHER WILLIAMS SENDS

This time, instead of keeping Esther in one of those warehouses at Spectacle Island, every known copy of the trophy is on display in the Royal Australian Navy Heritage Centre in Sydney — open to the public, but locked away under glass.

Presumably to prevent further theft.

This segment aired on February 8, 2020.