Advertisement

Actor Hal Holbrook

ResumeCelebrated actor Hal Holbrook on a lifetime of playing his iconic alter ego Mark Twain.

Mark Twain caught something essential about America, and for more than half a century the great actor Hal Holbrook has caught something essential about Mark Twain. In his white suit, wild hair, and big mustache, he first performed his “Mark Twain Tonight” one man show in 1954. And he performed it again last week, in Opelika, Alabama, at age 86.

He’s performed Mark Twain, at this point, longer than Sam Clemens did. He owns the part and, in some way, it owns him.

This hour On Point: being Mark Twain. A conversation with acclaimed actor Hal Holbrook.

-Tom Ashbrook

Guests

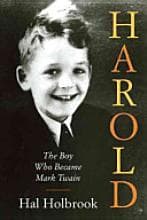

Hal Holbrook, acclaimed actor, known for his one-man show, Mark Twain Tonight! that he has performed since 1954. Winner of 5 prime-time Emmy Awards and nominated for an Oscar for his role in Into the Wild. Author of Harold: The Boy Who Became Mark Twain.

http://youtu.be/PNql_eRsWJo

http://youtu.be/_669ER2Gt34

Excerpt

I'm trying to remember being held by my mother. Those memories are all so dreamy now, as if none of them ever really happened. I could have dreamed my memories and they would be as real to me. I'm told she was just a young girl and that she left when I was two. I have a picture of her, a little brown-tinted photograph in a gold frame, and she is, indeed, a young girl with a shy smile. But there is some other message in her eyes. Something tired, the eyes of a girl who has had enough and wants it to be over.

All I have are two drifting memories of her. The first is on the enclosed porch in the big Cleveland house, green wicker furniture. A baby is stumbling around, knocking into the sharp stub ends of wicker and crying, and a young woman reaches for this baby, but Grandma moves in ahead of her and the baby never gets inside the young woman's arms. That would be me.

The other memory is a few years later, in the cigar-scented den off Grandpa's bedroom in the South Weymouth house when I was about six years old. My mother and father have come out of the blue to visit us. They are tap-dancing in the archway of Grandpa's den and she is smiling, but there is no beginning or ending to this memory. It is just a vision, connected to nothing, two young people dancing in limbo. I revisited that house many years later because I was told the people who live there now had sometimes seen the ghost of a young woman with blond hair when they went down into the basement. They were very matter-of-fact about it. They told me I wouldn't feel afraid of her, because she was not threatening. They had a young son, and he agreed. She was friendly, he said.

When I descended, I told myself that I would like to see her, that if I could believe in this apparition, I would know my mother. The basement was larger than I had remembered, much larger, so clean and dry, the paint so fresh and shiny after all these years. It stretched away around a corner to the right, where the laundry and shop tools were. To the left was the coal room for the furnace, with the coal chute slanting down into it. It gave me a shock of remembrance, the glistening chute. I remembered crouching there as a little boy. They said she would be in this part of the cellar. That I would probably see her here. I waited. I made myself still, my heart and my body. Did I feel a presence? Was someone there? I wanted her to appear.

"Mother?"

In my heart I felt a tiny shock. Was it her I felt? Or was it the word I don't remember ever saying that sent a thrill through me?

"Hello, Mother. It's me, Harold."

I hung on to the feeling as long as I could but finally had to let it go. I don't believe in ghosts. Maybe that had something to do with it, maybe not. I don't know.

I would never see her again after she and my father suddenly appeared and danced in the archway of Grandpa's den. Nowadays, at night when I turn out the lights in the living room before going up to bed, I look at her little picture in the gold frame under the lamp where my dear wife has placed it, and I say, "Good night, little girl." She was just a little girl, that's all she was, those years ago when last I saw her.

My name is Harold. The year after my mother disappeared for good, they sent me away to boarding school to make a man of me. I was seven years old. The junior school was run by the Headmaster, a short, round man who told stories about a turtle that lived under a rock beside the path to the dining hall. That was his good side.

One afternoon I was playing halfback in football practice and I got a shoe full of cleats in the face. Baam! I started to cry. The coach banished me for not being tough enough. I was already in disgrace from the Saturday before, when I caught a pass and ran eighty-eight yards for a touchdown. I couldn't understand why no one was chasing me, until they told me I'd gone the wrong way.

I was ashamed. I decided to run a mile. I'd never done it before. Across from the football field was a cinder track--five times around for a mile. I hobbled over there, pulled off my helmet, and drew a line in the cinders. Five times around. No stopping. My football shoes and shoulder pads were pretty heavy, but I didn't think about that right away. Soon I was gulping the fall air of Connecticut and it bit down into my lungs like slivers of ice. By the end of one lap the shoes felt like hunks of pig iron and the shoulder pads were flopping around, banging my ears.

"Please, God, don't let me fail! Maybe the Headmaster is watching me up on the hill, from the window in his office, where he likes to punish us. Maybe he will be proud of me if I keep going all the way."

Five laps. Now only three and a half. I was beginning to cough up stuff and my lungs were filling up with the ice slivers. Maybe the coach was watching me, too, and he would think, "That Harold has guts, after all. Look at him go." I began to think I was going to make it. A sensation of air spread through my chest, and it seemed to me I could even breathe better. The far turn was coming up again, where those big fall leaves were letting go, and then came the homestretch and I had run four laps. Or was it three? Maybe it was only three. I didn't want to cheat. I could say four, but if it was only three, that would be cheating. They're probably watching me anyway. If I can really make it to a mile without stopping, that will be something big. Very big. My legs were beginning to feel as if they were attached to swivels, and I couldn't see anything past the sweat in my eyes. There was no sound outside my head except the awful gasping that erupted from somewhere in my chest. I yearned to walk a few steps. Just a few. No cheating! Gotta keep moving or it's not running the mile, it's walking it. It's being weak. There's that far turn again, with the harsh smell of brittle autumn leaves. If I can just keep moving until I see that line in the cinders, I will have run the mile.

I stopped. There was a great thumping sound in my ears and my eyes were stung shut from the sweat, but I had done it. I had run the mile. It got quiet and I rubbed at my eyes, and when I looked around, I was alone. The football field was empty. Away up the hill I could see the last of the team rounding the corner of the white junior school building, and I could imagine them disappearing into the darkness of the basement, where the Headmaster would be waiting. I would be late.

The hill was going to be tough. In winter we built a ski jump on it out of wet snow, so it was steep. There were cement steps along the left side of the hill, under the three big maple trees we climbed when we were playing Tarzan of the Apes. I could go up the steps. But cutting across the slope of the hill was more direct, and that's where I was already heading. Breathe! Lean forward into the hill so you don't fall and roll down it. Maybe the Headmaster won't be waiting in the basement today.

It must be adrenaline that keeps you going when you want to stop. Adrenaline or something. I made the hill, and I made the corner of the wooden building where we slept and went to school all year long except for vacations at Thanksgiving and Christmas. And there were the steps, three of them, down into the big, dark space you had to cross before you entered the locker room. And he was there in the dark. Coming out of sunlight into the darkness blinded me, so I couldn't see him. All I heard was a voice.

"Holbrook, you're late." The Headmaster was using my last name, not Harold.

"Yes, sir. I'm sorry ..."

"Come here."

"Sir, I was running a mile ..." Whack! Whack! His hand flew out like a whip and lashed the right side of my face and then the left in one smooth, beautiful move. Perfect aim. I tried to get by him toward the locker-room door, but he caught me and drove his knee between my legs. I saw stars. The blow pitched me toward the whitewashed wall of the locker room with all those black hooks on it, and I saw that my head was going to land right between two of them. Clunk!

"Get showered."

I must have closed my eyes. When I opened them, he was gone. I heard a sob fly out of me and the tears came quick and hot. "If Grandpa knew what you did to me, he would come down from South Weymouth and kill you, kick you, murder you, beat you until the blood spurted out of your nose and ears. You would be dead!" Grandpa would be wearing his big overcoat with the smell of cigar smoke in it and he would pat me on the head and say, "Don't cry, Buddy, we're going home." Then we would walk away and leave the Headmaster dead on the ground.

I was not going into that locker room with my eyes red. I was going to let the pink go away first and get my breathing right. Maybe I was only seven, but I was not a sissy. I was not going to walk into that locker room crying, even if my name was Harold.

The mind flows back. We enter memory, and events and people pour out like little swaying creatures, saying, "Here I am, here I am." The plot is there, the road your life has taken, and those little creatures appear faint and whimsical because you've traveled so far from them. But some of these creatures--certain crippled ones--do not speak out to you. They limp gravely across the past with hard, dead eyes and they stare at you with a question: What do you think of me now?

The Headmaster is a crippled figure. After seventy-six years I cannot love him. Something having to do with the awful sorrow of life has helped me forgive other people, and that helps me to forgive myself. But I haven't been able to forgive him.

I can see him sitting behind the yellow oak desk in the large classroom after the last class of the day, sitting on a platform slightly above us. It gave his dwarfed height a stature in front of the room full of young boys who waited. We assembled in that classroom before going out to the playing fields, and we waited for our name to be called out. It meant we were going to be punished. The Headmaster enjoyed this ritual. He played his role like a cat, staring at us for the longest time without blinking. His pale blue eyes and round face were almost expressionless, but not quite. Something was there, a faint emotion. Sometimes it suggested a hint of friendship. Maybe today he wouldn't call out names, he'd tell a little story and we would laugh and feel relief and gratitude. He liked telling little stories. Then he called out a name."Holbrook."

He didn't say the name harshly. It was more like the sound of someone who wanted to share something nice with you. A friendly thing. It meant you had to line up outside his office and be punished. He never told you why.

When you entered his office, he would move about quietly in a familiar way. He was not an imposing figure. He was short and rotund and balding, and perhaps he thought of himself as benevolent, a twin version of the mother and father you didn't have.

"You know what to do, Harold. Take down your pants." You unbuckled your pants and let them fall.

"Both of them." You pulled down your underpants.

"Assume the position."

You took hold of the arms of a chair that had been neatly placed for you and bent over. Meanwhile, he would be searching in the closet for something. It was a one-by-three flat stick from a packing crate, about three feet long. Probably pine. You waited while he got this stick and then you held your breath while he moved across the room toward you. Whack! Whack! Whack! Three. Whack! Four. Whack! Five. You tried not to cry out, because the boys waiting outside would hear that. Whack! Six. If you cried, he'd stop, but--Whack ! Seven. Am I bleeding? Maybe he'll stop if I cry--Whack! Eight. A sob. Whack! Nine. Tears. Tears. Crying. It's over. He just wanted the sound of crying.

"All right, Harold. You can go now. Pull up your pants."

Once, when I came out of the room, humiliation blinding me, the piano teacher was waiting down the hall past the line of boys. I'd forgotten about our lesson, and there she was in a doorway, searching my face with her eyes as I got close. Brown eyes, pools of softness. I could tell she had listened to my punishment. She held the door for me, and while I walked over to the piano and sat on the bench, she closed it. Then she sat beside me on a chair pulled up close. There was a pause, an emotional one, while she waited for me to balance myself on the brink of breaking down. I had been learning to play "America" two-handed, and I placed my hands on the keys and tried to remember the first note. Then I started to cry. The piano teacher put her arms around me and held me to her. It was an act of kindness I have remembered all of my life.

Excerpted from HAROLD: THE BOY WHO BECAME MARK TWAIN by Hal Holbrook, published in September, 2011 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2011 by Hal Holbrook. All rights reserved.

This program aired on September 21, 2011.