Advertisement

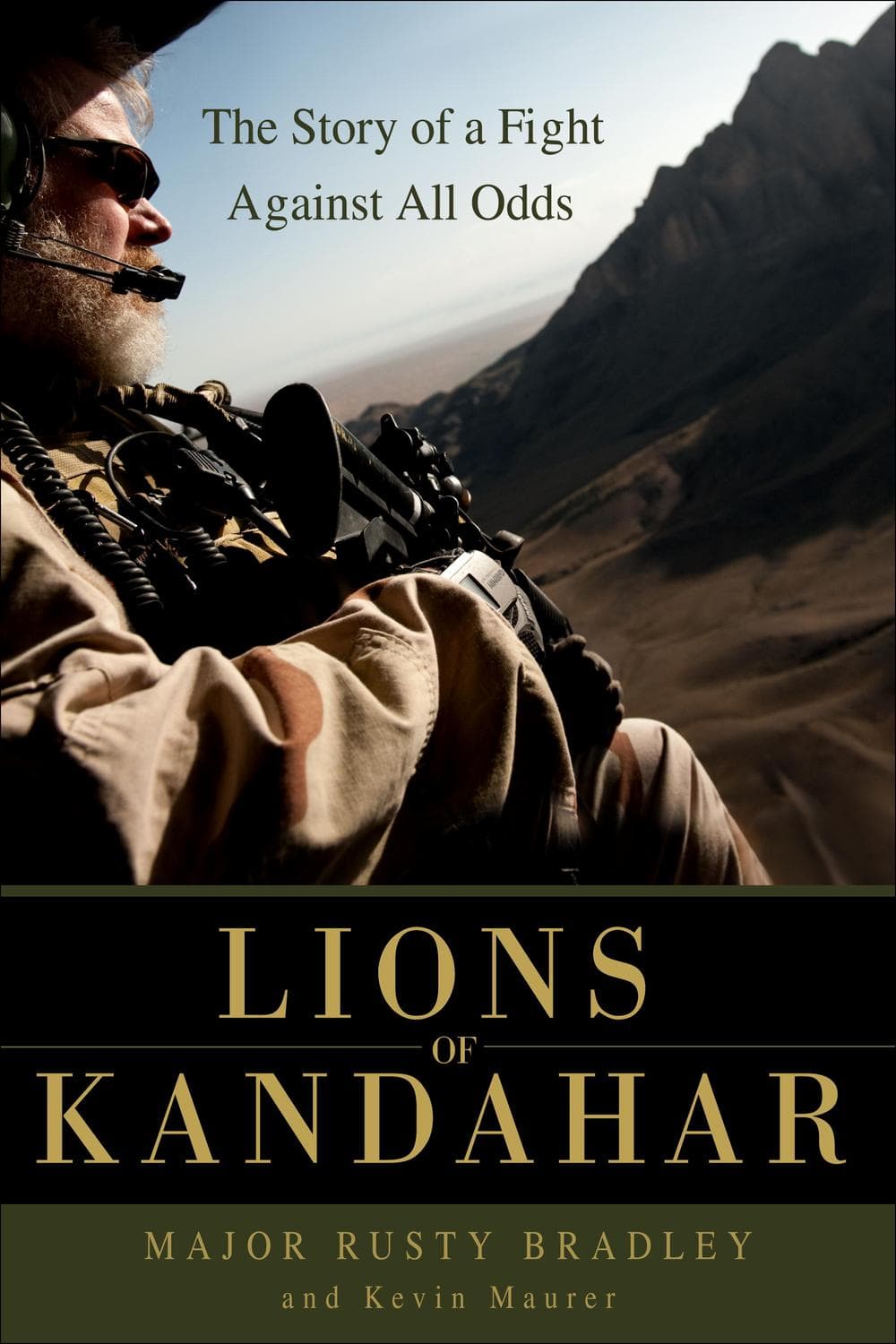

Lions Of Kandahar: A Fight Against All Odds

ResumeTom Gjelten in for Tom Ashbook

Inside the battle for Kandahar province, we'll be speaking with a Green Beret.

American soldiers have been fighting in Afghanistan now for nearly ten years, some of them over and over again.

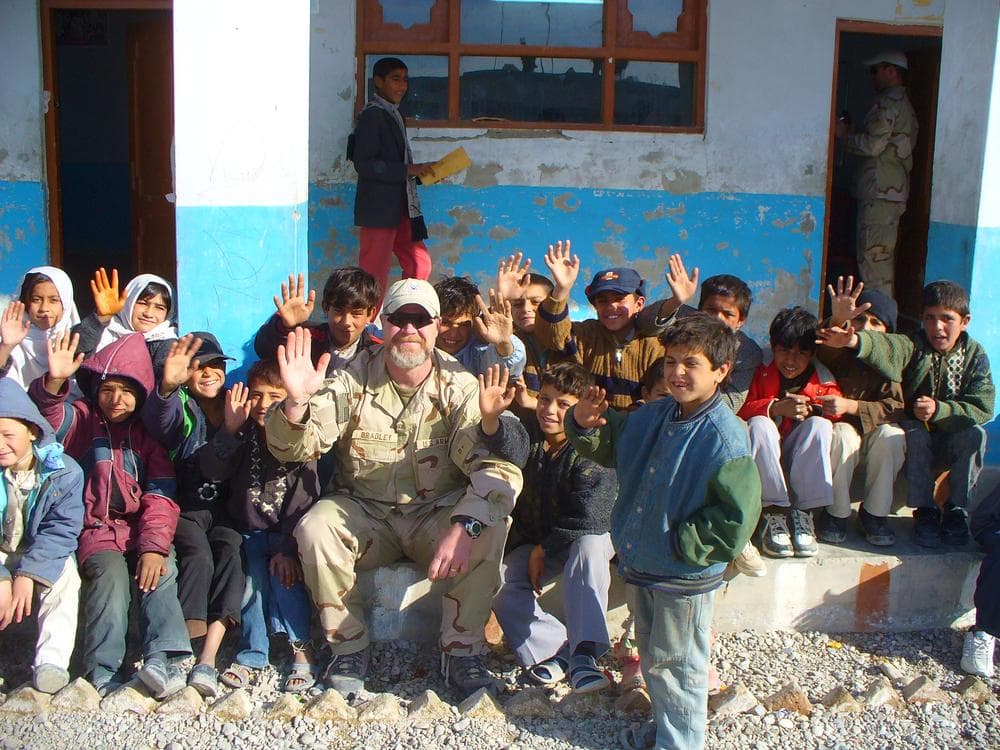

U.S. Army Major Rusty Bradley is just back from his fifth deployment there. And his assignments have been tough. At the very heart of the war effort.

Major Bradley is an Army Special Forces officer. These are the units that not only fight on their own but train Afghan soldiers to fight. Major Bradley is still on active duty, but he's written a book on his front-line experience in Afghanistan, the war we're trying to finish.

This hour On Point: "Lions of Kandahar."

-Tom Gjelten

Guest:

Rusty Bradley, a major in the U.S. Army's Special Forces and the author of "Lions for Kandahar: The Story of a Fight Against All Odds."

Excerpt:

Lions of Kandahar

Chapter 13

BLACK ON AMMO

Nothing is as exhilarating in life as to be shot at with no result.

—WINSTON CHURCHILL

From a distance, the westward end of the Panjwayi Valley looked like Eden. The endless sea of sand slowly gave way to the lush vegetation that embraced the mud huts and compounds strewn throughout the fields and irrigation ditches. The jagged mountains surrounding the valley seemed to protect it from the outside world.

But as my eyes scanned east toward the river I saw the mirage melt away. Scars and wreckage from the battle stretched for miles. I could see gunfire tracers and flashes from rockets exploding. Buildings and vehicles smoldered in all directions. The Canadian task force clogged the radio with messages about how they continued to “consolidate and reorganize” under enemy fire. Victory was slipping away.

We had no choice but to occupy Sperwan Ghar. Without control of that ground, the Canadians could not advance and would be stopped. Losing this decisive battle would be catastrophic for the people of Kandahar, the coalition, and all of southern Afghanistan.

The wind felt hotter than usual as everyone loaded up. I checked the radios inside the gun truck and scanned the laminated notepads and quick reference sheets stuck to every available empty space below the windshield. Tucked neatly around my seat were ammunition bandoleers, smoke grenades, medical equipment, water, and signal flares. Ready, I grabbed my hand mike and called Kandahar.

“Eagle 10, this is Talon 31. We’re moving.”

The convoy of gun trucks tucked into a perfect V-shaped formation. The route took us down from our perch on the ridge-line and past some green pine trees that masked our approach to Regay, a small village in the valley between us and Sperwan Ghar. We’d been watching the villagers from up and down the valley flee for days, but the scene when we entered the village was still shocking.

The villagers hurried past us, packed on broken carts, tractors, donkeys, camels—anything that could move. Regay was the final stopping point for the caravans of refugees seeking water before their journey to safety in Kandahar city. Hundreds crowded around the well. Each villager gripped a bright yellow or lime green water jug. No one made eye contact with us. They knew who we were and who was waiting for us.

Some of our ANA soldiers in a Ford Ranger were flagged down by a man leaving Regay in a faded white Toyota Corolla sedan. He never stopped but pointed to the hill, said, “Mines,” and drove off. The warning was radioed up to us. “This just gets better and better,” Brian said.

The open desert faded into Ole Girl’s side mirror and the tactical nightmare of villages and compounds opened up like the mouth of an immense beast. I glanced down at the map. After Regay, we were headed straight for Sperwan Ghar.

As Hodge’s team passed Regay, we switched the formation from a broad V to a straight line or “Ranger file” of trucks to maneuver through the never-ending labyrinth of broken buildings, irrigation ditches, marijuana, cornfields, and grape vineyards. Centuries-old ashpsh khana, or grape-drying huts, which stood three or four stories tall, dotted the fields, perfect redoubts for snipers. I kept one eye on the huts and the other on the dust-covered display of the digital map. We were close to the point of no return, an imaginary decision point on that map.

My nerves spiked as we raced down the dirt track toward the first compound. There was too much vegetation and too much cover. It was harvesttime, a bad time to start any operation. The enemy could hide anywhere. Shooters could be ten feet inside any one of the fields and we’d never know it, until they started firing. Brian, as driver and senior communications sergeant, always rode “dirty,” meaning he had his shotgun out the open window, ready in case an enemy fighter popped up. In this case, it would likely come from behind the compound walls or out of the fields.

The radio finally squawked to life. Jared, our ground force commander, wanted a countdown to the marker. “Talon 30, this is Talon 31, two hundred meters, wait one,” I responded.

Just as I said it, I caught a glimpse of movement—a figure, half crouching, half standing, on top of the thick walls of a large grape-drying hut. Snatching my binoculars, I focused in on him. I knew in my gut that he shouldn’t be there. The jet black turban and dark brown clothing stood out in stark contrast to the biscuit-colored dry mud walls. The hair on the back of my neck rose. RPG! I prayed that I wouldn’t see the flash of a rocket-propelled grenade headed toward my truck.

“Contact front. Enemy at eleven o’clock, two hundred meters on top of the grape hut. Kill that motherfucker,” I called to Dave, my gunner on the .50-caliber machine gun mounted on the top of the truck. The World War II model machine gun—known as an M2, or “Ma Duce”—with modern optics is as lethal today as it was sixty years ago.

The words had barely gotten out when Dave confirmed the target. “Got it,” he said coolly, sighting in on the Taliban position. He cut loose with a long burst, riddling the grape hut. A four-foot flame belched out of the M2 barrel, marking its tremendous firepower. Dave continued to shoot as we got closer.

My heart was pounding and sweat dripped into my eyes—I knew we were driving into an ambush. I pulled my headset down from the visor and called the report in to Jared. “Talon 30, this is Talon 31. Enemy contact eleven o’clock. They are in the grape huts.”

It didn’t matter if the enemy scout on the grape hut reported our position now. The machine-gun blast definitively announced our presence. I wished I had a dip or even a piece of gum to calm my nerves. But that thought disappeared with the vapor trail from the first RPG.

I saw the first rounds of the battle smack off my windshield as a hail of rocket-propelled grenades and machine-gun bullets sliced into our trucks. After that, there was no shortage of fire or targets to shoot at. From the top of the hill and surrounding compounds, they could see us coming. The Taliban knew what we knew: that Sperwan Ghar was prime real estate and they owned it.

“All 31 elements, watch your sectors and stay tight,” I radioed to the convoy. “Gunners, stay low in the cupola.”

Enemy snipers target the machine gunners; if our big guns went down, the vehicles would be defenseless. My mind focused again on the scout. How many were with him? What weapons did they have? We definitely needed more firepower. We had M4 rifles, M240 machine guns, .50-caliber heavy machine guns, a sniper rifle, and the Goose, a Carl Gustav 84-mm recoilless rifle, but this was the kind of situation where a mini machine gun is priceless, and I wished I had at least three.

“Eagle 10, this is Talon 30. We are troops in contact. We have twenty to forty enemy one hundred meters northeast of our position and are receiving intense RPG, PKM, and small-arms fi re from numerous compounds,” I heard Jared radio to our headquarters at Kandahar Airfield. “Request immediate close air support.”

Within seconds the radio responded clear and loud. “Talon 30, this is Eagle 10, roger, we copy troops in contact. Stand by.” The wait lasted only a few moments, but it seemed like forever. Back at the tactical operations center dozens of men on radios and telephones would be scrambling to find us the help we needed. They would have to coordinate with the Canadians, who controlled all the aircraft for this operation.

“Talon 30, this is Eagle 10. We have emergency aircraft inbound to your target area. ETA twenty mikes [minutes].”

Twenty minutes from now this fight might be over, I thought. Neither Taliban fighters nor their ammunition were in short supply. Shouldering the smaller M240 machine gun mounted to the door on my side of the truck, I started firing at the muzzle flashes and fighters moving near the compounds surrounding the base of the hill.

The firing was heavy from the right side, and the Taliban fighters seemed to continue to maneuver from right to left. But now our heavy weapons began “talking” the way their operators had been trained. This meant that one machine gun would fire a short burst into an enemy position and would rotate with another machine gun doing the same thing, all rotating fi ring at the target until it was destroyed. This technique allowed us to destroy the enemy using maximum firepower and minimal ammo.

In response, the Taliban fighters unloaded airburst RPG rounds all over us—rigging the rockets to explode so that shrapnel rained down on us. The volleys were meant to take out the gunners and wound troops in the back of the trucks.

“We have fire coming from our six o’clock. I say again, we have fi re coming from our six o’clock,” my team sergeant, Bill, said over the radio as I shook off the effects of the RPG blasts.

“Move truck 3 and 4 to my left and into an L shape,” I barked back to him.

The whole fight was a giant chess match. By putting our trucks in an L shape, we had managed to keep the Taliban at bay on the left and rear and make room for the rest of the convoy to move forward.

Brian called “Set”—the command that the truck was going to move—and quickly turned the vehicle to face the compound. Now we had the engine block between us and the enemy. I had no sooner reloaded my next can of ammunition than Dave called for a reload for his .50-cal. He laid a fresh belt of ammunition in the gun just as an RPG exploded on the truck’s front bumper, throwing up a massive wave of dust and debris. My teeth hurt and I had the strong metallic taste of explosives in my mouth.

Damn, we need more firepower. “Where is the CAS?” I screamed to Ron, my Air Force JTAC, one of the most important members of the team. It was his job to call in air strikes and get us the close air support we needed. I could hear the rounds cracking around me as I took a quick look into the back of the truck. Ron was firing at fighters behind us. That was good and bad. He wasn’t injured, but he also wasn’t calling in air strikes on the Taliban fighters surrounding us.

This time Dave, Brian, and I all saw the source and unleashed our fi re into the tree line beside a compound directly in front of us. Almost as quickly as we started firing, it was returned from the compound—a mosque. We were being attacked from a mosque. According to the Geneva Convention, if the enemy engages you from a holy site, using it as a military position, it can be engaged.

Dave went to work on the enemy machine-gun positions firing from inside the mosque. I called for him to give me covering fire and I got out of the truck with an AT4 and a LAWS. The AT4 is a disposable light anti-tank round. The LAWS is the Light Anti-Armor Weapons System for destroying small trucks and fighting positions. Both were made to destroy armor, but they’d also work on buildings.

I fired the LAWS first at the building directly in front of us to get my bearing and range. I might as well have thrown a tennis ball for all the good it did. I heard the loud thwack of rounds pass around me and I ducked back into the truck before I could fire the AT4. When the firing broke, I hopped back out, sticking closer to my truck, and took aim at the compound in front of us. The firing procedure was second nature: Front and rear sights up. Three hundred meters distance, set. Pull safety pin. Check back blast. Safety off and fi re. BOOM. Solid impact. Dust and debris flew from the main entranceway and every window. Just as I slid back into the truck, Bill appeared in my doorway.

“How you doing up here, fellas?” Bill asked in his slow Texas drawl, despite the maelstrom of fire around him. I’ve had the pleasure of serving with several Texans, and they were all born fighters. It must be something in the water down there.

“I need a round count, things are too crazy on the radio,” he said. As team sergeant, Bill kept the guns running with plenty of ammunition. He went to take stock of our stores, and returned shortly. “Got bad news, Captain. We are amber on .50-cal,” he said. Amber meant we’d already shot half of our ammunition.

I told him to get some bigger guns going, but he was already a step ahead. Sean, an ETT, was breaking out the Goose. The 84-mm recoilless rifle, dubbed the Goose in honor of its original manufacturer, Carl Gustav Stads Gevärsfaktori, could shoot a high-velocity, high-explosive round the size of a football into the buildings. “We’re going to try the AT4 first,” he said.

It sounded good, but I told Bill to use the radio next time he wanted to talk with me. He was too valuable to be running around without cover. “I need you alive and not leaking,” I told him.

He disappeared just as I heard the sweet whomp, whomp of helicopter blades. The AH-64 Apaches had arrived.

“Okay, motherfuckers, now it’s really on!” screamed Dave at the top of his lungs.

I turned to Ron and he showed two fingers. Two aircraft. Jet fighters were also arriving on station, and Ron began to coordinate and identify targets.

Since the main effort for Operation Medusa was the Canadian task force across the river, we had to get permission from them to use the Apaches. At the time, the Canadians were not under attack, and they eventually released the helicopters to our control. The Canadian task force had also wanted to keep the jets we had requested, American A-10 ground attack fighters, in reserve, but they relented and released them as well. While Ron sorted through the A-10 mess, Jared identified targets for the Apaches droning above us, which were part of the ISAF Dutch contingent. At his direction, the gunships made runs on the heavily defended buildings in our path to drive out the occupants. But the Dutch pilots were nervous about shooting too close to us. They didn’t want to be blamed for friendly fi re.

“If you do not engage the targets we tell you, then we cannot use you,” Jared finally snapped, exasperated. “The enemy is within two hundred meters of our location and we need the fi re now.”

The first two 2.75-inch rockets from the Apaches slammed high into the grape house in front of us, collapsing its entire front. The sharp cracks of the explosions marked a good hit. As the dust cleared from the rocket blasts, Afghan Army soldiers to my right cut down the four or five Taliban fighters who came stumbling out of the building dazed and confused.

As I reached down to grab another box of ammunition, a red glow flashed across the hood of my truck. The RPG exploded just outside Brian’s window, showering the truck with shrapnel. Stunned momentarily, we were snapped back into focus by Jared’s voice on the radio. He was still trying to muster fire superiority to push up toward the hill. Then the TOC in Kandahar came back: “Talon 30, this is Eagle 10. Here is your situation: the enemy count is not dozens, but hundreds, maybe even a thousand. Do you copy, over?”

Excerpted from Lions of Kandahar by Major Rusty Bradley and Kevin Maurer. Copyright © 2011 by Major Rusty Bradley and Kevin Maurer. Excerpted by permission of Ballantine Bantam Dell, an imprint of the Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

This program aired on June 27, 2011.