Advertisement

How Cherelle George Found A Home With The Harlem Globetrotters

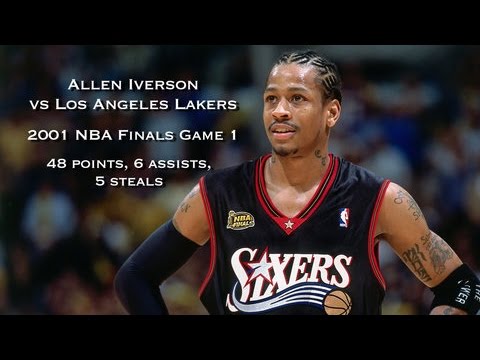

Basketball fans call it one of the greatest moments in NBA history.

It all went down during Game 1 of the 2001 Finals: The Los Angeles Lakers vs. the Philadelphia 76ers.

Most people had placed their bets on the Lakers sweeping the series.

But among those who were rooting for the underdog was one girl who never, ever, ever missed a Sixers game — at least, not after she first saw Allen Iverson suit up for Philly.

"Honestly, Allen Iverson was the one player that I felt like changed my life," Cherelle George says. "He was, like, my hero."

'I Want To Do That'

Cherelle was a 16-year-old, 5-foot-3 aspiring point guard, who often joked that she had to throw the ball up rather high to make a layup. By high school, she realized that she wasn’t going to get much taller. But Iverson, standing at 6 feet even, gave Cherelle hope. He was proof that short people could ball. And, if she had any remaining doubts, his performance in Game 1 snuffed them out.

Cherelle sat at home, eyes glued to the TV as she watched him sink basket after basket — just tearing the Lakers apart. By the time the final whistle blew at the end of overtime, he’d have a whopping 48 points and a win. But, right before that, he pulled a move that would become a viral internet meme in years to come. Cherelle could never forget it:

"He jab steps, takes a dribble, crossover, shoots it like a fadeaway," Cherelle remembers. "Tyronn Lue contests the shot. Allen Iverson still makes the shot."

Tyronn Lue tripped and fell to the ground.

"And then Allen Iverson steps over Tyronn Lue and kinda, like, gives him a look," Cherelle continues. "And I was like, 'Oh, my God. This is awesome.' Like, I want to do that.' "

As soon as she got the chance, Cherelle went outside and practiced that crossover fadeaway shot over and over again. But Cherelle didn’t want to be Iverson’s carbon copy. Every time she hit the court, she was feeling out her style, figuring out how to make it to the top in her own way.

An Obsession With Basketball

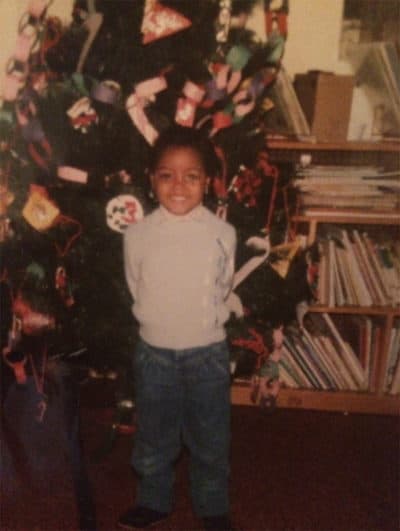

Cherelle hails from the projects of Reading, Pennsylvania, where kids in the neighborhood played streetball nearly every day. When she was 4, her mother noticed that her daughter loved trying to play with the neighbors, despite her tiny hands. So on Christmas Eve, Santa dropped off the perfect present.

Advertisement

"I woke up the next morning to a Fisher Price hoop and a basketball. And I just remember bouncing it all day, like, being so excited," Cherelle recalls. "I played every day after that. And as I got taller — which, I mean not much taller — I would raise it up, and I would dunk on it."

Dunking was fun and all, but Cherelle found that dribbling was her real bread and butter. You could often find her watching the men at the local court, or in front of the TV, rewinding and rewatching And1 mixtapes.

"I was that kid who would go in my room in the dark and would just dribble in the dark," Cherelle says. "Just dribble, no lights. Just in the dark, in my room, sometimes eyes closed. And it would drive my mom crazy."

Poor Ms. Holly George didn’t get much sleep with Cherelle around.

"On the weekends, we would get up — I would get up super early. Like, if I knew we had a game at 10 a.m., I’m up at 5 o'clock in the morning," Cherelle says. "Just tugging [at] my mom, like, 'Get up, Mom!'

"She'd be like, 'Girl, your game ain't 'till 10. We have time.' But I would just like, 'Don't forget. Set your alarm. Don’t forget.' My mother didn’t always have a car, so we would walk hours to my games. And I know my mom would be tired, but I knew she knew that it would pay off."

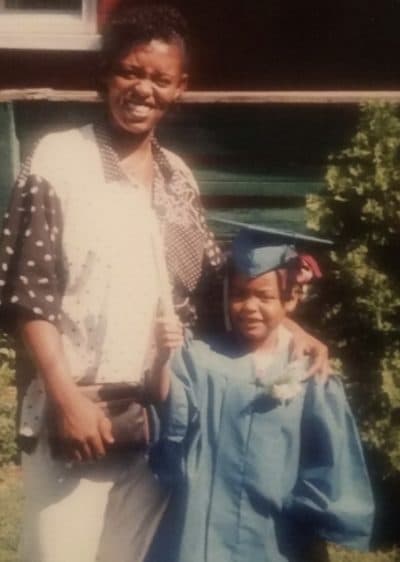

During the summer blacktop league, Cherelle was playing on boys' teams and dominating — wowing everyone with her skills. And, when her family moved to Georgia, she became a star on her middle school team. It was clear to her mom that basketball could be Cherelle’s ticket out of the projects. It could give her access to a free college education, and who knew — maybe an opportunity to travel the world.

But there was one aspect of Cherelle’s game that coaches — and even her mom sometimes — thought could get in the way.

"I was in the seventh grade, and we were in a championship game," Cherrell recalls. "And it was 20 seconds left, and we were up by two. So the coach is telling me, 'Cherelle, pass the ball around, move the ball, we got 20 seconds!' And I literally dribbled out the ball for 20 seconds. I put on, like, a dribbling show for 20 seconds, just going between my legs. Just razzle-dazzle. And everybody was just going crazy. So anytime I got that spotlight to display what I had been working on in my room and the courts, I took advantage of it.

"Coaches would call me 'showboat,' but I was the hardest worker on the court. Like, offense, defense. I wanted to guard the best player. It was just a part of my game. This is who I am."

A Dream Come True ... And A Setback

During her junior and senior years at Newnan High School, Cherelle scored over 1,000 points and became a McDonald’s All-American nominee. That’s one of the highest honors you can earn as a high school basketball player. Soon, college recruitment letters were piling into her mailbox.

The thing was, Cherelle’s ACT scores weren’t good enough. So she opted to play at Iowa Western, a two-year junior college, where she planned on improving her academics so she could eventually play at a top Division I school. But there, her playing style wasn’t quite cutting it.

"My head coach was old school — very fundamentally sound," Cherelle says. "So me and him clashed my freshman year. I remember thinking, like, for the first time, 'Man, maybe I can’t be who I am. Maybe I do have to change my game for the team.' There were a couple games where, you know, I’ll make a flashy layup. Or I’ll do an extra between the leg or a razzle-dazzle move. And he’ll just like, 'You’re out. Come and get her out.' Even if I made the basket.

"My mother was — oh my God — telling everybody. You know, I remember her saying, 'We made it.' "

Cherelle George

"And I remember being super frustrated and crying a lot and not being happy — even wanted to transfer from Iowa Western, because I felt like, you know, I just couldn't be myself.

"He ... constantly instilled in me like, 'Cherelle, I'm telling you: You want to play big-time Division I basketball? Less flash, and just keep it basic and fundamental.' "

Cherelle then began to tone it down — buy into her coach’s program — and in many ways, it paid off. Her sophomore year, she became captain and dropped 25 points a game. She was breaking records, earning accolades and getting even more attention from college scouts.

Then the day she and her mom dreamed of finally came. In 2005, she signed with Purdue University, one of the top women’s basketball programs in the country.

"I became a Boilermaker. Yes. I was excited," Cherelle says. "My mother was — oh, my God — telling everybody. You know, I remember her saying, 'We made it,' You know. 'We made it.' "

Unfortunately, the basketball powerhouse didn’t ever become a real home for Cherelle.

In 2006, the school self-reported six NCAA violations involving the coaching staff, one of which involved Cherelle, who had asked one of the assistants to help her edit a paper.

Purdue suspended the coach and Cherelle indefinitely for "academic misconduct," an accusation that Cherelle calls an unfortunate mix-up.

"I remember calling my mother and being, like, 'Man, I don’t even know how to explain this to you,' " Cherelle says. "Because I knew she would be so hurt and disappointed. Especially knowing that I’m not the type of player that’s ever been in trouble at any university, not in high school, for anything."

What made it worse? Her suspension prevented her from transferring to another team. So Cherelle had to train on her own to make it to the pros. Two years later, she and her sister made a 10 hour road trip down to Texas for a WNBA combine. Scouts from the Indiana Fever liked what they saw and called her into training camp to see if she could make the final cut. She didn’t.

"They said, 'You didn't make the final cut. But don't give up.' Like, 'You did great.' You know what I mean? 'You definitely deserve to be in this league.' And I felt like the coach meant it," Cherelle says.

Cherelle returned to Georgia and kept on training for that next opportunity. She got a job at a recreation center and looked for chances to play professionally overseas.

Then, on Aug. 21, 2010, she got a call.

"It was midnight," Cherelle recalls. "And I was in my apartment in Carrollton. And my sister was living with me at the time. She was downstairs, and I heard her scream. And I was like, 'Rami, are you OK?'

"And she just gave me the phone. And I hear this gentleman’s voice. He said, 'I’m from the coroner’s office. I have your mother’s body. Holly George.' "

Losing Her Hero And Best Friend

Their mother had a heart attack while driving on the freeway. Officials found her dead at the wheel. Cherelle had lost her hero and best friend. It was all too much for her to bear.

The stress of it manifested physically. Cherelle's heart was constantly beating rapidly, but she thought it was just adrenaline. She lost her appetite and was losing weight fast, but she thought it was just grief.

Then, before the funeral, her aunt noticed that Cherelle’s eyes were bulging out of their sockets, and there was swelling around her neck. Her aunt told her to see a doctor as soon as possible. Blood tests confirmed that Cherelle had Graves’ disease, an incurable thyroid disorder that can cause hair loss, bone damage, stroke and heart failure.

Without the proper medication to manage it, Cherelle’s life was in danger. And her basketball career? Forget it. It was too risky.

For most people with Graves' disease, finding the right medicine can be incredibly tricky. Cherelle’s case wasn’t any different. Her doctors put her on a drug called Propranolol, and while Cherelle’s heart rate improved, her hair kept falling out, she felt tired all the time and she was gaining weight like crazy.

"I was at 180 [pounds]. Imagine that," Cherelle says. "I have a picture of myself, which I don’t share with anybody. You can’t even see my eyes. That’s how big my face is."

After two months of frequent appointments — after having lost her mom and the game that gave her life — Cherelle walked into her doctor’s office frustrated and fed up.

"And I said, 'I'm done,' " she recalls. " 'I'm not taking this anymore.' He said, 'You can't go cold turkey off the Propranolol. You'll be dead in six months.' I remember just looking him in his eyes and saying, 'I'm already dead.'

"I wanted to get rid of this disease, I wanted my body to stop attacking itself. I wanted to feel like me again. I wanted to live.

"I remember leaving his office and getting in my car thinking like, 'You’re not gonna come in this office any more. It’s up to you now.' "

"I wanted to get rid of this disease. I wanted my body to stop attacking itself. I wanted to feel like me again. I wanted to live."

Cherelle George

Cherelle then began a long journey of trial and error, trying to figure out what her body needed. She was taking a risk by ignoring her doctor’s advice but, over time, her health started to improve. She was doing everything: cutting out processed foods, eating raw, taking this herb and that vitamin; she did acupuncture and cupping; saw a naturopathic doctor. Cherelle also moved to Florida hoping that a new environment would help in her healing.

"I had been in Florida for six months, and [the doctor] gave me a call and she's like, 'You know what? I think it's bloodwork time. Let's take your bloodwork. Last time it was amazing. Let’s see where it's at now,' " Cherelle says. "And so I remember walking in and getting my bloodwork done to check my thyroid levels, and they were normal. She was like, 'You can get back to playing basketball. You’re good. There's nothing.' And I remember just bawling my eyes out."

An Unexpected Offer

"After three years of just ... fighting for my life, fighting for my body back, fighting for me — I just remember feeling overjoyed and just like, 'I gotta find a team to play for,' " Cherelle says.

Cherelle found a semi pro team called the Miami Lady Bulls, and she even started a successful youth basketball program. Her life was coming back together better than ever before, and she had everything she needed: basketball and her health. The fundamentals.

One day, she was at a tournament coaching one of her travel teams, when she had an itch to train. In between games, she grabbed a ball and found an open court to practice her drills. Little did she know: Somebody was watching. It was one of the refs.

"He comes up to me, and he’s like ... 'I think you could play for the Globetrotters.' "

Cherelle George

"He comes up to me, and he’s like, 'Hey, my name is Keith Arnett, and I've been watching you on the side do your thing," Cherelle recalls. "You can really handle the ball, like, you can play. I'm a former Harlem Globetrotter referee, and I think you could play for the Globetrotters."

That’s right, the Harlem Globetrotters. You know, that basketball troupe of entertainers famous for their jaw-dropping trick shots, fancy handles, and sideline pranks?

"I'm like, 'Eh, man, quit playing with me,' " Cherelle says. "Like, 'OK. Whatever.' He’s like, 'Well, I got the contact of the scout.' "

Keith wanted Cherelle to send videos to the scout right away. But Cherelle had just settled into her new life. She didn’t want to risk losing everything again for a shot at something that might not work out. But Keith was so persistent that she finally gave in and sent her videos.

"And about 10 minutes later, I get a call. Not kidding you," she says. "And it's the Harlem Globetrotters' scout. 'I'm wanting to fly you out to Atlanta to audition.' And I'm like, 'No way. Like, this is really happening. He wasn’t lying.' "

Now, at the tryout, Cherelle would tell you that she didn’t have any tricks. If the coaches asked her to spin the ball on her finger or roll the ball off her chest, she’d be in trouble. But, while she didn’t have those special maneuvers up her sleeve, she had her inner child in her back pocket.

That young woman who had some Iverson swag in her step. The little girl who studied And1 moves like it was her job. And for the first time in a while, she didn’t have to hold back. She pulled out her secret weapon: the between-the-leg-tumble dribble — a move that looks as difficult as it sounds.

The coaches were sold. They loved her energy, loved the way she just lit up the court.

In 2017, Cherelle signed for her first tour in Kentucky. And, as the crowd cheered to welcome her to the court, she was reintroduced to the world by her new name: Torch.

Living The Dream

Today, Torch is a professional showboat with no one to tell her to "tone it down," to do things their way, or "stick to the basics."

In 2018, she completed a record-breaking 32 between-the-leg-tumble dribbles in a minute. That feat cemented her as the first female Globetrotter to make the Guiness Book of World Records.

"To think I was doing that as a child, just doing it, and now that move that I did in the 'hood, it’s got me in the history books," Cherelle says. "So many little girls reached out to me via social media and sent me messages like, 'Man, you inspired me, and I want my own Guinness World Record now.' Even boys, like, ‘I don't know how you did that move.' Like, 'I've been practicing it since I've seen you do it. I can't do it. I don't know how you did it. Is that real?’ I'm like, 'Yeah it's real.'

"I'm just living to inspire these young kids, now. These young boys and girls who have dreams just like me — who come from the inner city, just like me. Every single day, I put on that jersey, and every city we go to, every game, I feel like, 'Man, I've made it.'

"I'm living the life that me and my mother always used to speak about."

This segment aired on August 22, 2020.