Advertisement

Lessons From A 2013 Tunisian Soccer Match And A Phone App

As sports leagues return to play in empty stadiums, some broadcasters have been experimenting with adding fake crowd noise to make those stadiums sound less empty. But that experiment hasn't always been well-received.

"Throughout [the] recent history of sports, people have really turned their nose at the idea of pumping in crowd noise to stadiums," says the Wall Street Journal’s Andrew Beaton. "You know, it was almost seen as a form of odd cheating."

The problem, Andrew says, is authenticity. Fake crowd noise — no matter how well it’s done — just feels fake.

But in March of 2013, a Tunisian soccer team called Club Sportif de Hammam-Lif positioned 40 speakers around their home stadium and invited their fans to cheer on the team for real ... sort of.

"Long before we were thinking about the Bundesliga or the Premier League or baseball playing in empty stadiums, they had come up with a kind of work around to let fans make their voices heard in real time," says the Wall Street Journal's Joshua Robinson.

KG: OK. So in a lot of ways, this story starts with the Arab Spring. Can you just give us a quick reminder of where and how the Arab Spring began?

AB: Well, the Arab Spring — one of the interesting things is while, globally, we paid attention to it in countries such as Egypt and others much more, Tunisia was actually, in a lot of ways, the launching off point for what became a really phenomenally important movement.

JR: The effect of the Spring lasted for years. They banned all large gatherings. And so you couldn't have sports games, which had been tens of thousands of people, because the fear was that any time people were allowed to gather in those kinds of numbers, there might be another riot. It might turn political, and they wouldn't be able to contain it.

KG: So we're in March of 2013. That's two years after the start of the Arab Spring. Fans are still at home and a soccer club called Hammam Lif is facing relegation. Can you describe this team for me?

AB: You know, it's a team that, even in Tunisia, there are bigger clubs. There are clubs that have had more success. This wasn't exactly a powerhouse, but this soccer club is a point of pride in a soccer obsessed nation. And this is a city that clearly loved its soccer team but also had no way to actually go and show their support for them when they were on the brink.

KG: And that's where an advertising and marketing agency called Memac Ogilvy enters the picture. Josh, who are they and what had they been working on?

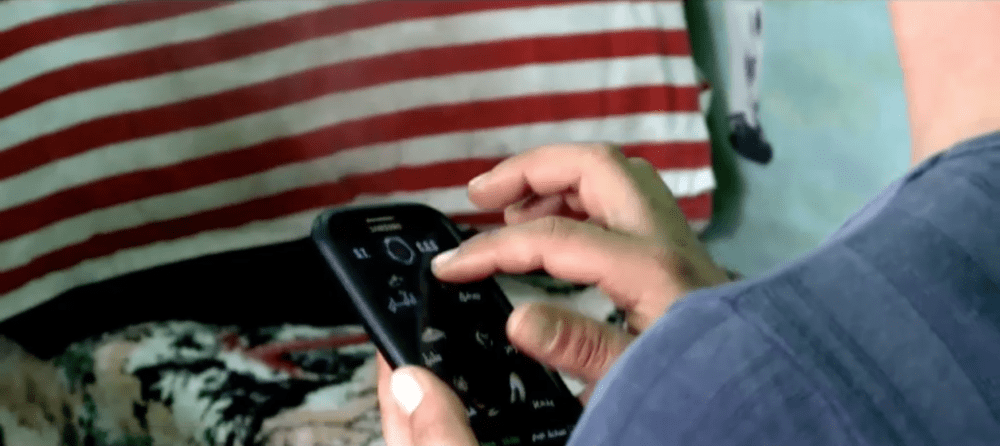

JR: So they're a major international ad firm. And they had been toying with an app that would allow fans to somehow participate in the atmosphere. The atmosphere, as we've all found out recently, is pretty weird in an empty stadium when you can hear the players and the coaches, and there's nothing else going on. There's no soundtrack. What the app did was allow them to broadcast a number of cheers or noises via a speaker system in the stadium just by tapping their phone screens.

KG: So what did it actually look like? Like, if I had it on my phone. What could I do with it?

JR: You open up the app, you get this home screen. You can either clap or make a horn noise or make a drum sound.

AB: If you're watching it on television, then you could hear the result of your tapping. And I think one of the things that's really fascinating about the idea is that there's two elements to when fans are in the stadium cheering; first of all, when something exciting happens, there's this roar in the crowd. Or, if there's something terrible happen[ing], there are these groans.

But there's this other element of, you know, when you're at the game and it's a way to feel as if you are contributing, if you are helping cheer your team on. And so one of the things that fascinated us about this idea is that, in an odd way, it solves both of those. Because it both accounts for creating this noise. But also it's not just playing a soundtrack of fans cheering and playing the drums, or sounding horns. It actually requires people to actively be engaging in creating this noise inside the stadium.

Advertisement

KG: OK, so take me to the day of the game where this was first used.

JR: Hammam-Lif needed a win. It was late in the season, and they would have been relegated or very close to it if they hadn't won. Once the game starts, and once the app is engaged, you would have heard 90,000 fans channeled through this app tapping their phones while this game goes on. And it's it's tense for a long time. And, ultimately, it was a Hammam-Lif one nil victory that we suspect had something to do with the noise. But it's impossible for us to prove.

KG: Well that was gonna be my next question. I mean, it was clearly the fan support that made them win, right?

JR: Well, they were not an amazing team so you have to believe it had some effect.

KG: It sounds like a lot of time and money was put into creating this technology. Why was it never used again?

AB: So they have this great idea, this roaring success. I don't think anybody imagined that this many people would use it. And the next year, the state of the country had calmed to the point where they felt comfortable allowing mass gatherings. People could go and attend matches. But the funny thing is we're looking at the world now, and it's oddly relevant.

KG: So let's bring this story to today. As sports events begin to resume, fans are being told to stay at home not because of political unrest, though there is plenty of that, but because of a pandemic. What have athletes been saying about what it's like to compete in these empty venues?

JR: It's taken a lot of getting used to for everyone who's had to do it. They're all discovering, maybe for the first time in their careers, what it's like to walk out of the tunnel and see no one in the stands — hear nothing — except themselves and their own thoughts, sometimes. We're seeing a lot of experimentation right now with how to create a soundtrack for stadiums. In the German Bundesliga, for instance, they're giving broadcasters the option to play recordings of fans so that it doesn't feel quite as jarring on television.

"The phenomenal thing is this Tunisian soccer team is a model for them."

Andrew Beaton

JR: In Denmark, we're seeing some experimentation where the one club is trying a drive-in kind of setup, where 2,000 fans can just drive up and watch the game from just outside the stadium. And another club, Aarhus, has tried putting three giant screens, where fans can use Zoom to actually project themselves into the stadium. But, while these are maybe a little more high tech or a little more modern twists on the Hammam-Lif experiment, everyone who's trying something now, whether they know it or not, owes a debt of gratitude to Hammam-Lif in 2013.

KG: So do you think we're going to see some version of this app in the next few months?

AB: I think the question isn't necessarily whether or not we see this exact app. But I think there's almost no doubt that we are going to see teams across the world doing these exact same things. American sports fans, they're used to feeling an excitement when you turn on a game and you know what you're watching is exciting and important, because you see 90,000 people screaming their heads off inside the stadium. They have packed themselves in like sardines for that right to spill beer on each other and cheer.

We don't know exactly what the fan situations might look like when an NFL game kicks off in September. But we do know that they need to find a way to make the experiences exciting. And you know that these sports leagues worth billions upon billions of dollars are right now — while they're trying to return — turning over every stone trying to figure it out.

And the phenomenal thing is this Tunisian soccer team is a model for them.

Check out Andrew Beaton and Joshua Robinson's piece “The 90,000 Fans Who Screamed in an Empty Stadium.”

This segment aired on June 20, 2020.